Strategic Rebalancing

Today’s post looks at a recent paper from MAN AHL about strategic rebalancing.

Rebalancing

We looked at rebalancing a couple of years ago, as part of our Money Deck series.

- Let’s start by summarising what we said then.

Rebalancing is the process of re-aligning the asset allocation within your portfolio when it drifts from your ideal allocation.

- This will happen naturally as different investments grow at different rates (or even shrink).

In a (too) simple 60/40 stock / bond portfolio, equities will usually gain more than bonds.

- At the end of each year, you would would sell some of your equities and convert them into bonds to get back to your target allocation.

Rebalancing works best with portfolios that include more asset classes.

- Rebalancing is also best done within tax-sheltered accounts (here in the UK, within SIPPs and ISAs) since selling investments in taxable accounts can trigger a tax bill.

Rebalancing is proven to be beneficial, but it is psychologically difficult to implement, because you need to sell your winners, and buy your losers.

In a passive portfolio, not trading in between rebalancing cycles will help to minimise trading costs.

- As well as saving money, rebalancing reduces risk.

In general, the assets which produce the greatest returns are also those with the highest volatility.

- Left alone, a portfolio will become ever more heavily loaded with these risky assets.

Avoiding drawdowns is achieved through a form of automatic market timing.

- Each time you rebalance, you are selling an asset that has increased in value, and buying an asset that hasn’t increased so much (or has fallen in price).

Reversion to the mean suggests that sooner or later, prices will return to their averages.

- After a period of above-average returns are higher than this, it’s natural to expect a period when they will be lower.

- The opposite applies after a period where gains have been small or negative – good times can be expected in the future.

In rebalancing, you have sold something that is likely to do less well in the future and bought something that is more likely to do well.

- This is anti-cyclical, or contrarian investing.

Done slowly (to avoid the shorter-term momentum effect), rebalancing has been shown to add more than 1% pa to returns from globally diversified portfolios.

The simplest way to re-balance is to take advantage of the natural flows of money into (or out of) your pension pot.

- If you’re still in the accumulation phase then rebalancing is easy – you just add the new money to the underweight assets.

- If you’re already retired, then you can just do the opposite – sell the investments that you have too much of to generate cash to live on.

These approaches are known as time-bounded, calendar and cash-flow rebalancing.

- Strictly, calendar rebalancing applies to static portfolios (with no cash flows).

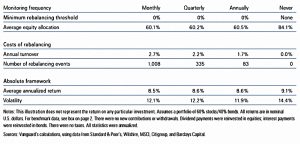

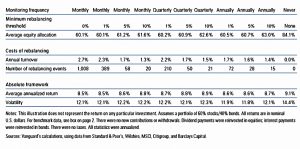

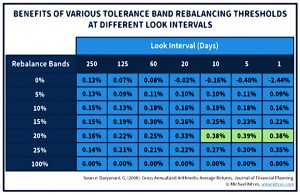

- Intervals of 18 months have been shown to deliver most of the benefits of rebalancing.

The problem with cash flow rebalancing is that it’s too frequent.

- In decumulation it will be at best annual, and in accumulation it’s likely to occur after each monthly paycheck.

Luckily, the sums of money involved will be small relative to the size of the portfolio (except in the very earliest years of investing) and the negative effects will be outweighed by progress towards longer-term goals.

- As always, try to minimise transaction costs and be tax-efficient.

The alternative approach is threshold rebalancing.

- This is also known as inertia or tolerance band rebalancing.

You only re-balance when the misalignment of your portfolio reaches a trigger value (say an asset is out of whack by 5%).

- The potential advantage is that in a steady market you might not need to rebalance for years.

- You also stand a better chance of choosing the best “buy low and sell high” moments.

The higher you set your threshold, the more potential you have to take advantage of momentum effects, but you are also potentially taking on more risk at the same time.

Work by Stein and DeMuth suggests that the best threshold is 20% of the allocation to an asset (though others like Vanguard suggest bands as narrow as 5%).

- In our 60 / 40 example, this would mean rebalancing when equities reached 72% (or fell to 48%).

- Or when bonds fell to 32% – for multi-asset portfolios the smaller allocations will drive rebalancing.

Threshold rebalancing is an attractive idea, but most people will be either adding money to, or taking money from their pension pot.

- Or they may have dividends to reinvest.

And there’s the closer monitoring of portfolio drift to consider.

- But you could combine a cash flow approach with a threshold approach, allowing either event to trigger rebalancing.

The key point is to avoid rebalancing too frequently.

New articles

Over the subsequent two years, I’ve read several further articles about rebalancing.

It Can Be Easily Done (ICBED) reported that the optimal balancing period can be as long as four years, depending on market conditions.

- The key point is to make sure it’s no more frequent than annually, so that you don’t throw away momentum gains.

ICBED uses a momentum calculation (in his case, a variation on absolute momentum) to double check whether he should implement a rebalance that is due.

- I do something similar myself, by always checking a chart full of technical indicators before placing a rebalancing trade.

Michael Kitces wrote about a 2007 study from Gobind Daryanani using data from 1992 to 200, and a 5 asset portfolio of large‐cap US, small‐cap US, REITs, commodities, and bonds.

- Daryanani found that 20% thresholds which were monitored at least every two weeks produced the best results.

- Of course, most of the times you look, there will be no rebalancing trades to be made.

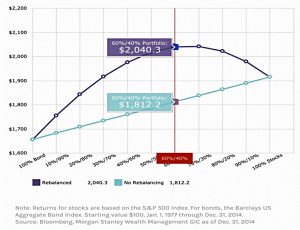

Cullen Roche at Pragmatic Capitalism pointed out that rebalancing only works in risk-adjusted terms.

- You sell the excess portion of the higher risk asset which reduces your risk, but also impacts your absolute returns.

This is particularly useful for those of us who are at our prescribed limit of risk assets, but I don’t meet many people like that.

- I’m overweight property, bonds and cash, but underweight stocks

- So selling “excess” stocks isn’t a priority (and indeed, my rebalancing system wouldn’t tell me to do that).

Note also that the benefits of rebalancing tail off as your equity allocation increases.

- You can’t beat a 100% stock portfolio, if you are prepared to stick with it.

As Cullen says:

You don’t rebalance to beat the market. You rebalance to ensure you don’t get scared out of the market.

The suboptimal strategy that you stick with is better than the optimal strategy that you bail on.

He calls this behavioural alpha, but it’s important to remember that having the correct asset allocation won’t protect you at the times when you are most likely to be scared out of the market.

- Many diversification benefits disappear during a crash, as correlations increase.

Cullen himself favours a more active strategy called countercyclical indexing.

On Alpha Architect, Jon Seed looked at rebalancing in the context of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM).

CAPM [doesn’t] advocate allocating more to stocks just because the market went down. Rebalancing should only occur when an individual’s tolerance for risk changes.

Prices typically drop heading into a recession when fewer investors can tolerate extra risk. If an investor is not scared, worried about their job, or light on other assets, then she should theoretically rebalance by adding equities after a market correction.

Jon concludes that rebalancing is fine during accumulation, but needs to be approached cautiously in decumulation.

- He recommends trend following as an insurance to limit losses and avoid the “uncle point” (where you give in and sell stocks in a bear market).

A cash buffer can provide similar “sleep at night” security.

Corey Hoffstein at Newfound Research has shown that the month in which you rebalance seems to matter.

- Rebalancing in May does much better than rebalancing in October, presumably because of the seasonal affect in equities.

- You would be selling stocks after their winter rise.

This won’t be a massive problem for most investors, who are likely to rebalance after an annual portfolio review at the start of the calendar year.

- But it might be worth delaying equity sales for a few additional months.

MAN strategic rebalancing

And so, after one of my longest ever preambles, we come to the recent MAN AHL paper.

- It’s an elaboration of the point made by ICBED that rebalancing too often cuts off momentum gains.

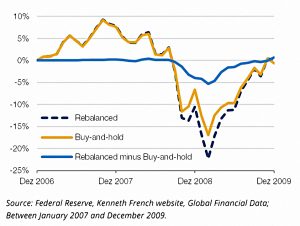

MAN point out that in trending markets, rebalancing can lead to larger drawdowns than buy-and-hold.

- These drawdowns can be mitigated by allocating some money to a trend-following strategy (as I do).

In geek speak, rebalancing is adding a short straddle (selling a call and a put option) on relative asset values, which leads to negative convexity.

- Trend-following is like a long straddle, with positive convexity.

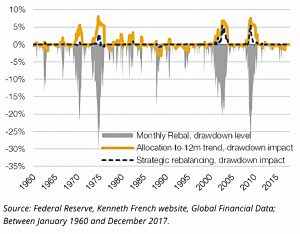

MAN found that allocating 10% of a portfolio to trend-following reduced drawdowns by 5% from 1960-2017.

Strategic rebalancing uses the signals from a trend-following model to time the rebalancing.

- If equity markets are in a downtrend, rebalancing is delayed.

- But there is no direct allocation to trend following.

This is similar to ICBED’s use of absolute momentum – and my use of charts – in rebalancing.

Conclusions

Rebalancing is a good idea in theory, and a bit of a no-brainer when applied to natural portfolio cash flows.

But in a static portfolio, you need to be careful:

- Are you above your target allocation to stocks?

- Few people are, when they take their total wealth into consideration.

- Are stocks in a downtrend?

- If so, don’t sell any.

- Not selling in a bear market is more important than rebalancing.

- Don’t rebalance too frequently, or you’ll miss out on short-term, momentum gains.

- Annually is the highest acceptable frequency (unless you are using threshold rebalancing).

- But a longer gap could work even better.

- Try to rebalance as close to May, and as far away from October, as is practical.

Aside from rebalancing, consider an allocation to trend-following to reduce drawdowns without impacting returns.

Until next time.