Sushil – Apostate Economist

Today’s post is a profile of Guru investor Sushil, who appears in Guy Thomas’s book Free Capital. His chapter is called Apostate Economist.

This article is part of our ‘Guru’ series – investor profiles of those who have succeeded in the markets, with takeaways for the private investor in the UK.

You can find the rest of the series here.

Contents

Sushil – Apostate Economist

Sushil is one of the anonymous investors in Guy Thomas’ book Free Capital.

After grammar school in Birmingham, Sunil studied economics at university, and then did a PhD in econometrics. He then joined a business economics consulting firm as a trainee.

- His then disability discouraged him and he realised at age 26 that making money from investment could mean independence.

He started trading with £5K in 1992, soon after the `Black Wednesday’ exit from the ERM, alongside lecturing in a business school.

- He became a full-time investor at 35.

Sushil lives and works from two adjacent modern houses on the edge of a commuter town in Berkshire.

- At the time of the interview, he had six flat-screen monitors on his desk, though in practice he often sits on a day-bed, as a result of a lot of (largely successful) orthopaedic surgery.

Trading performance

Sushil describes the early years as “two steps forward, one step back.”

The trend was slowly upwards, but my net worth was subject to large swings, and there were often overdrafts or credit card debt. A lot of the time I felt ashamed.

Before the internet, private investors had little access to information.

- Sushil picked the Evening Standard from the bin at the railway station to get end of day prices.

During the 18 months of the dot com boom, Sushil’s portfolio increased more than ten-fold, and he held on to most of the gains.

- He realised that an unjustifiable bubble in tech shares from the middle of 1999, but felt that riding the bubble was rational.

- He gradually re-invested away from the technology sector from that point, without ever calling the top of the market.

In a decade from the mid-90s he multiplied his (over-concentrated) portfolio by 30 times (around 40% pa), and was able to quit his job as an academic.

- He tried some home-based economics consulting, but after 18 months this work died way and he was left with investing.

A little later, some friends from university formed a fund to co-invest in some of his ideas.

- He won’t take on any more investors.

In the eight years to April 2010, Sushil outperformed the FTSE All-Small Total Return Index by around 10% pa.

- In his ISA (with no tax to pay), outperformance was 15% pa over the six years to April 2010.

- Note that small companies lagged over this period, so outperformance of the FTSE-100 Total Return Index was only around 9% pa.

# Liquidity

Sushil now manages more than £10M, and liquidity has become an issue.

- Larger investors like Sushil need to buy and sell over a much wider range of prices than normal private investors.

When I buy a share, I want the next move to be down, because I hope to buy more. And when I sell, I want the next move to be up, because I have more to sell.

He now holds around 60 stocks, up from less than ten a decade ago, but mostly for reasons of liquidity.

- Almost half the portfolio is in his six largest holdings.

Investment strategy

Sushil is no fan of diversification:

I want a portfolio with large idiosyncratic risks, provided they are mis-priced.

This is the Buffett approach.

I have no strategy, and I am suspicious of all theories. I try to be flexible and use my common sense.

In practice, he uses three systems:

- buying a perpetual stream of income cheaply

- “the value approach”

- buying in anticipation of a change in market perception

- “the Keynesian beauty contest”

- buying in anticipation of what he calls a “knowable change in state”.

He has a focus on this “knowability”:

Focus on things where research can plausibly give you superior insight - the microeconomic advantages of a particular company. Ignore things which are not knowable, general macroeconomic predictions.

He concentrates on small companies, or situations where a seller is motivated by factors such as his tax situation or an urgent need to raise funds.

- He often takes large stakes (above the publicly declarable minimum of 3%) in small companies, sometime several at a time.

I am always conscious that when I trade, I think I have superior information, but there is also a counterparty who thinks he does. It is not plausible that I will on average be better informed than the dozens of analysts looking at any large company.

He thinks that the concept of expert advice is generally overrated in investment.

A consensus of expert opinion is not useful, because it’s already discounted by current market prices.

He thinks successful investors have “a psychological predilection towards figuring things out for themselves.

He doesn’t use most of his quantitative skills:

You need to be able to add, subtract, multiply, divide, and you need to understand leverage and compounding.

The most interesting situations are often where only qualitative information suggests favourable prospects. Quantitative people shy away from these. That leaves more opportunity for those who can act on qualitative information.

Tax

Sushil ignores the usual advice of “The tax tail should not wag the investment dog.”

- He always thinks on a post-tax basis.

Tax is one of the few aspects with some certainty and stability which you can do something about.

With ISAs, SIPPs and spread betting, the UK is quite a low-tax jurisdiction for investors.

Sushil uses spread betting sparingly, and mostly for shorting, which he admits is difficult.

- He also uses spreads to hedge up to 30% of his portfolio via FTSE100 futures.

Markets tend to go up over time. And a short sale which is going wrong is an increasing problem.

Leverage

Sushil doesn’t like the high leverage of spread betting, being a fan of Kelly betting theory.

Apart from your own mistakes, lenders can reduce or cancel the facility at the worst possible times. Leverage beyond a low level is almost always a bad idea.

I already have more than enough money. Why should I take the risk? I find it incredible when I read of people who already have millions getting into difficulties.

Low leverage is also psychologically helpful:

When the market has fallen 40%, you want to be at your boldest. That is psychologically difficult when you have lost 40%. It is psychologically impossible if you have lost 80%.

Kelly betting

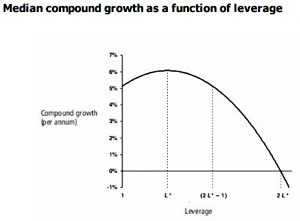

The theory of optimal compound growth – from John Kelly and Ed Thorp – says that investors are better off maximising expected logarithmic return, not expected return.

- This in turn implies lower leverage than you would think.

An investment which either rises 25% or falls 20% with equal probability in a period has a positive expected return of 2.5%, but an expected logarithmic return of zero.

- Leveraged by 2x, it will rise 50% or fall 40%.

This leverage increases the expected return to 5%, but reduces the expected logarithmic return to less than zero (-5.27%).

- The negative expected logarithmic return means that the leveraged investor will almost surely go broke, despite having a positive expected return in each period.

If you compound a risky investment strategy over many periods, the best measure of typical results is median (not mean) compound growth.

- The graph of median compound growth against leverage follows an inverted-U pattern.

Adding some leverage initially increases median compound growth, but only up to an optimal level of leverage L*.

- Leverage above (2L* 1) leads to lower growth than no leverage.

- Leverage above 2L* leads to negative growth: the investor eventually goes broke.

A day in the life

Sushil starts work between 7am and 8am, rather than 7am sharp – he is “not a good morning person”.

- Most won’t work out, as Sushil always tries to buy and sell well inside the quoted spread.

- At 8am, he places his orders from the list, perhaps up to a dozen.

- He checks for news alerts on his holdings, and then looks at the prices for his `wish list’.

- Next he works through results statements, news releases or broker notes on his 60 or so holdings.

I try to have buy and sell levels written down for as many companies as possible. It is important to be disciplined.

Sushil then moves on to looking for new ideas. He looks at:

- the largest percentage falls of the day

- new 52-week lows

- screens of stocks with low PE ratios, high dividend yields, high net cash

His monitors show graphs of the stocks from his open orders, and others near his buy and sell price levels, plus the RNS feed and prices and traded volumes for the stocks in his portfolio.

- His watchlist of about 100 more stocks is also on display.

He talks to his broker by phone – a dozen or more (short) calls through the day would not be unusual.

He likes to respond more quickly than an institutional investor can, and is not a fan of discussions with others.

- He thinks company meetings are useful, but too time-intensive.

- It is also a matter of comparative advantage: he’s not great at judging people in person.

He does not post much on bulletin boards, but spends a lot of time reading them (mostly ADVFN).

There is stuff I can’t ignore: comments from industry experts, suppliers, customers, disgruntled employees.

He regards reading as the primary task of an investor.

Warren Buffett says 80%. For me, it’s probably 95%.

He works and lives alone, and often works late into the evening.

To call it work is a travesty - I spend all day every day learning more about the world, doing things I enjoy.

Fraud

Sushil’s biggest mistakes have involved frauds.

- He has occasionally taken an activist role, but is not keen.

The trick is to avoid these situations. There are enough nice people to interact with.

Sushil looks at directors’ records in previous companies, their track record of promises and delivery and adverse comments on bulletin boards.

One aspect of investment which nobody writes about is just figuring out if the management are crooks. I keep a little black book (actually a file on my PC ).

Philanthropy

Sushil is not entirely comfortable with the money to be made from the capital markets:

It has always troubled me that playing a zero-sum game is better paid than brain surgery.

He has established a charitable trust, to which he has donated six-figure sums, which are then allocated to charities.

Investment leaves no trace. Nobody will care in 50 years’ time that I made money.

Quotes

For anyone in the top few percent of the population, IQ points are not the limiting factor in investment. Qualities such as recognising your ignorance matter more.

In investment, doing something easy can gain just as much credit as doing something complicated.

Investment isn’t Olympic diving: there are no marks for degree of difficulty. – Warren Buffett

Most investors favour free markets, but Sushil is not so keen:

Markets are about resource allocation but they sometimes don’t do that very well.

He sees money as freedom:

There are two ways of gaining freedom: increase your assets or reduce your wants. I have always tried to use both.

Conclusions

This is an entertaining chapter, with lots of nice quotes, but it’s not one with many lessons for the typical private investor.

- Few of us have the pleasure – and the responsibility – of investing tens of millions of pounds in the markets.

Sushil uses three systems to trade:

- buying a stream of income cheaply (value)

- buying in anticipation of a change in market perception (beauty contest)

- buying in anticipation of a “knowable change in state”

And for new ideas, he looks at:

- the largest percentage falls of the day

- new 52-week lows

- screens of stocks with low PE ratios, high dividend yields, high net cash

I welcome Sushil’s discomfort with leverage, and it’s always good to be reminded of Kelly betting theory.

I also like his post-tax thinking, but his disdain for diversification is harder to accept.

- Most people won’t enjoy the success that Sushil did with the approach he used in his early years.

He now has 60 stocks, which is a significant improvement, but he remains concentrated in his largest positions.

- And he uses diversification largely for liquidity, since he has become a large fish in a small pond.

To say that I am surprised that he invests an eight figure portfolio entirely in small-cap UK stocks is a massive understatement.

- I would have been scaling that sector back to say 10% as soon as the portfolio size was into the first few millions.

Until next time.