Becoming a Lloyd’s Name

Today’s post is about whether it’s a good idea to become a Lloyd’s Name.

What’s in a Name?

Or rather, what is a Name?

A Name is a private investor in the Lloyd’s of London insurance market, which specialises in reinsurance – sharing in the risks of business generated elsewhere.

- As you might imagine, reinsurance is most useful where the risks are large – in so-called catastrophe insurance, for example.

Lloyds dates back to 1688 and has never failed to pay a claim.

It includes corporate as well as individual members.

- Members are also known as capital providers.

The individual members are the Names.

- Technically, Names are individuals that have unlimited liability (see below).

Corporates can be companies or Limited Liability Partnerships. (( At the time of writing, three of the corporates were listed: Hiscox (LON:HSX), Lancashire (LON:LRE) and Beazley (LON:BEZ) ))

Names and corporates operate together through syndicates run by managing agents.

- Members of syndicates are severally (not jointly) responsible for their own share of the syndicate’s profits or losses.

Why?

The big attraction of being a name is the ability to use capital twice.

- You stake (for example) a share portfolio as collateral against the risks you insure.

- If the underwriting team does its job, premiums exceed liabilities and you make a profit for the year.

- And you still have the returns from your share portfolio.

This is one of the secrets to Warren Buffett’s great wealth – at its heart, Berkshire Hathaway is an insurance company.

It’s another form of leverage, but under normal circumstances, it’s free leverage.

- You could borrow money to buy shares in insurance companies, but you would need to pay interest on the loan.

Imagine if you could borrow money to invest for free – that’s what being an insurance underwriter is like.

- It’s the difference between being the gambler in the betting shop and being the bookmaker.

The other advantage is diversification:

- Returns will have a low correlation to those from stocks and property.

Lloyd’s profits follow the underwriting cycles, which is driven by capital in the market:

- When syndicates’ profits rise, more capital flows in, premiums drop and underwriters make less money – this is called a soft market.

- Underwriters then cut back the amount of business they will take on, rates tighten up and profits rise – this is a hard market.

Cycles typically last five to seven years.

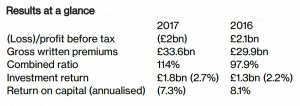

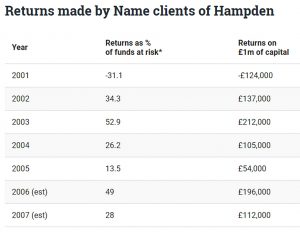

Getting hold of real return figures is not easy.

- The table below is out of date, but it does illustrate the year-to-year volatility.

A recent article in the Spectator reported that the average return at Hampden from 2001 to 2016 was 11% pa.

Note that Lloyd’s accounting works on a three-year cycle, and a year of profits may be retained to pay for any loss in the following year.

There can also be tax-planning advantages of operating through a Nameco.

- And HMRC considers underwriting to be a trade rather than an investment.

So it is eligible for Business Property Relief (BPR, which includes IHT exemption) and Entrepreneurs’ Relief.

Why not?

The main reason that most people in the UK would run a mile when asked whether they would like to be a Name is that they remember 1988.

- After a long run of profits that attracted a lot of new Names, five years of losses totalling £8bn (mostly from US asbestos and other pollution claims) hit the market.

- The average loss at the time was £287K.

Although Names are anonymous, it became a trendy thing for the rich and famous to do in the 1970s and 80s (there were also tax advantages at the time).

- Numbers rose from 8,000 in 19975 to 34,000 in the 1990s.

Some of the Names were under the impression that Reinsurance to Close (RITC) cover meant that their liabilities ended at the close of each underwriting year.

- 200 Names sued Lloyds and the court cases dragged on for years.

Many Names were ruined and some were bankrupted.

- More than a dozen committed suicide.

Limited liability

At the time of the crisis, the liabilities of Names were unlimited – all of their assets and net worth were at stake.

Following the crisis, all of the pre-1993 liabilities were ring-fenced into a “bad debts” run-off company called Equitas.

- This firm paid out more than $30bn in claims.

- Eventually (in 2007) Equitas was sold to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway.

Since 1998, Names have operated under a limited liability system (like company directors and shareholders), so this could never happen again.

- Individuals – and groups of connected individuals – now operate through “Namecos”.

- There are also similar Group Conversion Vehicles for groups working together.

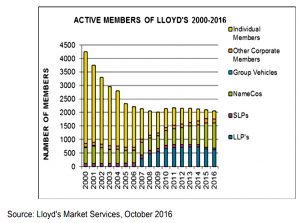

There are far fewer individual Names these days (around 2,000), and the vast majority of funds are corporate in some sense.

- Individuals now contribute just 9% of underwriting capacity.

But Lloyd’s likes private capital because rating agencies like S&P score Lloyd’s on the variety of its capital.

How?

The joining process starts with finding a friendly managing agent to explain the technicalities.

- Then it takes up to six months for Lloyds to check your finances.

During this period you can form your Limited Liability Vehicle (LLV or Nameco).

- Or you could buy into an existing one.

Next, you have to choose a syndicate (based on the declared levels of risk and target returns).

- Then you have to buy into it, via a closed auction (sealed bids).

How do I leave?

Most Names stay, but you can sell your Nameco (and its attached underwriting) at any time.

- The price depends on the number of buyers willing to bid.

If you are in a hurry to leave, the price is likely to be lower.

- And after a loss-making year, you might not be able to sell at all.

After a few years, the growing reserves of your syndicate should mean that you make a profit.

How much?

Here’s the rub – you need a minimum of £600K to £850K to become a name.

- The minimum insurance capacity that you can provide is a cool £1M.

- The minimum collateral you need to put up was 40% (£400K), but appears to have increased to 50% (£500K).

You also need £200K to £350K to buy a stake in a syndicate.

- As noted above, this can be resold, potentially – in the long term – at a profit.

In a bad year, you might lose £150K of your £1M exposure.

- You’d then need to find that amount to top up your collateral.

More volatile syndicates might make a “cash call” on a quarterly basis.

Clearly, a £500K share portfolio and £200K of cash will be technically possible for many.

- There are more than 800,000 millionaire households in the UK.

- But most of these will be people with nice houses in London and the South East.

And then there is diversification to think of.

- You might want to limit your exposure to reinsurance to say 10% of your net worth.

Which means that you need £10M to play.

- And cover the impact of a bad year, perhaps £12M.

It’s a nice idea, but perhaps not this week.

Until next time.