Actual investing – Active Share and Low Turnover

Today’s post is a look at a report from Baillie Gifford on Actual Investing, which is their spin on active share.

Contents

Backdrop

The timing of the report is (in my opinion) is driven by two things:

- The rising power of passive index funds and ETFs, and the qualms expressed about this power by leading proponents of such funds, including Jack Bogle and Burton Malkiel.

- A recent study on the distribution of stock returns, which appears to give active managers ammunition with which to fight back against the passive indexers.

So before we look at the BG report, we need to double back to a post I wrote a few weeks ago about the Bessembinder report.

Bessembinder

Professor Hendrik Bessembinder, of the WP Carey School of Business at Arizona State University looked at stock returns in the US from 1926 to 2015.

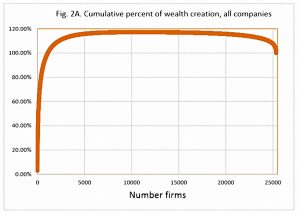

He looked at the returns on 25,782 listed stocks.

- Only 42% of these had a better return than “cash”.

Most stocks do not outperform Treasury bills over their lives.

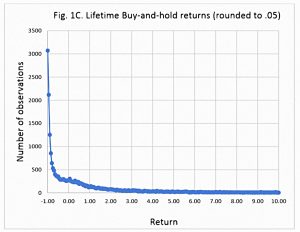

The average stock was listed for just seven years, and the most common lifetime return was a loss of 100%.

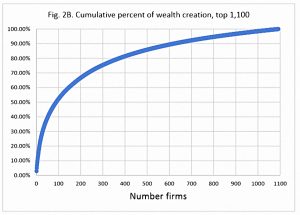

The finding that the industry has picked up on was that just 4% of listed stocks were responsible for all of the positive gains of stocks during the period.

- Half of the growth was down to 0.4% of stocks (just 86 firms).

Bessembinder found that a greater proportion of large stocks had better returns than cash.

- A major exchange (NYSE) and a lack of debt were also positive factors.

He also found that stocks are becoming less and less likely to be winners.

So should we all become stock-pickers? The rewards are good, if you can pick reliably:

The returns to active stock selection can be very large. Of course, the key question of whether an investor can reliably identify such “home run” stocks, or can identify a manager with the skill to do so, remains.

Active managers

As I said last time, over the summer I’ve seen three presentations from active fund managers who explicitly referenced Bessembinder.

The first and most vocal of these was James Anderson, manager of the wildly successful Scottish Mortgage Trust (SMT).

- SMT is of course part of the BG stable.

Anderson is understandably keen to attribute the success of the trust to his stock-picking abilities rather than the stellar run of US tech stocks that he is over-exposed to.

Your returns are dominated by a very small number of companies and it’s trying to identify which ones have the possibility of greatness that matters.

You can still be quite diversified and not capture any of these stocks.

Anderson’s story is that “it’s different this time” – we’re entering a period of “even more profound and rapid change” than before, and the benefits will accrue to a very small set of firms.

- So these are the ones to buy, regardless of their current price.

Anderson says that the Bessembinder’s winners were:

- Early entrants to markets that later became huge.

- Founder-run.

- Willing to accept / embrace uncertainty.

The first two points are hard to argue with, other than that there are a lot of founder-run early movers who fail, and it’s hard to identify winners in advance.

- Quantifying the third point is just hard full stop.

7C response

I agree with a lot of what Anderson says:

- The dominance of the major platforms could increase from here.

- And regulation could help, since incumbents have deeper pockets from which to fund compliance.

But everything has a price, and we may already be paying too much.

- Growth doesn’t work in aggregate because eventually someone pays too much for it.

There are three ways in which to react to Bessembinder’s finding:

- The Anderson route – work out (guess) which characteristics will lead to future success, and buy a lot of that kind of thing.

- This is risky, but could produce exceptional short-term results.

- Make sure that you are well-diversified – buy the index trackers.

- Identify the characteristics of stocks that underperform, and avoid them.

- If 4% of the market has all the returns, then the bottom 96% is flat.

- But leave out the bottom 58% (the ones that Bessembinder found did worse than cash), and you’re going to do pretty well.

- Stock screeners can help here, and so can factors / smart beta.

I advocate a combination of the second and third approaches.

Actual investing

Now on to the new report.

- It’s by Stuart Dunbar, who is a partner at BG.

He begins by harking back to the nineteenth century:

The investment industry concerned itself with actual companies and actual projects.

Nowadays though our industry is obsessed by abstract concepts – such as regional allocations, sector positions and factor weights – which have little to do with our real purpose.

Hmmm. At least Stuart supplies a definition:

The fundamental purpose of investing is to use available capital from those who have surplus to fund the ideas and projects of entrepreneurs and company managers who see an opportunity to generate profits.

Our job as professional investors is to weigh up the risks associated with those ideas and projects, the range of possible outcomes and their probabilities, and thereby put a price on the equity or debt that is being used as funding.

I would argue that for private investor, the fundamental objective is to preserve – and ideally increase – purchasing power.

- There will be projects behind this, obviously, but for investors the projects are the means not the ends.

Stuart doesn’t see passive investing as real investing, and thinks that much of “active” management is:

Simply second-order trading of existing assets, with the main focus being to try to anticipate the behaviour of other investors.

Which is not real investing either.

- This sounds like he’s getting at short-termism and traders, rather than the closet indexers that I assumed would be his targets.

I agree with Stuart that pointless churning of assets is only good for those on commission, but not all trading is pointless.

- But I’m not convinced that trading simply creates volatility.

Isn’t another word for this process price discovery?

Flows

Over the eight years to 2017, passive investment strategies have seen nearly $1 trillion of net inflows. Traditional active strategies have seen outflows of over $600 billion.

We know who’s winning, then.

Costs

Little wonder that costs now dominate the narrative rather than value for money.

I would say that costs are bound to dominate when expected returns are low, and costs will therefore greatly impact returns.

- When active investors underperform as a group (as they must) then high costs are a hard sell.

The real issue is that active funds charge too much.

- And while charges are linked to assets under management, the industry will focus more on marketing than on competence.

- They said as much at the Boring Money Conference earlier this year.

CAPM

Stuart lays the blame at the door of CAPM.

- But the index funds didn’t arrive for a decade or more, and they weren’t popular at first.

So there must be more to it than that.

- Perhaps we’re back once more to the fact that active funds charge more, yet underperform.

Closet indexing

Many feel driven to hug benchmarks so as not to stand out from the crowd, and to focus more on marketing than on achieving good results.

Being predictably average is [seen as] more attractive than being unpredictably outstanding.

No argument from me here.

Short-termism

A huge number of companies pander to market short-termism by manipulating their own cash flows to hit short-term targets and pay out dividends or buy back shares, in the process foregoing profitable investment opportunities but handily hitting earnings targets that secure executives’ bonuses.

This is another point that is half-true:

- It’s hard to deny that executives are self-serving.

But buybacks work (those firms outperform) and “profitable investment opportunities” are hard to find when interest rates are so low that capital is virtually free.

- There’s also an argument that the network effects enjoyed by the big tech winners mean that the R&D / capex to payout ratio was always going to fall.

Bessembinder #2

Stuart brings up Bessembinder next.

So much for CAPM – the truth could not be further from the normal distribution which underpins it.

He’s got a point here, but the conclusion he draws is the same as his BG colleague James Anderson:

Clearly, if you find the right stocks, you will outperform the market and capture a huge amount of the total creation of wealth.

On the other hand, missing out on those stocks will result in horrible underperformance.

Well, not necessarily.

- And indexing would be a safer way of making sure you include the winners.

Most bottom-up stock-pickers would claim an ability at identifying such winners.

Of course they would, but where’s the evidence?

Turnover

Stuart pushes on to research from Petajisto and by Cremers and Pareek which suggests that the right approach to active investment is a combination of:

- High active share

- Low portfolio turnover

Managers with high active share and low turnover on average outperformed market cap weighted indices between 1995 and 2013 by 2.3% pa net of costs.

This is good intelligence, but Stuart turns it into a pitch that we should “pick the right firm”.

- In other words, we should look at philosophy rather than historic performance, where “by definition the good are mixed with the lucky”.

That works if you are employed by BG, but I plan to stick with the numbers.

Conclusions

When I saw the report I thought it was more evidence that active managers had got hold of the wrong end of Bessembinder’s stick.

- But perhaps it’s just the BG stable.

In any case the combination of active share and low turnover was new to me.

- I plan to investigate both topics (and their combination) further, and will return in due course with another post or two.

Until next time.