The Upside of Irrationality 1 – Motivation and Meaning

Today’s post is our first visit to Dan Ariely’s second book – The Upside of Irrationality.

Contents

Procrastination and Side Effects

Dan starts the book with a story about the time he got hepatitis from a blood transfusion whilst in hospital for his burns.

At the time the doctors didn’t know which type of hepatitis Dan had, only that it wasn’t A or B.

- Eight years later he had a flare-up and found out he had type C, which had recently been discovered.

There was also a new drug (interferon) and Dan became part of an experimental study.

- The drug made him sick for some hours after each injection, which led to procrastination over injecting himself.

At the end of the eighteen-month trial, the doctors told me that the treatment was successful and that I was the only patient in the protocol who had always taken the interferon as prescribed. Everyone else in the study had skipped the medication numerous times.

Dan used movies to motivate himself – he would watch one after each injection (since watching a screen was about all he could do while nauseous.

All of us have important tasks that we would rather avoid. Sadly, most of us often prefer immediately gratifying short-term experiences over our long-term objectives.

We’re back to Dan’s central theme that humans aren’t rational and don’t always do what is best for them.

- He bemoans the lack of safety measures in the financial markets in comparison with those in the driving ecosystem (he is writing soon after the 2008 crash).

- He notes the downsides of potentially useful technologies like smartphones and food productivity (distraction and obesity, respectively).

He sets out the goal of behavioural economics as:

To understand human frailty and to find more compassionate, realistic, and effective ways for people to avoid temptation, exert more self-control, and ultimately reach their long-term goals.

Bonuses

In Chapter 1, Dan looks at motivation, starting with lab rats who have to learn which parts of a new daily maze are wired for electric shocks.

- The original experiment sought to establish a link between the intensity of the shocks and the speed of learning.

Similar logic is used to justify large bonuses for CEOs.

What happened with the rats was that up to a point, bigger shocks meant faster learning.

- But very large shocks led to a reduction in performance – the rats became paralysed by fear.

Incentives can be a double-edged sword. Up to a certain point, they motivate us to learn and perform well. But beyond that point, motivational pressure can be so high that it actually distracts an individual from concentrating on and carrying out a task.

So Dan designed an experiment to test the impact of bonuses.

- To keep the budget down, he ran the experiment in villages in India, where monthly spending averaged $11.

Some subjects could earn a day’s pay as a bonus, some two weeks’ pay and some five months’ pay.

- Subjects were allocated randomly to one of the groups (by rolling a die).

The tasks used involved creativity and problem-solving, rather than pure effort.

- Dan anticipated that large bonuses would work well for simple, mechanical tasks, and would not backfire.

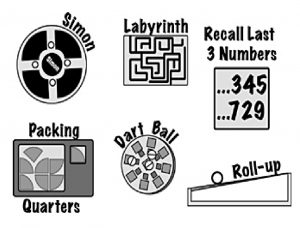

Here are the six tasks they used:

The base pay was received for achieving a medium performance in the task, with the bonus reserved for good performance.

- Poor performance meant no pay at all.

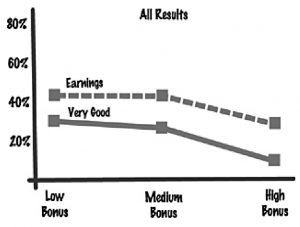

We found that those who could earn a small bonus [or] the medium-level bonus did not differ much from each other. We concluded that since even our small payment was worth a substantial amount to our participants, it probably already maximized their motivation. Those who stood to earn the most demonstrated the lowest level of performance.

The impaired performance was present across all tasks, including the simpler ones (Dart Ball and Roll-Up).

Dan had hoped to increase incentives by adding loss aversion to the experiment.

- Subjects would be given all the money upfront, and would progressively lose it as they failed to reach the good level of performance on tasks.

This would mimic the way that executives imagine their bonus throughout the year, in advance of receiving it.

But the pile of money made the first subject too nervous to perform any task well, and the second gut just ran off with the money.

- So that plan was abandoned.

A follow-up experiment with MIT students involved both a cognitive task (math problems) and a mechanical one (key presses).

- Here the high bonus was $600.

Each subject performed each task twice – once for a low bonus and once for a high bonus.

When the job at hand involved only clicking two keys on a keyboard, higher bonuses led to higher performance. However, once the task required even some rudimentary cognitive skills, the higher incentives led to a negative effect on performance.

So bonuses for executives (as opposed to bricklayers) probably don’t work.

Bonuses for traders probably do work, but there remains the issue of asymmetry.

- Since big wins lead to big bonuses, and big losses don’t lead to big fines, bonuses encourage risk-taking.

Rational employers would not offer bonuses for cognitive tasks.

- Unfortunately, people are not rational in this situation, since most people predict that large bonuses would lead to outperformance on cognitive tasks.

This is particularly true of people in the firms which award large bonuses.

Dan quotes Upton Sinclair:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

Bankers think that they are special people, who work better under stress.

Dan could afford to test bankers, so instead, he looked at basketball players.

Clutch players – the basketball heroes who sink a basket just as the buzzer sounds – are paid much more than other players, and are presumed to perform especially brilliantly during the last few minutes or seconds of a game, when stress and pressure are highest.

Dan and a colleague asked professional coaches to identify the best clutch players in the NBA, and then studied footage of their games.

- He compared performance in the last five minutes of the first half with that during the last five minutes of the second half.

He also compared their performance with non-clutch players in the same games.

Nonclutch players scored more or less the same in the low-stress and high-stress moments, whereas there was actually a substantial improvement for clutch players during the last five minutes of the games.

Maybe the bankers were right.

But – clutch players did not improve their skill; they just tried many more times. Their shots were no more accurate.

So the bankers – performing a more cognitive task – should struggle to improve their performance under pressure.

- I see the extra shots taken by the clutch players as analogous to the extra risk-taking motivated by large bonuses.

Public speaking

Dan knows from personal experience that public speaking is stressful.

- His next experiment looked at social pressure using anagrams.

Sometimes the subjects worked along in private cubicles.

- At other times they used a large blackboard in front of the other participants.

The participants solved about twice as many anagrams in private as in public.

Social pressure has also been demonstrated in animals (rats as we saw earlier, and even in cockroaches, using simple and complex maze tasks).

So what can we conclude:

It’s difficult to create the optimal incentive structure for people, and higher incentives don’t always lead to the highest performance.

Financial incentives don’t operate in a simple way on the quality of output from our brains. Nor is it at all clear how much of our mental activity is really under our direct control, especially when we are under the gun and really want to do our best.

Our tendency to behave irrationally and in ways that are undesirable might increase when the decisions are more important.

Dan suggests keeping bonuses small or using a five-year moving average as a smoothing (and de-stressing) device.

Lego and Labour

Most of us understand the deep interconnection between identity and labor. Children think of their potential future occupations in terms of what they will be, not about the amount of money they will earn.

I’ve certainly noticed this since I retired.

- People have no answer when you say that you do “nothing”.

Our jobs are an integral part of our identity, not merely a way to make money in order to keep a roof over our heads and food in our mouths. Many people find pride and meaning in their jobs.

Yet economics treats workers as lab rats and production units.

Contrafreeloading

Many animals prefer to earn food rather than simply eating identical but freely accessible food.

- Dan found this out for himself when he owned a parrot.

The phenomenon was first discovered in rats by Glen Jensen, in the 1960s.

- He used Skinner boxes – cages with a lever that dispenses a food pellet (only when a light is on).

When a cup of free pellets is added to the cage, rats continue to press the bar for more food.

- 44% of Jensen’s rats used the bar for more than half of their pellets.

Jensen discovered that many animals – including fish, birds, gerbils, rats, mice, monkeys, and chimpanzees – tend to prefer a longer, more indirect route to food than a shorter, more direct one. The only species that prefers the lazy route is the commendably rational cat.

Contrafreeloading contradicts the simple economic view that organisms will always choose to maximize their reward while minimizing their effort.

Dan wanted to find out if humans exhibit contra-freeloading.

Meaning

What is it aside from a paycheck, I wondered, that confers meaning on work? Is it that we enjoy feeling challenged and completing a task? Perhaps we hope that someone else will ascribe value to what we’ve produced?

Dan talks a little about blogging.

Blogs have two features that distinguish them from other forms of writing. First, they provide the hope or the illusion that someone else will read one’s writing [Since they are public – and second] blogs also provide readers with the ability to leave their reactions and comments.

But as Dan points out:

Most blogs have very low readership.

I struggle with this a little myself.

- I would rather have ten times the audience that I have currently – but even a few engaged people is somewhat motivating.

I also have the advantage that I would be doing most of the work (admittedly, to a less polished standard) on my own behalf in any case.

Dan’s experiment paid people to build Legos (to be specific – Bionicles, small fighting robots).

- The pay was on a diminishing scale – $2 for the first, $1.89 for the second, then $1.78 and so on until subjects wanted to stop.

For half of the subjects, the experimenter dis-assembled robot one whilst the subject assembled robot two (and so on).

- The control group were merely informed that the robots would be disassembled after they had left so that the next subject could use the components.

The participants in the meaningful condition built an average of 10.6 Bionicles and received an average of $14.40. Even after their earnings for each Bionicle were less than a dollar 65 percent kept on working.

Those in the Sisyphean condition built 7.2 Bionicles (68 percent) and earned an average of $11.52. Only 20 percent constructed Bionicles when the payment was less than a dollar per robot.

Subjects were able to correctly predict that meaning would increase productivity, but they underestimated the size of the effect.

Dan also investigated how subjects felt about Legos in general and about the experiment in particular.

The more a participant loved playing with Legos, the more Bionicles he or she would complete. In the meaningful condition the correlation was high, but it was practically zero in the Sisyphean condition.

If you take people who love something and you place them in meaningful working conditions, the joy they derive from the activity is going to be a major driver in dictating their level of effort. However, if you place them in meaningless working conditions, you can very easily kill any internal joy they might derive from the activity.

All the participants most likely understood that the whole exercise was silly. But watching their creations being deconstructed in front of their eyes was hugely demotivating.

A second experiment paid subjects to find double letter Ss on a sheet of paper.

- They had to find 10 per sheet and were paid on a declining scale once again ($0.55, $0.50 etc – so for 11 sheets maximum).

In the “acknowledged” condition, subjects wrote their name on their answer sheet and got a positive nod from the experimenter when they handed it in.

- In the “ignored” condition, neither of these things happened.

- In the “shredded” condition, their answer sheets were shredded in front of them.

49 percent of those in the acknowledged condition went on to complete ten sheets or more, whereas only 17 percent in the shredded condition completed ten sheets or more.

Participants in the acknowledged condition completed on average 9.03 sheets of letters; those in the shredded condition completed 6.34 sheets; and those in the ignored condition completed 6.77 sheets (and only 18 percent of them completed ten sheets or more).

So the ignored condition was much closer to the shredded condition.

Sucking the meaning out of work is surprisingly easy.

All you have to do is ignore somebody (and their work).

Human motivation is complex. It can’t be reduced to a simple “work for money” trade-off. The effect of meaning on labor, as well as the effect of eliminating meaning from labor, are more powerful than we usually expect.

Dan points out that the efficient division of labour (as derived from Adam Smith’s analysis of a pin factory and developed by Henry Ford and Winslow Taylor) sucks much of the meaning out of work.

One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on, is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; and the important business of making a pin is divided into about eighteen distinct operations.

Dan notes also Marx’s idea of the alienation of labour.

Conclusions

That’s it for today.

- We’re a quarter of the way through the book, so there will be three more articles in this series, plus a summary.

Dan promised us in the introduction that this would be a more optimistic book than his first, but I haven’t seen much sign of that yet.

- Until next time.