Weekly Roundup, 5th April 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with a review of the first year of the pension freedoms.

Pension freedoms

Josephine Cumbo looked at whether the fears of mass Lamborghini purchases had come to pass.

This time last year, the over-55s were given the option not to buy a poor value annuity in return for all their savings ((In practice the obligation had already been removed for the under-75s, but word hadn’t gotten around to many ))

The big change is the rise in popularity of income drawdown.

- This time last year, only 10% of retirees opted for drawdown, but £6 bn has been withdrawn in the first year.

- People used to leave their pension pots alone until 65 (when the State Pension kicked in) but now a lot more people are starting to draw cash five or ten years earlier.

- This is good news for the Treasury, as pensions are taxable and it brings forward tax receipts.

The consequence of the switch to drawdown and the unaffordability of financial advice for many ((Those with small pots, which form more than half of the market )) following the RDR restrictions ((Which forced IFAs to charge fees rather than live off commissions )) is that there are now a lot more DIY private investors.

- Only 58% of those moving into drawdown took advice.

- And The new DIY investors are making a poor job of shopping around – 58% of new drawdown clients and 64% of those buying an annuity stick with their original provider.

Annuities are a fairly simple product, but I know from my own initial research that drawdown involves lots of complex charges, making products difficult to compare unless you have a firm grip on your investment strategy and withdrawal plans.

- The government attempted to plug the advice gap with the free Pension Wise service, but of the 1M people who have since qualified for their pension, only 50,000 made an appointment (though there were also 2M website visits).

The second big trend is the number of attempted pension scams, with an estimated 11M people being cold-called in the past year.

- I was being called every day for a few months though it seems to have gone quiet recently (or perhaps I’ve just stopped picking up).

- Worryingly, research also suggested that 90% of people can’t spot the warning signs (such as returns that are too good to be true).

Josephine’s third point was that the concern over rash sports car purchases has now been replaced by a fear that people are being too conservative with their money.

- Lots of new retirees are taking money out of their pension and sticking it in a taxable ((Until the new savings allowance goes live this week )) low-interest cash accounts.

Drawdown

Don Ezra looked at the strategies available to those moving into drawdown.

- He characterised the choice between annuities and drawdown as whether you’d like to sleep well (with the safety of annuities) or eat well (from the asset growth within drawdown).

- Most people want to sleep well and worry about outliving their pension pot, but Don thought that it might be possible to do both.

The traditional approach is to come up with an annual sustainable withdrawal rate (SWR), commonly using the “4% rule” from a 1994 paper by William Bengen.

- This used 50/50 equities / bonds portfolio to make it through 30 years of retirement.

- Bengen looked at other asset mixes too but found this was the best blend of growth and safety.

Don worries that with future growth projections (4% real, compared to double that in the past) the real SWR for a 30-year retirement might now be as low as 2.8% pa.

The other problem is that this approach errs on the side of safety.

- In order to make sure that no-one runs out of money, most people using the system will still have a large pot left at the end of 30 years.

- Surely it would be better to eat well, and run the pot down slowly?

Don has a better approach, based on splitting the pot in two.

- One-half starts by aiming at long-term growth, but will be invested in safe assets by the time the other pot runs out.

- This second pot deals with the short-term volatility of equities by being safe from the start.

Don recommends a five-year bond ladder for this second pot though you can also use cash.

- Bonds have the advantage that if they perform well, you can extend the five-year period in which your other pot can grow.

Using a 30-year retirement and a 10-year ladder, Don calculates that the SWR is now 5% pa.

- This assumes the first pot is 50% equities, reducing to all bonds with 20 years to go.

If the growth rate falls to 4% real, the SWR is still 4.2% (using 58% initial equities in the main pot).

Using a 5-year ladder, Don makes the SWR 7% pa (65% initial equity, reducing to zero with 15 years to go).

At 4% real returns, the SWR is 4.4% pa and the initial equity is 78%.

Don recommends re-calibrating the SWR every year, hopefully in an upwards direction.

My own plan is similar to Don’s.

- I’m keeping a five-year cash buffer to ride out bear markets, and the non-property element of my portfolio will start out at around two-thirds equities.

- I’ll aim for an SWR of around 3% (on the non-property bits) and recalculate every year.

I’d settle for a 30-year retirement, but there’s a decent chance that one of us will last 35 or 40 years from here.

- So when my faculties start to fail (hopefully not before age 75), I plan to swap a fair amount of the money into an annuity, which will represent much better value at that age.

Like everyone else, my first priority is to sleep well, but I’d also like to eat as well as the numbers allow.

Objectivity

Have you ever noticed when you’re driving, that anybody slower than you is an idiot, and anyone faster than you is a maniac? – George Carlin

Tim Harford looked at “naive realism“, the idea that we see the world as it truly is, without bias.

- Thomas Gilovich and Lee Ross have a new book out on the topic, called The Wisest One in the Room.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=1780746482]

Carlin’s joke is based on truth – once you decide on the right speed for the conditions, everyone else is wrong.

- You might average out the speeds that everyone has chosen to discover the consensus view, but you don’t.

In fact, whenever we meet people whose views conflict with ours, we assume they are wrong.

The early (1950s) experiments were on football matches.

- I can say from first-hand experience that when I go to a match with someone who supports a different club, we watch separate games.

Follow-up studies have used footage of demonstrations, with the cause changed to suit or conflict with the politics of the subject.

- Not only do people change their view of the acceptability of the protest, they actually see different actions and behaviours.

A third study involved completing a political survey and then explaining your own answers and those of a stranger.

- Subjects believe they are rational, and those with other views are looking for approval (virtue signalling).

- People are tolerant of those with a different cultural upbringing, but still expect them to change.

This feeds nicely into the media coverage of the Brexit referendum, where both sides are claiming bias. ((I have felt that the BBC has a left-wing bias for more than 20 years – back to when I worked there – but I know plenty of people who feel that it’s in the pocket of the government, which is currently Tory. Don’t get me started on Channel 4, or the Evening Standard ))

Brexit brief

Before we look at the “facts” being pushed by both sides, let’s catch up with the regular weekly briefing from the Economist.

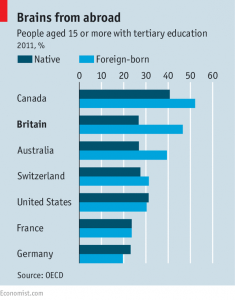

This week it was on immigration, which is apparently the top issue for voters.

- David Cameron promised to bring net migration below 100K pa, but the latest figure was 362K.

- Lots of these people come from the EU, which is why the PM fought to get a four-year delay on in-work benefits for migrants.

But still immigration is the main issue where the Brexit camp is winning.

- Those who worry about immigration want to leave the EU.

Some of the claims are exaggerated.

- Britain has not “lost control of its borders” in the sense most people understand it.

- We aren’t in the Schengen agreement (which appears to be fatally compromised in any case) so we still have passport checks.

But we can’t stop people coming from the EU, which is what the Brexiteers want.

- For them, Britain is full and doesn’t have enough jobs for natives, let alone the foreigners who push down wages and clog housing and other public services.

- There are 3M EU citizens in the UK now, and the Brexiteers want a points system for future immigrants, as in Australia.

- The real question is whether a post-exit Britain could have access to EU markets without allowing free movement.

The scaremongering on the opposite side focuses on the 2M Britons who live in Spain and the rest of Europe.

- No doubt there would be changes to welfare, but these people probably won’t be kicked out.

They also suggest that the refugee camps in Calais might move to Dover, but that treaty has nothing to do with the EU.

The Economist says that immigration is a net economic benefit, and I’m prepared to believe them.

- Assuming the mix of people coming over is biased towards young, healthy workers, it should be.

Immigration is necessary for all maturing countries.

- We don’t want to end up like Japan, with a shrinking population, but even with a points system, that is unlikely.

The real issue is that plenty of people would sacrifice some economic growth for control of their destiny, and those on the other side of the divide can’t quite understand why.

Brexit myths

In the FT, Chris Giles looked closely at some of the “facts” that are flying around. There were five from each side of the fence – I can’t say I’d heard all of these myself:

- We send £18 bn pa to Brussels – net of the rebate, payments are £13 bn, of which £5.9 bn comes back in subsidies and grants. So the final figure is £7.1 bn.

- The EU puts VAT on food – this was actually added by the UK government.

- Criminals can enter Britain under freedom of movement – in fact, people who have served more than a year in prison are barred from the UK, but sometimes the information is not passed to the UK in time.

- We voted for a common market – unfortunately, Thatcher called the EU a “community and alliance of nations” that would work together “for the well-being and betterment of all mankind”

- The EU took our fish catch – over-fishing prior to joining was the real issue, not the reduction afterwards.

- Leaving will cost 3M jobs – this requires heroic assumptions that no serious person would believe (such as all trade with the EU ceasing).

- For every £1 we put in, we get £10 back – this again is based on a prediction of the costs of leaving, rather than real facts today.

- Job vacancies are falling because of Brexit fears – vacancies are down on a quarterly basis (not seasonally adjusted) but up on the same month last year.

- The EU cuts food prices by £200 per household per year – this assumes that EU free trade agreements are not replaced by anything else at all.

- Dozens of premiership footballers would have to leave if we quit – it’s true that EU players get automatic work permits, but the best players qualify anyway through their international appearances.

So lots to argue about, depending on your personal brand of naive realism.

The Economist looked at the enduring appeal of the concept of shareholder value – which we have examined before – through the lens of “Valuation” a 825-page textbook from McKinsey that has sold 700,000 copies. ((I haven’t read it myself ))

The sixth edition was published last year:

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=111887370X]

Shareholders had been in charge of companies in the US since a 1919 court ruling, but the rise of inequality in Western countries over the past 30 years, has given shareholder value a bad name.

- More value for shareholders seems to mean less money for workers.

- And every corporate scandal (Valeant being the latest, but also including Enron, Lehmans, and WorldCom) seems to involve a firm committed to “bringing value to our shareholders”.

The newspaper quite likes the book.

- It developed valuation ideas from the simple PE multiple (ignoring accounting manipulation) to include cash flow, which is harder to fiddle with.

- Corporate projects then needed to generate cash flows above the “risk-adjusted return” required by the providers of the capital.

So a more efficient use of capital meant a more valuable company.

- And outsiders could decide how well managers were doing their job.

This new approach transformed corporate profits from the 1990s onwards, as conglomerates were broken up and unprofitable businesses shut down.

- The change began in the US, then spread to the UK and on to Europe.

- Today it even forms part of Abenomics in Japan and has been adopted by some private Chinese firms (the state-run companies remain unaffected).

The first criticism of shareholder value – that it drives financial engineering with terrible consequences – is not true.

“Valuation” is unrelated to the manipulations, and bad behaviour usually involves breaking its rules.

- Cashflow is king, and leverage boosts risk as well as returns.

- Buybacks don’t create value, they just move it around.

- Only takeovers with synergy will work.

- Earnings per share and the share price are not good targets on which to hang executive rewards.

The second argument – which the newspaper supports but I struggle with – is that the firm should be run for all “stakeholders”.

- In the sense that everybody involved wants the firm to prosper, this should already be the case.

- To further align goals, the workers would have to be the owners – firms would have to become cooperatives (or “Partnerships”, as at John Lewis).

Otherwise, as this week’s row over the closure of the Tata steel plant illustrates, there will always be conflicts.

- Loss-making factories can’t stay open just because it’s best for the short-term needs of the workers.

- That argument was lost forty years ago. ((I have personal experience here, as my father worked in a textile factory that closed when its products were undercut by Asian imports ))

A worker can sell his labour to the highest bidder, and someone with capital can invest in the most attractive prospects.

- A firm that caters to its workers will be less attractive, and a riskier bet.

In the end, the Economist agrees that there is no obvious goal to replace the pursuit of shareholder value.

- I suspect that the rise of AI and robotics will make this ever more the case.

Free trade

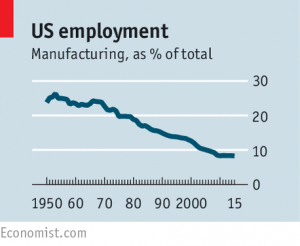

Last week, Tim Harford looked at the benefits and costs of free trade, and this week it’s the Economist’s turn to cover similar ground.

- As we saw, Chinese competition has destroyed US manufacturing jobs.

- More people than expected have not found new jobs nearby or moved away to find work.

- Rising home ownership seems to have anchored people, and many have left the labour force to claim generous disability benefits.

US voters blame free trade for the lost jobs, and in an election year, all the candidates (even Clinton) have backed away from supporting it.

- Yet the cheap imports from China have also had a massive effect on the spending power of the poorest – providing a 62% boost on some estimates.

The newspaper supports free trade, but would like to see more support for displaced workers.

- As it says, new technologies and cheaper robots are just around the corner, and the workforce needs to be able to cope with change.

Until next time.