The Most Important Thing 5 – Defence, Pitfalls and Adding Value

Today’s post is our fifth visit to The Most Important Thing by Howard Marks.

Investing Defensively

Chapter 17 is about the choice between making more money and avoiding losses.

Marks begins by looking at Charles Ellis’ article “The Loser’s Game”.

- The analogy here is that while pro tennis involves hitting winners, amateur tennis is all about avoiding hitting losing shots “unforced errors”.

The same thing applies (according to Ellis) to investing.

According to Marks:

The choice between offense and defense investing should be based on how much the investor believes is within his or her control. In my view, investing entails a lot that isn’t.

Investing is full of bad bounces and unanticipated developments, and the dimensions of the court and the height of the net change all the time. The thinking and behavior of the other players constantly alter the environment.

Even if you do everything right, other investors can ignore your favorite stock; management can squander the company’s opportunities; government can change the rules; or nature can serve up a catastrophe.

He concludes that defence (avoiding mistakes) should be an important part of every investor’s game.

Marks things that there are a lot of parallels between investing and sports, particularly football (the non-US kind).

- In football, the payers are largely fixed for the game, and the squad of 14 must deal with both attack and defence.

Few people (if any) have the ability to switch tactics to match market conditions on a timely basis. So investors should commit to an approach – hopefully one that will serve them through a variety of scenarios.

Mark’s approach is to ignore tactical timing and focus on superior security selection in both up and down markets.

- Which is pretty much the opposite of my approach.

Oaktree portfolios are set up to outperform in bad times, and that’s when we think outperformance is essential. Clearly, if we can keep up in good times and outperform in bad times, we’ll have above-average results over full cycles with below-average volatility.

For Marks, there are two parts to defence. The first is avoiding losing stocks:

This is best accomplished by conducting extensive due diligence, applying high standards, demanding a low price and generous margin for error (see and being less willing to bet on continued prosperity, rosy forecasts and developments that may be uncertain.

The second part is keeping out of the market in poor years and especially crashes.

This requires thoughtful portfolio diversification, limits on the overall riskiness borne, and a general tilt toward safety.

So Marks is against portfolio concentration and the use of leverage.

Margin of safety

Marks talks about the margin of safety – also called margin for error – which he attributes to Buffett, but I think comes from Ben Graham (and was made even more famous by Seth Klarman’s book of the same name).

- The margin of safety allows you to come out ahead even when things don’t turn out as well as you hoped.

Low price is the ultimate source of margin for error.

Insisting on a margin of safety will mean turning down opportunities that don’t have one.

- While times are good, this will lead to underperformance.

- When times are bad, this will lead to outperformance.

Defensive investing sounds very erudite, but I can simplify it: Invest scared! Worry about the possibility of loss.

Worry that there’s something you don’t know. Worry that you can make high-quality decisions but still be hit by bad luck or surprise events.

Investing scared will increase the chances that your portfolio is prepared for things going wrong. And if nothing does go wrong, surely the winners will take care of themselves.

Pitfalls

Chapter 18 is more of the same – avoiding mistakes.

You could require your portfolio to do well in a rerun of 2008, but then you’d hold only Treasurys, cash and gold. Is that a viable strategy? Probably not.

So the general rule is that it’s important to avoid pitfalls, but there must be a limit. And the limit is different for each investor.

I think of the sources of error as being primarily analytical/intellectual or psychological/emotional.

Marks says there are too many potential analytical errors to go through them all.

One type of analytical error that I do want to spend some time on, however, is what I call “failure of imagination.”

By that, I mean either being unable to conceive of the full range of possible outcomes or not fully understanding the consequences of the more extreme occurrences.

Relying to excess on the fact that something “should happen” can kill you when it doesn’t. The success of your investment actions shouldn’t be highly dependent on normal outcomes prevailing; instead, you must allow for outliers.

Marks also notes that people are bad at understanding correlations between assets, and also the risk of contagion (as in 2008).

The psychological errors have largely been discussed in previous chapters:

- greed and fear

- willingness to suspend disbelief and skepticism

- ego and envy

- the drive to pursue high returns through risk bearing

- and the tendency to overrate one’s foreknowledge.

Marks singles out the willingness to believe that “it’s different this time”.

- This applies to new tech, the business cycle, creditworthiness rules and valuations norms.

Another important pitfall is the failure to recognize market cycles and manias and move in the opposite direction. Extremes in cycles and trends don’t occur often, but they give rise to the largest errors.

Marks has a few rules about what to look for in a crisis:

- too much capital, badly allocated

- investors accepting low returns (high prices) and low margin for error

- widespread disregard for risk

- inadequate due diligence

- capital is given to innovative but unproven businesses and investments

- psychological and technical factor swamping fundamentals

Adding Value

Chapter 19 brings us right back to the beginning of the book and the ability of second-level thinkers to outperform the market.

This involves explaining the difference between beta (sensitivity to market movements) and alpha (outperformance from skill).

Marks covers some of the tactics available to active investors:

- overweighting high beta stocks

- using leverage

- stock-picking

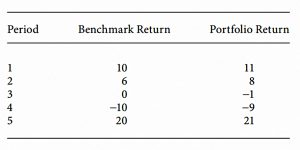

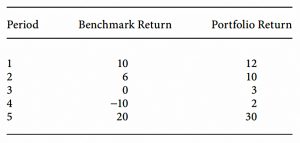

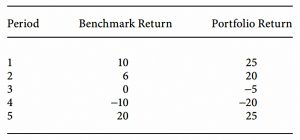

He compares results from a manager with those of a benchmark, in order to determine whether the manager has any skill.

The first manager matches the benchmark in returns in each of the fives years he looks at.

- the second delivers half the market return (up or down)

- the third delivers double the market return (up or down)

None of these three managers has skill.

The fourth has a little.

The fifth has a lot.

The sixth has even more, but with volatility.

- Risk-adjusted returns are ultimately what is important.

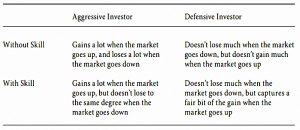

Marks supplies a matrix comparing aggression and skill:

The key to this matrix is the symmetry or asymmetry of the performance. Without skill, aggressive investors move a lot in both directions, and defensive investors move little in either direction.

The performance of investors who add value is asymmetrical. The percentage of the market’s gain they capture is higher than the percentage of loss they suffer.

In good years in the market, it’s good enough to be average. Our clients don’t expect to bear the full brunt of market losses when they occur, and neither do we. Thus, it’s our goal to do as well as the market when it does well and better than the market when it does poorly.

This requires beta on the way up and alpha on the way down.

Putting it all together

The final chapter in the book attempts a summary of what has gone before.

I’ll keep it brief:

- value is the best foundation for success

- you need superior insight than others

- your estimate of intrinsic value needs to be right

- buying below value is the route to success, and to limiting risk

- the relationship between price and value is influenced by psychology and technicals, which can dominate fundamentals in the short run.

- extreme price swings provide opportunities (for both profits and mistakes)

- people think trends will last forever, but everything is a cycle

- contrarianism will help you avoid following the herd and the pendulum (optimism/pessimism, fear/greed, level of risk aversion etc.)

- we never know where we’re going, but we should know where we are (in the cycle)

- things can go against you for a long time – underpriced is not synonymous with going up soon

- being too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong

- the risk that matters most is the risk of permanent loss

- riskier investments have a wider range of possible outcomes and a higher probability of loss

- extra risk must be outweighed by the extra return

- correlation is understood by few but can be used to control portfolio risk

- defensive investing beats aggression in the long run

- if we avoid the losers, the winners will take care of themselves

- avoid doing the wrong thing – risk control is key and margin for error is critical

- the margin for error involves buying low, diversifying and avoiding leverage

- focus on the knowable – industries and companies – rather than the unknowable (the macro future)

- the more micro your focus, the likelier you can learn things that others don’t know

- investors that truly add value perform even when their style doesn’t suit the market (asymmetric returns, more and bigger winners than fewer and smaller losers)

I don’t agree with all of that – particularly the emphasis on value and on bottom-up rather than top-down investing, but it’s not a bad set of rules.

Conclusions

That’s it – we’ve made it through the book.

It’s an entertaining read, and I would recommend it to any serious investor.

- But the focus on bottom-up value means that it won’t have much impact on my day-to-day investing behaviour.

I’ll be back in a few weeks with a summary of the whole book.

- Until next time.