Weekly Roundup, 9th January 2018

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with their investing round-table for 2018.

Contents

Investing round tables

After a week off for New Year, we have a lot to get through.

The FT held a round table at the end of the year to look forward to 2018. There were six members of the debating team:

- Merryn Somerset Webb

- Jonathan Eley

- Anne Richards

- Richard Buxton

- Miles Johnson and

- Robert Armstrong.

Of these, three are FT staffers and Merryn also has a regular column.

- Anne runs M&G while Richard is in charge of Old Mutual.

The paper summed up the thoughts of the panel as “more of the same” (MOTS).

RB said that 2018 is a liquidity story:

There are two scenarios: either central bankers hold their nerve, or they blink.

If they withdraw liquidity (in Japan, the US and Europe) then markets could suffer.

- Note that EB is a self-confessed perma-bear who has predicted “ten of the last one crashes”.

MSW thinks that real interest rates will still be negative in 2018, so maybe 2019 will be the year that sees movement as the 30-year interest rate cycle turns.

AR thinks that sentiment rather than liquidity will be the catalyst.

- And with inflation increasing and the jobs markets improving, investors are unlikely to feel negative this year.

MJ thought that the best plan was to buy things you felt were well-priced, and hold them for a long time.

- His tip was US retail (Target for example), as he thinks the idea that Amazon will kill traditional retailers is overdone.

The panel felt that tech firms would be more heavily regulated, more like financial firms are now.

- But this could act like a moat. (( In the same way that Financial Fair Play in football has cemented the positions of the dozen clubs who were the richest at the time that it was introduced ))

RA doesn’t own a house and is “screaming for a housing crisis”.

- Remember that when you next read an FT leader article (he writes them).

He felt that this could be the sentiment change that AR is looking for:

There are two things most people consider when they think about whether they’re rich or poor: do I have a job, and how much is my house worth?

RB thinks that people could be getting the length of the cycle wrong:

After a financial crisis, you should double the economic cycle and add a bit. The usual seven years could become 15 to 18 years.

The panel agreed that stock-picking continues to be hard (witness the struggles of Neil Woodford) and this might not change if we have more of the same.

MSW suggested that the US mid-term elections in the US might provide a catalyst.

What if you get a Jeremy Corbyn-style swing to the left there, with the young pushing back against Trump?

The same tension has hugely affected UK equity markets this year. A socialist government is a lot more frightening than Brexit.

RB:

Capitalism is not working for the under-40s, so they’re voting for socialism. They’ve never experienced socialism, they don’t know what the 1970s were like, and they don’t know what Thatcher had to rescue us from.

They moved on to the housing crisis.

RB:

To solve the UK housing crisis, you’ve got to cross the Rubicon which they will not cross: build on greenbelt. Unless you do that, we’re going to have Jeremy Corbyn as prime minister.

JE, on the other hand, thought that we had probably already seen “peak Corbyn”.

There is no shortage of housing in the UK. There is a problem of distribution of housing, [they] are in the wrong places or they’re owned by the wrong people. … Houses are expensive .. because land is expensive. Building 300K houses a year on expensive land would just result in 300K hastily built houses that no one can afford.

MoneyWeek also held a roundtable with six panellists.

Steve Russell, from Ruffer, felt that the negative would prevail in the end, but it could take some time.

- Rising rates could be the trigger, or earnings growth disappointments.

- But markets would keep going up until then, so it was difficult not to be in the market.

The obvious strategy would be for central banks to raise rates only after growth arrives, but most of the panel felt that wage inflation was imminent, and would force their hand.

- The “precariat” (workers in precarious jobs) want a bigger slice of the pie.

Globalisation (migrating workers, foreign factories) have limited the impact of demographic forces in recent years, but perhaps that era is ending.

The panel also felt that tech firms were in for more regulation (as per financial firms now).

- Jim Mellon couldn’t see any upside in the tech firms.

The panel also debated whether bricks-and-mortar retail was over.

- Walmart and Foot Locker have been fighting back against Amazon recently.

They then started to talk about what they would buy at the moment.

Lucy Macdonald of Brunner liked the look of financials:

Regulation and litigation risk are probably now past the worst. Rising interest rates are good for banks. Everyone is living longer, so we need to save and invest more, which means higher fees for asset managers.

Technology presents interesting opportunities – some of the biggest developers of blockchain right now are financial institutions. I don’t think that’s really priced in yet.

Jim Leaviss of M&G liked Europe and Japan for growth, and EM bonds from Mexico, Brazil and Colombia.

Tim Price liked Japan, too, and also Vietnam.

JM also liked Japan, but saw electric cars and energy storage as the most significant change:

Lithium is going to go through the roof. There’s a huge shortage of it. There’s still no alternative to lithium batteries.

JM also thinks that life expectancy will rise to 110 / 120 within 30 years:

That will change everything. It will transform financial services – for instance, the pension-fund model is finished. Consumption patterns will change too.

JM sees leisure, travel and the longevity industry itself as the beneficiaries.

- He also saw a universal basic income – or a much higher minimum wage – as a response to robots taking more jobs.

SR thought that basic income threatened hyperinflation since the majority of people would receive it, and in a democracy they could vote for its level to be increased.

- JM saw holding gold as the answer to that threat, once the diversion of crypto was over.

SR tipped Teco, M&S and Countryside.

The panel moved on to the passive vs active debate.

Charlie Morris thought that the rise of inflation would replace the momentum trade with the value trade, and the preference for indexing would recede at the same time.

- SR pointed out that in a bubble, indexing maximises your weighting to the bubble assets.

In total, the panel backed eleven investments, but only four were UK-listed:

- Vietnam Opportunities IT (VOF)

- Tesco (TSCO)

- Marks & Spencer (MKS)

- Countryside (CSP)

FOMO

Sticking with prognostication, Ken Fisher had another of his regular bullish columns on market prospects.

- This time he focused on “fear of missing out” (FOMO) as a driver.

He sees the global bull entering its final third, though returns to UK investors could be dampened by continued sterling strength and Brexit pessimism.

- And he reminds us that usually more than a third of bull market returns come in the final third.

Ken thinks we’ve reached optimism, but not euphoria (crypto excepted).

- And it’s this optimism that drives FOMO.

He too expects more of the same (MOTS):

- European stocks should lead US ones higher.

Huge high-quality growth stocks are the ones to look for.

- Ken recommends 25% in tech, 20% in healthcare and 20% in financials (particularly in Europe).

Watch for danger

Following on from his look at investing with hindsight during 2017, John Authers had two columns over the festive break.

- The first was his predictions for 2018.

He starts by pointing out that timing is everything, and that it’s easier to make long-term predictions than short-term ones.

- In the long-term, the economic growth rate dominates.

- And valuation at the point of purchase is always the best predictor of future returns over 10 years or more.

But in the short-term, markets try to anticipate the economy.

- And the momentum effect is stronger than the value effect.

This year, US stocks look expensive, and bonds look even more expensive.

- But momentum remains positive, and investor confidence is high.

The market will turn at some point, but usually volatility increases some time before the peak, which suggests that the turn is not yet imminent.

- Neither does a recession seem around the corner, so perhaps 2018 is not the year.

Of course, central banks may withdraw liquidity, which could have an effect.

But a rise in 10-year Treasury yields is the thing to look for.

- A strong economy could lead to rate rises, inflation rises, yield rises – and stock and bond price falls.

Like me, John recommends mostly stocks, but underweight bonds and overweight cash.

- A bond sell-off is the greatest risk, and extra cash mean you can pick up the pieces if stocks, bonds or both crash.

A week later, John recognises the healthy state of the world economy, but fears that Trump euphoria has arrived.

- Company earnings forecasts are up.

- And so are the markets.

John registers his annoyance that the media keep reporting progress in the obsolete Dow index, rather than the professionally used S&P-500.

- He also debunks the idea that markets are doing better under Trump than they did under Obama (though they are of course now at all-time highs).

But the outsize reaction to the current improvements indicates euphoria.

- Investor sentiment surveys back this up.

- There are more bulls than ever, apart from a week in 2011 and the week in 2009 when the present rally began.

John thinks it could last for more than a year.

- But we need to plan now for its end.

Training wheels

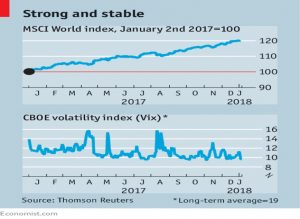

In The Economist, Buttonwood also looked at the prospects for 2018.

- He compared the withdrawal of central bank support to a parent removing the training wheels from a child’s bike.

Investors seem to expect more of the same (MOTS) but Buttonwood fears they may be disappointed.

- He quotes the high level of the CAPE, but this measure has poor short-term predictive power.

A net 45% of fund managers think stocks are overpriced.

- But 48% of them are still overweight stocks.

- Since a net 83% of them think bonds are overvalued.

- And an 59% are underweight bonds.

2017 was not just better than most people expected, it was also much less volatile.

- Investors are betting on MOTS, but there is plenty (withdrawal of liquidity, China slowdown, trade war, real war) that can derail this.

Extrapolation from the recent past is a well-known psychological bias.

- But will it be costly this time?

Hedging against Corbyn

Back in the FT, a slew of their reporters looked at how to hedge against a Corbyn government.

- Unfortunately, the article was better at identifying potential problems than it was at finding solutions.

First up is higher income tax, potentially on those earning more than £70K pa.

- The only way to avoid this would be to emigrate or work less hard.

You might also use tax shelters like pensions, VCTs and EIS, assuming these survive.

- You could also bring forward dividends if you are self-employed or run a company.

CGT is likely to go up too, so selling assets could be profitable.

- And entrepreneurs’ relief could be removed, so some company owners might want to sell up before that happens – potentially to a trust they control.

Of course, family trusts will also be a target for a Labour government.

Wealth taxes were also mentioned in the last labour manifesto, so passing on money early to children might be a good idea.

- A property tax is possible, which could only be avoided by selling your property.

- If enough people did this, it could precipitate a market crash, with dire consequences for the UK economy.

Corporation tax will rise, so firms will try to make lower profits in the UK.

- And there will be measures to plug the gap between income tax and corporate tax rates.

Stamp duty (on shares) is likely to be broadened into a general transaction tax (a Tobin tax).

- Though surely not at the current horrific rate of 0.5%

This will cost jobs, as funds (and investors) move offshore.

A Labour government will also hit UK markets and the price of sterling, so a move into international investment looks prudent.

- You might also want to keep some cash on hand to pick up the pieces in the UK after the initial shock.

Domestic-facing sectors (like housebuilders) would be expected to do worst.

- Those with largely overseas earnings would do better in a sterling crash.

- To find out which is which, just check what happened to a stock after the Brexit vote.

And of course, railways, royal mail, and water and energy companies stand to be nationalised.

- And of course, these form the core of many dividend portfolios.

Labour also plans to nationalise PFI contracts, which will hurt infrastructure ITs.

- And their spending plans involve issuing a lot more debt, which could hurt gilts.

This in turn would put up the annual debt interest bill significantly.

On a related note, Merryn wrote about the need to reboot shareholder capitalism.

- She began with the “insane” remuneration packages enjoyed by company executives.

The reason they exist has to do with share ownership:

- Back in the 1960s, more than 50% of shares were owned by individuals, who could vote down excessive pay.

- By 1990 this was down to 20% and now it’s closer to 10%.

Most people today hold shares via funds and pensions, and even those of us who have individual shares normally use (non-voting) nominee accounts.

- Fund manager might not care about executive pay, but hard-up pensioners probably do.

If we want to get rid of short-termism in corporate decision-making, we need to make it easier for individuals to vote.

- And that means pensioners deciding how their pension fund votes, too.

Good news and bad news

Gemma Tetlow had good news and bad news for millennials this week:

- The good news is that the Resolution Foundation has calculated that they are in line to inherit double the amount that their parents did.

The bad news is that due to increasing life expectancy and the increased age at which people start a family, on average they won’t get the money until they are 61 years old.

Twitter pics

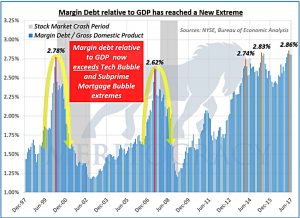

I only have two this week.

The first one is worrying:

- Margin debt has reached record levels as a proportion of GDP.

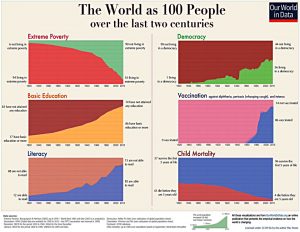

The second is more reassuring:

- It’s one I’ve used before but it’s a favourite and I came across it again over Xmas.

It shows the progress we’ve made over the last two centuries by imagining the world contains only 100 people.

Until next time.