The Most Important Thing 2 – Risk and Cycles

Today’s post is our second visit to The Most Important Thing by Howard Marks.

Contents

Risk and return

Chapters 5 through 7 of Marks’ book are about risk, one of the fundamental variables of investing.

Humans are naturally risk averse – they want to take as little risk as possible to achieve their goals.

- And they remember the pain of losses much more acutely than the pleasure of gains.

So you need to consider two things when looking at an investment:

- Can you tolerate the absolute level of risk involved (answering no to this question is why so many people never get beyond cash savings)

- Are the likely returns sufficient to justify the risks involved – because unfortunately, returns are tied to risk.

This is because:

Investors have to be bribed with higher prospective returns to take incremental risks.

If both a U.S. Treasury note and small company stock appeared likely to return 7 per cent per year, everyone would rush to buy the former (driving up its price and reducing its prospective return) and dump the latter (driving down its price and thus increasing its return).

So all things being equal, returns should be proportional to risk.

- The flip side also applies: in assessing returns, you need to take account of the risks taken to achieve them (including leverage, concentration and illiquidity).

Risk-adjusted return and Sharpe ratios are what count.

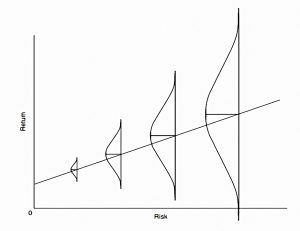

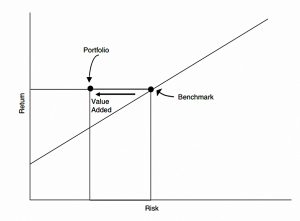

The chart shows two things:

- The straight line is the way most people understand the risk-return relationship.

- The periodic error bars show the true relationship.

As Marks likes to put it:

If riskier investments reliably produced higher returns, they wouldn’t be riskier!

Riskier investments have to offer the prospect of higher returns, but there’s absolutely nothing to say those higher prospective returns have to materialize.

In other words, the higher returns from riskier assets are more uncertain.

What is risk?

Like many people, Marks is uncomfortable with the standard definition of risk as volatility of returns.

- He thinks it doesn’t convey the “necessary sense of peril”.

I have reservations too, but they are mostly around upside volatility, which clearly isn’t a bad thing.

- It also used to grate slightly that the concept was adopted because it makes the maths easier, but in practice, I now find that an advantage.

In the key tasks of portfolio construction and asset allocation, volatility works pretty well.

- We all want to avoid the major drawdowns that stock markets are prone to every decade or two.

Marks doesn’t agree that volatility is the risk most investors care about.

I’ve never heard anyone at Oaktree say, “I won’t buy it, because its price might show big fluctuations”.

It’s true that people think about volatility in terms of loss of capital, but during the downturn, that’s effectively the same thing.

- Investors who can ride out volatility without feeling they have lost something probably won’t worry about it in the first place, but they are in the minority.

You can read more about this in Volatility Is Not Risk.

Underperformance

The only way not to underperform at some point is to go passive.

- Of course, even market cap index funds underperform due to costs.

- And they also underperform relative to better benchmarks (eg. equally weighted indices).

But Marks’ point is that even the best investors will underperform sometimes if they stick to a single approach.

Specifically, in crazy times, disciplined investors willingly accept the risk of not taking enough risk to keep up.

(See Warren Buffett and Julian Robertson in 1999. That year, underperformance was a badge of courage because it denoted a refusal to participate in the tech bubble.)

A specific form of underperformance risk is career risk:

Managers (or “agents”) may not care much about gains, in which they won’t share, but may be deathly afraid of losses that could cost them their jobs.

Which means they won’t take on the right amount of risk – they want an average performance relative to their peers.

Subjectivity

As a hardcore value investor, Marks believes that the assessment of risk is subjective and not “machinable”.

The assessment should be based on:

(a) the stability and dependability of value and (b) the relationship between price and value.

He accepts the Sharpe ratio as the best tool we have:

This calculation seems serviceable for public market securities that trade and price often. For private assets lacking market prices there’s no alternative to subjective risk adjustment.

The normal distribution

Investors are required to make judgments about future events. To do that, we settle on a central value around which we think events are likely to cluster. We [also] need a distribution that describes all of the possibilities.

Most phenomena that cluster around a central value form the familiar bell-shaped curve, with the probability of a given observation peaking at the centre and trailing off toward the extremes, or “tails.”

As we know from the credit crisis of 2008, not all bell-shaped distributions are normal distributions.

- Largely due to emotional and psychological quirks of humans, many financial processes have what are known as “fat tails”.

This means that extreme outcomes (including “black swans”) occur much more frequently than people might expect.

Recognising risk

People vastly overestimate their ability to recognize risk and underestimate what it takes to avoid it; thus, they accept risk unknowingly and in so doing contribute to its creation.

That’s why it’s essential to apply uncommon, second-level thinking to the subject. Risk arises as investor behaviour alters the market.

Investors bid up assets, accelerating into the present appreciation that otherwise would have occurred in the future, and thus lowering prospective returns.

Most investors think quality, as opposed to price, is the determinant of whether something’s risky. But high-quality assets can be risky, and low-quality assets can be safe.

High risk comes primarily with high prices, and too-high prices often come from excessive optimism and inadequate scepticism and risk aversion.

Contributing underlying factors can include low prospective returns on safer investments, recent good performance by risky ones, strong inflows of capital, and easy availability of credit.

The value investor thinks of high risk and low prospective return as nothing but two sides of the same coin, both stemming primarily from high prices.

Risk arises when markets go so high that prices imply losses rather than the potential rewards they should.

In bull markets, people tend to say, “Risk is my friend. The more risk I take, the greater my return will be. I’d like more risk, please.”

Risk cannot be eliminated; it just gets transferred and spread. And developments that make the world look less risky usually are illusory, and thus in presenting a rosy picture, they tend to make the world riskier.

When everyone believes something is risky, their unwillingness to buy usually reduces its price to the point where it’s not risky at all. Broadly negative opinion can make it the least risky thing since all optimism has been driven out of its price.

The investment process

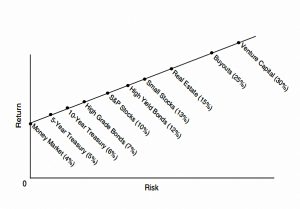

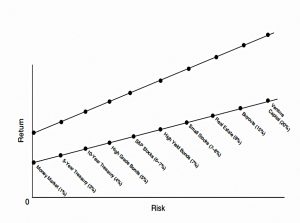

Marks discusses the investment process in terms of a series of comparisons between a risky and a less risky asset, with the risky one needing to provide a higher return if it is to be purchased:

- the 30-day bill vs the 10-year note

- the 10-year Treasury vs a 10-year corporate bond

- a corporate bond vs a junk bond

- bonds vs the S&P 500

- the S&P vs the NASDAQ

This leads to the capital market line.

Marks notes that with the risk-free rate lower today, (( and now even lower than when he wrote the book and the underlying articles )) so are all the other returns.

- The slope of the line is also lower, indicating a lower risk premium.

Investors have fallen over themselves in their effort to get away from low-risk, low-return investments [and] risky investments have been very rewarding for more than twenty years.

Controlling risk

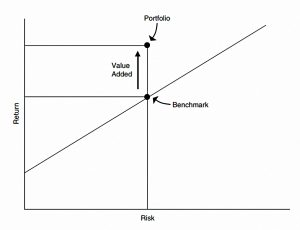

Marks (like me) thinks that great investors are those who take a lower level of risk for the returns they receive.

- But it’s the speculators with the highest absolute returns who will get their names in the papers.

Risk control will never be popular during good times (since it won’t be tested).

- But just because times are good doesn’t mean that risk control isn’t needed.

- Things could be bad – and your risk control might then be tested.

Over a full career, most investors’ results will be determined more by how many losers they have, and how bad they are, than by the greatness of their winners. Skilful risk control is the mark of the superior investor.

Alpha

Marks explains that the kind of alpha most people talk about is higher returns for a market level of risk.

But there’s another kind of alpha – market returns for a lower level risk.

- There’s even a third kind (my favourite) – superior returns for lower risk.

Black swans

You can’t prepare for the worst case. It should suffice to be prepared for once-in-a-generation events.

But a generation isn’t forever, and there will be times when that standard is exceeded. The events of 2007/008 prove there’s no easy answer.

Risk control is the best route to loss avoidance. Risk avoidance, on the other hand, is likely to lead to return avoidance as well.

Will Rogers said, “You’ve got to go out on a limb sometimes because that’s where the fruit is.” None of us is in this business to make 4 per cent.

Cycles

Just about everything is cyclical. Trees don’t grow to the sky. Few things go to zero.

Some of the greatest opportunities for gain and loss come when other people forget this.

The basic reason for the cyclicality in our world is the involvement of humans. People are emotional and inconsistent, not steady and clinical.

Cycles will never stop occurring. If there were such a thing as a completely efficient market, and if people really made decisions in a calculating and unemotional manner, perhaps cycles would be banished. But that’ll never be the case.

Every decade or so, people decide cyclicality is over. They think either the good times will roll on without end or the negative trends can’t be arrested.

They talk about “virtuous cycles” or “vicious cycles”– self-feeding developments that will go on forever in one direction or the other.

You may remember that Gordon Brown once claimed to have ended boom and bust.

- Another way of looking at this is as an example of “this time it’s different”.

The next time you’re approached with a deal predicated on cycles having ceased to occur, remember that invariably that’s a losing bet.

The credit cycle

The credit cycle deserves a very special mention for its inevitability, extreme volatility and ability to create opportunities for investors attuned to it. Of all the cycles, it’s my favourite.

Here’s Marks’ description of the cycle:

- During a period of prosperity, providers of capital thrive and increase their capital base.

- Risk aversion disappears because of a lack of bad news.

- Capital providers compete for market share by lowering their credit standards and returns (demanded interest rates).

- Eventually, they finance borrowers and projects that shouldn’t get money.

- Losses begin, and lenders retract.

- Risk awareness rises and loans become harder to get.

- Companies and borrowers are starved of capital, leading to defaults and bankruptcies.

At some point, lenders are drawn back by the potential high returns (from high interest rates and high creditworthiness).

- Unfortunately, since the 2008 crisis, we seem to be living through the exception to this rule, with rates remaining low.

Conclusions

That’s it for today.

- I’ve enjoyed today’s section of the book a bit more than last time.

Mark remains too much of a value investor for me, and the book’s origins as a series of letters mean that it’s sometimes repetitive.

- But it’s an entertaining read and contains a lot of wisdom.

We’re about forty per cent of the way through now, with three more articles to come (plus a summary).

- Next up are The Pendulum, Negative Influences, Contrarianism and Bargains.

Until next time.