Weekly Roundup, 30th November 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at analyst recommendations.

Contents

Analyst recommendations

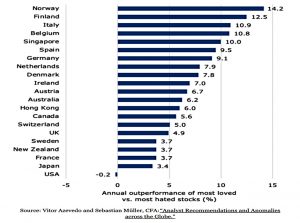

Joachim Klement wrote a piece for the Enterprising Investor blog of the CFA institute suggesting that perhaps analyst recommendations do add value after all.

- A new study suggests that – apart from in the US – the 20% most loved stocks do outperform the 20% most hated.

Here in the UK, the outperformance is just 4.9% pa, but that’s better than nothing.

The study covered 45 countries from 1994 to 2019, covering two big market crashes.

- So the authors were able to compare analyst performance in bull and bear markets.

In a low sentiment phase like that of a bear market or financial crisis, analyst recommendations add more performance than in periods of bullish high sentiment.

Joachim cautions that there are two possible explanations:

Do analysts have deeper insights than most investors and thus are better able to sift through the rubble of a crisis and select the truly good stocks? Or do investors look to analysts for guidance and follow their recommendations more closely during a crisis?

Either way, it’s something that private investors could potentially exploit.

Redistribution

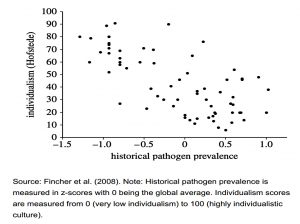

Another of Joachim’s articles looked at the impact of the historical prevalence of pathogens on the degree to which a society is individualistic.

- I’ll cover that in more detail if/when I next write about the coronavirus.

The article also contained an interesting observation about attitudes to redistribution.

- It turns out that strong (rich) men are more opposed to redistribution than (weak) rich men.

This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective.

- Strong men would historically not have conceded assets to week men.

Interestingly, strong poor men are keener on redistribution than weak poor men.

- They would historically have taken assets from weak rich men.

In summary, stronger men act more selfishly because they can.

Makes sense to me.

The Great Reset

In his weekly newsletter, John Mauldin had some worrying thoughts about his version of “The Great Reset“.

- The phrase has recently been adopted by the World Economic Forum (the Davos gang) to mean something very different.

To achieve a better outcome, the world must act jointly and swiftly to revamp all aspects of our societies and economies, from education to social contracts and working conditions. Every country, from the United States to China, must participate, and every industry, from oil and gas to tech, must be transformed. In short, we need a “Great Reset” of capitalism – Klaus Schwab, WEF.

Which is worrying enough in itself.

For John, the problem is “too many elites”. He quotes Peter Turchin, a zoologist who applied theories of how beetle populations work to human society:

One way for a ruling class to grow is biologically—think of Saudi Arabia, where princes and princesses are born faster than royal roles can be created for them. In the United States, elites overproduce themselves through economic and educational upward mobility: More and more people get rich, and more and more get educated.

The problems begin when money and Harvard degrees become like royal titles in Saudi Arabia. If lots of people have them, but only some have real power, the ones who don’t have power eventually turn on the ones who do.

Elite jobs do not multiply as fast as elites do.

The end game is state insolvency, but the antepenultimate and penultimate steps are handouts and freebies to pacify the population, and then oppression to police dissent.

- Judging by world politics over the last decade – and the response to Covid-19, we seem to have reached the freebies stage.

Which racks up debt, which must eventually be dealt with.

Turchin identifies 50-year cycles of social instability, which John equates to human generation turnover.

- And the youth bulge of the 2020s could be the catalyst (as the Boomer bulge was in the 1970s).

Going back to the debt, John quotes Bill Dudly on the four ways of dealing with it:

One: Households, corporations and governments try to save more to repay their debt. This gets you into the Keynesian Paradox of Thrift, where the economy collapses.

Two: You can try to grow your way out of a debt overhang, but a debt overhang impedes real economic growth.

This leaves the two remaining ways: Higher nominal growth – i.e., higher inflation – or restructuring and [write-off].

So inflation and/or write-offs seem plausible, though who knows when.

Multi-factor funds

In the FT, Steve Johnson reported that multi-factor funds have fallen from favour.

- More have closed than have opened during 2020, the first year this has happened since the sector was created 17 years ago.

Assets in the funds – which account for between 4% and 6% of the smart beta sector – have slipped from $69.3 bn to $65 bn.

- Only 16% of funds have beaten their benchmark over the five years to August 2015. (( I would not expect the majority of smart-beta funds to beat their benchmark ))

The underperformance of multi-factor funds is mostly down to the decade-long underperformance of value investing, the worst such run for 200 years.

- Small caps have also underperformed relative to the giant tech growth leaders.

Shrinkage was concentrated in the US, which could have reached a saturation point.

- New markets like China are still showing strong growth.

There’s also a split between retail investors, with whom the funds are less popular, and institutional investors who remain keen.

Asset management

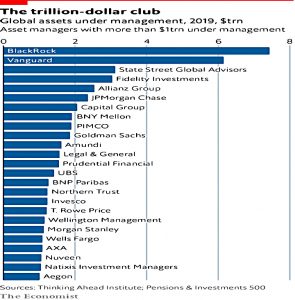

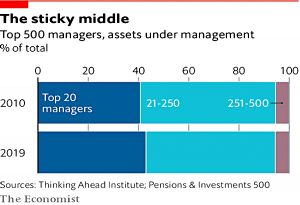

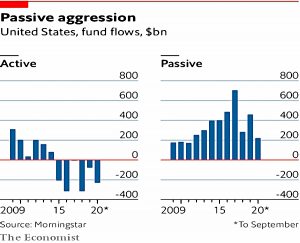

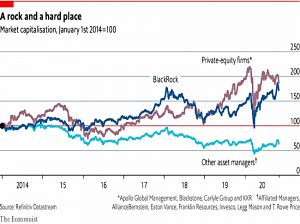

The Economist featured an eight-part special report on asset management.

It is a business unlike any other. Managers charge a fixed fee on the assets they manage, but customers ultimately bear the full costs of investments that sour.

For all the talk of pressure on fees, typical operating margins are well over 30%. Yet despite recent consolidation, asset management is a fragmented industry, with no obvious exploitation of market power.

Firms compete in marketing, in dreaming up new products and, above all, on their skill in selecting securities that will rise in value.

This is despite the fact that active funds underperform in aggregate, a fact known since 1968.

It is hard to find a positive link between high fees and performance. One study found that the worst-performing funds charge the most.

Which is not surprising, since the average performance should be the benchmark minus the average fee.

One explanation is that funds are “credence goods” – since consumers can’t distinguish between a good one and a bad one, investors choose “hot” funds.

- Once gathered, assets are sticky and only slowly worn away by poor performance.

A [2015] paper argued that fund managers act as “Money Doctors”. Most people have little idea how to invest, just as they have little idea how to treat health problems. A lot of advice doctors give is generic and self-serving, but patients still value it.

The money doctors are in the same hand-holding business. Their job is to give people the confidence to take on investment risk.

Fair enough, but they would save a lot of money if they could develop that confidence by themselves.

- The move to passive funds suggests that they – and particularly younger investors – are finally getting the message.

Topic covered in the report include:

- How indexing is reshaping the industry

- The agency problem of delegating your investment choices

- The lack of oversight of company managers when investors and asset managers merely track an index

- Private markets – niche, illiquid and fee-rich

- Venture capital – more money chasing fewer ideas

- Asset management in China

- The future of asset management.

Quick links

I have just two for you this week:

- Jesse Felder explained that sentiment is now more euphoric than at the peak of dot com mania

- The Economist wondered whether big firms will benefit from the covid crunch.

Until next time.