The Upside of Irrationality 3 – Adaptation

Today’s post is our third visit to Dan Ariely’s second book – The Upside of Irrationality.

Contents

Adaptation

Chapter 6 is about when and why we get used to things.

I mentioned earlier that humans are attachment machines – we can grow sentimental about anything.

- The other thing that defines us (apart from language, cooperation, opposable-thumb-supported tool-making and the sweat-advantaged ability to outrun any other animal on the planet) is adaptation.

Perhaps the best example is hedonic adaptation.

- Six months after the event, lottery winners and people rendered paraplegic in accidents (usually on motorcycles) have each returned to the level of happiness they had before the event.

Put simply (and I write this under coronavirus lockdown), we can get used to anything.

Dan starts the chapter with the story of the boiling frog, who sits in a pan of gradually warning water until he dies.

- This is a (possibly apocryphal) tale of too much adaptation.

Once upon a time, Al Gore used the frog story to explain our supposed ignorance about global warming.

- Those days are long gone, and the debate now is how much of civilised life we (and in particular, major carbon emitters in the emerging economies) are prepared to sacrifice.

My instincts tell me not enough.

Dan mentions human physical adaptation, such as to the low light of a movie theatre.

The same process takes place when we first encounter a new smell, texture, temperature, or background noise. Initially, we are very aware of these sensations. But as time passes, we pay less and less attention to them until, at some point, we adapt and they become almost unnoticeable.

Dan characterises adaptation as a novelty filter.

- We need to efficiently learn about the world, and so we focus on the things that are new and/or changing.

If the air smells the same as it has for the past five hours, you don’t notice it. But if you start smelling gas as you read on the couch, you quickly notice it, get out of the house, and call the gas company.

Pain

As you will recall, Dan was badly burned as a teenager and developed a high tolerance for pain (eg. no anaesthetic at the dentist) (( Note: this approach was also forced upon me as a teenager and mentally scarred me so badly that I have never returned to this day ))

- Dan mentions that his physiology professor had lost his legs on Israeli national service, and had also developed a high pain threshold.

We began to wonder whether we were just two strangely masochistic individuals or whether there was something about our long exposure to pain that made the relatively minor experience of tooth drilling seem less daunting.

During World War 2, Henry Beecher found that soldiers requested less medication than did civilians.

The amount of pain we end up experiencing is not only a function of the intensity of the wound, he concluded, but it also depends on the context in which we experience the pain and the interpretation and meaning we ascribe to it.

Dan and his professor, of course, decided to test their hypothesis.

- They used subjects from a country club for injured army veterans.

The task was to keep your hand in a tub of water at 48 degrees C (118F).

- They also had to indicate at which point keeping their hand in there became painful.

The forty subjects (injured on average 15 years earlier) were divided by doctors into badly injured and mildly injured groups.

The participants who had been mildly injured reported that the hot water became painful (pain threshold) after about 4.5 seconds, while those who had been severely injured started feeling pain after 10 seconds.

More interestingly, those in the mildly injured group removed their hands from the hot water (pain tolerance) after about 27 seconds, while the severely injured individuals kept their hands in the hot water for about 58 seconds.

Dan had a cut-off of 60 seconds in the hot water to make sure no one was permanently injured (but the subject didn’t know this unless they lasted for 60 seconds).

- All but one of the badly injured group hit this stop.

Afterwards, Dan noticed that two terminal patients with a disease rather than trauma had much lower pain thresholds even than the mildly injured group.

I wondered if the contrast between their types of ailments and the types of injuries that the other participants (and I) had suffered could offer a clue as to why severe injuries would lead people to care less about pain.

Dan’s theory is that pain directed towards recovery becomes more bearable.

People with injuries like mine learn to associate pain with hope for a good outcome. On the other hand, the two chronically ill individuals could not make any connection between their pain and a hope for improvement.

They most likely associated pain with getting worse and the proximity of death. Pain must have felt more frightening and more intense for them.

Dan pours cold water on the idea that the experience of childbirth means that women have a greater pain tolerance than men.

- His experiments with hot water showed the opposite.

Hedonic adaptation

Dan moves on to hedonic adaptation.

- His examples are how we adjust (in both directions) to the things we loved and hated about a new house.

And how job satisfaction is linked to changes in pay, rather than the absolute amount of pay.

- He also mentions the paraplegics and lottery winners experiment.

Although internal happiness can deviate from its “resting state” in reaction to life events, it usually returns toward its baseline over time.

The problem is that if we fail to predict this adaptation in the future, our decision-making in the present will be sub-optimal.

We don’t end up being as happy as we thought we’d be when good things happen to us, and we are not as sad as we expect when bad things occur.

Dan quotes a long-term (38 weeks) study on romantic breakups amongst students:

The breakups were not as earth-shattering as the students had expected and the emotional grieving was much shorter-lived than they had originally assumed.

I’m not convinced this finding can be generalised to adults, and to longer-term relationships.

Hedonic Treadmill

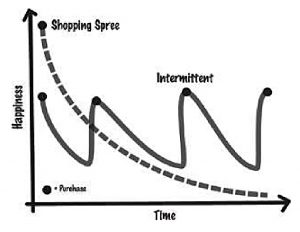

The downside of hedonic adaptation for investors is that because we get used to things, including stuff, we want more of it – bigger and better (and more expensive).

- As our income rises, so does our spending.

And instead of remaining true to our internal scorecard, we try to Keep Up With The Joneses.

- You can’t buy your way to happiness, but it takes some people a long time to learn this.

You can, however, buy your way to an inadequate savings rate.

David Schkade and Danny Kahneman looked at this by comparing Calinfornians with mid-westerners.

Midwesterners think that fair-weather Californians are, overall, considerably more satisfied with their lives, while Californians think that midwesterners are considerably less satisfied overall.

This is a largely weather-based comparison.

New transplants do indeed experience the expected boost or reduction in quality of life due to the weather. But, much like everything else, once adaptation hits and they get used to the new city, their quality of life drifts back toward its premoving level.

Interrupting adaptation

Leif Nelson and Tom Meyvis tested how interruptions (“hedonic disruption”) would affect adaptation.

Dan asks us to imagine splitting enjoyable tasks and chores into blocks.

- Would this help or make things worse?

Before looking at the results, I think there are two effects here – a daily one and a long-term one.

- Each day, I know that I have to get the hardest thing on my list done first (I’m not great when I wake up, so “first” usually means starting after an hour or so).

This is a willpower thing, known as “eat the frog (first)”.

- But on a longer-term basis, breaking large and off-putting tasks into small blocks and getting one block done each day really helps.

On the other hand, I would happily break pleasurable things into sections, in order to savour them more.

- After a certain amount of time, even sipping champagne on a Meditteranean beach has diminishing returns.

Leif and Tom found that people want to disrupt annoying experiences but prefer to enjoy pleasurable experiences without any breaks.

Which sounds completely wrong to me. Leif and Tom agree:

People will suffer less when they do not disrupt annoying experiences, and enjoy pleasurable experiences more when they break them up.

Any interruption, they guessed, would keep people from adapting to the experience, which means that it would be bad to break up annoying experiences but useful to interrupt pleasurable ones.

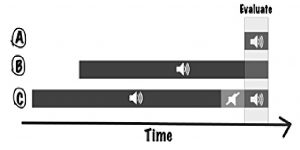

In the experiment, “pain” meant listening to an industrial vacuum cleaner for five or 40 seconds, or 40 then 5 seconds (after a break).

- Subjects then rated their irritation.

The most pampered participants were far more irritated than those who listened to the annoying sound for much longer. The interruption made things worse. The adaptation went away, and the annoyance returned.

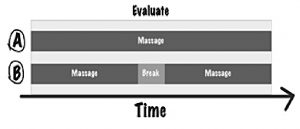

“Pleasure” was time spent in a massage chair – 180 seconds, or 80 then a 20-second break, then another 80 seconds of massage.

Those who underwent the shorter massages with the break not only enjoyed their experiences more but they also said they would pay twice as much for the same interrupted massage in the future.

Mastering adaptation

Dan’s first tip is to spread out “treat” spending so that we get more out of it.

- Since the flesh is weak, the best way to do this is to have a budget.

Allocate a (small) amount of money each month to “stupid spending”, and don’t worry about whether you waste it.

Slow down pleasure. A new couch may please you for a couple of months, but don’t buy your new television until after the thrill of the couch has worn off.

If you have to cut back, on the other hand, do it all at once.

- Avoid the “death of a thousand cuts”.

Dan also uses adaptation to explain why splurging on experiences rather than “stuff” can make more sense.

- You have less time to adapt to the experiences.

I think this is largely true, but at the same time, skimping on something that you use for several hours every day (phone, PC, TV, office chair, sofa, mattress) is a false economy.

- I also have one really good kitchen knife and a few decent pans.

Wine

Dan quotes a friend of his on wine:

He wanted to become an expert on wines that cost $15 or less. Tom’s idea was that if he started buying fancy $50-a-bottle wines, he would would no longer be able to derive any pleasure from cheaper wines.

This is the approach I have followed my whole life.

- My favourite wines are in the £40 to £100 a bottle bracket, but I can’t afford to drink those regularly.

Not only that, the people I drink wine with actively dislike those kinds of wines.

- So mostly I drink £10 wine, and just occasionally treat myself to a nice bottle (my birthday and Xmas, usually).

Apparently, Dan’s friend managed to stick entirely to $15 wine, so he must be tougher than me.

- I have to say, though, that I have never adapted to the cheap wine, and I still massively prefer more expensive bottles (at least £25 to £30).

Comparisons

Along with interruptions, comparisons will slow down the process of adaptation.

- Dan imagines settling for a cheaper laptop than our ideal:

You’ll most likely get used to it over time. That is, unless the person in the cubicle next to you has the laptop that you originally wanted. In the latter case, the daily comparison will make you less happy.

Another reason to not Keep Up With The Joneses – comparison is the thief of joy.

- Ideally, try not to think about the Joneses at all – use an internal rather than an external scorecard.

Conclusions

That’s it for today.

- It’s been slow (but enjoyable) going today, so we’re only around 60% of the way through the book.

So there will still be two more articles in this series (along with a summary).

- Today was more fun, but I’m still looking for the upside.

Until next time.