Weekly Roundup, 20th July 2015

The Grexit saga drags on. The rescue plan has been approved by the Greek parliament, the Greek banks have reopened and VAT has been increased on many goods and services. We await approval of the plan by the other governments involved (thankfully not our own).

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with Merryn’s column in the FT.

Contents

Debt vs Equity

Merryn was choosing some books to read on her holiday. In the light of the Summer Budget’s withdrawal of higher rate income tax relief on buy-to-let mortgage interest, the one that caught my eye was Debtonator by Andrew McNally.

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=B011T8LHDA&text=Debtonator&template=thumbnail]

McNally thinks that the tax advantages of debt over equity lead to instability and inequality. Today’s low interest rates only compound the tax advantages.

When bad times hit, companies (and countries) with debt generally don’t survive. But even in the good times, companies with debt are less likely to invest in people or equipment, to write off old assets, and to experiment generally.

And the preference for raising new debt to fund expansion over issuing new equity locks outsiders away from the greatest source of wealth creation. This in turn concentrates wealth amongst the already haves.

I’m increasingly convinced that removing the advantages of debt for all businesses would be a good idea.

Income investing

Terry Smith wrote about the desperate search for income – we’ve reached the stage where Italian 10-year government bonds yield less than 1.5% pa.

In fund management, putting “income” in the name of a fund is one of the best marketing tools available, since investors are desperate for it. But lots of income funds are falling out of the income sector classification.

To stay in they need to produce 110% of the All-Share yield over 3 years. The Invesco Perpetual Income and High Income funds are two high-profile casualties.

Not that you’d know, since they are allowed to retain the Income label in their name even if they don’t qualify. Even worse, a new fund gets three years to prove they can deliver the required yield before being kicked out of the sector (in which time they hope to have picked up sufficient assets to be viable).

Terry went back to the quote from Jack Bogle that sums up the desire for income: “Over the past 81 years [to 2007] reinvested dividend income accounted for approximately 95% of the compound long-term return earned by the companies in the S&P 500.”

The key word here is reinvested. Looked at from the opposite perspective, if you spend the income, you are giving up 95% of the returns (over 81 years, which is admittedly too long a time-horizon for most).

Terry also points out that Bogle was using the index as the base. He believes that investing in companies with a return superior to the index is preferable to simply re-investing your dividends. He gives Berkshire Hathaway – which has never paid a dividend – as an example. Return on investment is the real driver.

I agree with Terry, but I suspect he is rather better than me at identifying in advance the companies that will deliver superior returns. I would also point out that competing strategies (eg. reinvested income vs. superior return on investment) tend to perform well at different times.

It is for these two reasons that I will follow both strategies, and several others besides.

Apple Pay

The FT had two articles – both Q&As – on the arrival of Apple Pay in the UK, its first launch outside the US.

Lucy Warwick-Ching was first:

- users of iPhones, iPads and Apple Watches can pay bills of up to £20 at 250K shops and restaurants, plus Transport for London (underground, buses and trains); retailers include M&S, Boots and lots of fast food outlets and coffee shops ((If your phone runs out of battery during a journey, you risk an £80 fine if you meet an inspector))

- you can add a bank card to the Wallet app using the 3-digit security code (if your Apple account already knows about the card) or you can scan a card (or even add it manually); you can add as many cards as you like

- before you can use a card, you need to verify with your bank (either by text or voice call)

- when you are near a payment terminal, you use fingerprint technology – supposedly safer than chip & pin- to identify yourself, then tap your device against the card reader; the device vibrates to confirm the transaction

- Santander, Nationwide and RBS (NatWest) launched this week; Barclays, Lloyds, Halifax etc. will join later this year

John McDermott answered (and asked) some slightly different questions:

- Since the UK already has contactless payment cards, all this means is you can tap your phone against the reader instead of your card.

- Given the minority share of the UK phone market that Apple has, is this three-second advantage really a game changer? Perhaps, for Apple fans (who probably make up a lot of the people who want to contactlessly pay for a flat white).

- It might also reduce the “pain of paying” – cards already feel less like money than cash; maybe a phone will feel less like money than a card. ((This is why gambling in casinos uses chips – plastic toy money))

Higher rate tax

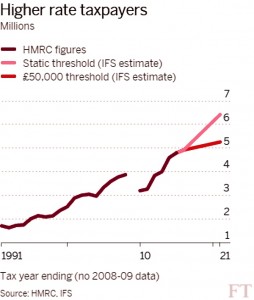

Adam Palin looked at the pledge in the Summer Budget to take “hardworking people” out of the higher rate income tax band by raising the threshold.

The bad news is that wage inflation over the next five years means that even more people will be paying the higher rate by 2020. This is using the government’s own figures, from the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Osborne has said he will increase the threshold from the existing £42.4K up to £50K by 2020 – an increase of 18%. Unfortunately wages will rise by 24% in the same period.

An extra 340K taxpayers will be fiscally dragged into the high rate band, taking the total to 5.3M, up from less than 2M twenty-five years ago.

The last five years have been particularly bad, as the higher rate threshold was frozen and then reduced to compensate for the rapid increase in the tax-free personal allowance.

It should also be noted that the savings in income tax (20% vs 40%) are offset by increases in NICs (up from 2% in the higher rate to 12% on income falling in the standard rate). True tax rates for workers are 32% and 42%, not 20% and 40%.

Public sector pension liabilities

Neil Collins reported on the victory of a fireman who took the Strathclyde fire brigade ((More specifically, the Government Actuary’s Department – GAD – who calculated the pension entitlement)) to the pensions ombudsman. Having retired aged 50 after 30 years service, his pension pot was assessed as £444K.

In fact it was around £470K, of which his contributions (at between 11% and 13% pa, much higher than most people) totalled £40K.

The noise around the ombudsman’s decision has been that it will cost taxpayers an extra £860M in pension payments to firemen and policemen.

But the real problem is that the vast majority of every public sector defined benefit pension pot comes from us.

Retiring at 50 with a massive pension pot (relative to annual salary) has got to go. Public sector DB pensions have to go.

Value versus growth

Lex looked at the changing fortunes of Provident Financial (PF) and International Personal Finance (IPF):

- IPF was demerged from PF in 2007

- IPF makes short-term consumer loans in eastern Europe and Mexico, and was seen as a growth stock

- PF was seen as a dull yield stock

Since the demerger, IPF has doubled revenue and outperformed the FTSE 250. But it fell this week as Poland threatened to cap charges.

PF has done even better, mostly by issuing credit cards to people with flawed records. The traditional door-to-door home-credit business is now less than one-third of revenue.

After almost catching up with PF in terms of market cap, IPF is now worth only a quarter as much.

The alchemist fallacy

Tim Harford looked at the alchemist fallacy, which is the idea that if a method were to be found for cheaply turning lead into gold, then gold would still remain precious.

Tim uses the example of glass to show how things would work. In ancient times, naturally occurring glass could be quarried but not made. It was so precious it was used for Tutankhamun’s jewellery.

Then someone worked out how to make glass from sand. For a while the Venetians guarded the secret, but it leaked, and now glass is so cheap that we can use is as packaging for water (amongst many other things).

A few years ago William Nordhaus tried to work out what proportion of the social gains from an innovation the innovator is able to hang on to. He pointed out after the dot-com crash that the boom valuations of such companies implied that 90% of gains could be retained. ((Somehow, Apple appears to have managed this with their geegaws))

Nordhaus estimated that in fact only 3.7% of gains from 1948 to 2001 were retained by innovators. Consumers received the majority of the remainder.

What the right figure should be for society depends on what kind of innovation we need. If retention is too high, the benefits of new ideas spreads too slowly.

When it is too low, only those who create for love will innovate. This might work for art, but not for medicine or high-end technology.

On the other hand, patent and copyright laws appear to currently offer too much protection to “inventions” that would have happened anyway.

Inequality

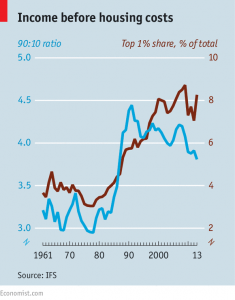

The Economist looked at whether UK inequality is rising or falling? The short answer is both, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

A big gap between rich and poor opened up in the 1980s, but since the early 1990s is has closed again. This “90:10 ratio” between the income of the top 10% and the bottom 10% is not at its lowest for 25%.

But the top 1% are pulling ever further ahead, and now receive more than double the share they did 30 years ago.

Housing and productivity

The newspaper also looked at whether stalled productivity in the UK is linked to the lack of housing. Britain’s productivity (output per hour) is flat since 2007, while in the US it is up 9%. It’s holding back wage growth.

Rather than invest in education, health and technology, the government plans to attack it through housing.

Britain needs 250K new homes a year but built only 150K last year. To change this, the chancellor has announced:

- automatic planning permission on brownfield sites

- automatic permission for homeowners to extend upwards to the height of adjacent buildings

- high-density housing around transport hubs

- penalties for local authorities that fail to make decisions “on time”

This could boost productivity, especially around London.

The capital is by far the most productive part of the country, thanks to finance and technology. One third of the 2M jobs created in Britain since the recession are here, but more housing would mean even more:

- the average London house costs £370K, almost double the national average

- the ratio of prices to earnings exceeds 20:1 in some places

- but the number of homes has increased by only 9% in a decade

- people per property rose from 2.3 to 2.5 over the same period

- the number of people wasting time (and a potential £12bn in productivity) on commuting into the capital rose by 32%

Working against Osborne’s measures are the proposals to cut social rents by 1% a year for the next four years. This will cut supply by making new social housing less attractive to build.

And Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners (NLP), estimate that only 1M houses can be built on brownfield sites. That’s just four years’ supply. At least three times as many homes will be needed in the next 15 years. The green belt may have to be tightened.

The threat to the City

The future of the City – and the hundreds of thousands of jobs it sustains – is a perennial topic of discussion, and the Economist gave the matter another airing. ((Disclosure: this is a subject close to my heart as it formed the basis of my MBA dissertation more than 20 years ago))

Bankers in London regularly threaten to decamp to Switzerland in the face of high taxes and unsympathetic regulation, just as those in Geneva threaten to move in the opposite direction.

Recently there have been three complaints:

- the new tax on banks profits

- London property prices

- the possibility of Brexit following an EU referendum

The City is doing well. Around 8% of Britain’s economic output comes from finance, and it generates net exports of $95 bn. Only New York (bigger but less international) is a rival.

It has several enduring competitive advantages:

- the trading day links that in Asia to that in North America

- it has a well-educated English-speaking workforce, including lawyers, accountants and business consultants

- it has a popular system of common law

- the UK is an open trading nation

- London is more exciting to live in than Frankfurt or Singapore

Also, other potential replacements have flaws:

- New York is too domestic and can’t cover Asia

- Frankfurt is too small, as a city and a pool or talent

- Paris exists under a government hostile to banking

- Geneva (according to returning traders from Brevan Howard) is dull

- Hong Kong is too small

- Shanghai suffers from the difficulty of moving money in and out of China

- Singapore is still focussed (for now) on becoming a regional rather than a global centre

But there are precedents for business leaving the City:

- some insurance has move Bermuda and similar tropical islands

- fund-management is centred around Dublin and Luxembourg

- private-banking is based in Switzerland

- back offices and IT have moved outside London

The bank levy (a tax on balance sheets) has been halved recently and will now apply only to local operations. The idea is to prevent HSBC and Standard Chartered from moving to Asia.

But it still makes government bond trading (low risk, but balance sheet inflating) expensive. Processing will be moved to more tax-friendly locations, and bodies will inevitably follow in time.

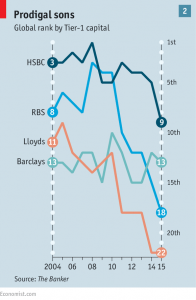

Bond and FX trading have both been shrinking since the financial crisis, though it is not clear why. The British banks have also become smaller in recent years.

There have also been trading scandals in recent times:

- LIBOR (a benchmark interest rate) and FX markets were rigged

- JP Morgan lost $6 bn to the “London Whale”

- US regulators have even blamed the 2010 US “flash crash” a London day trader

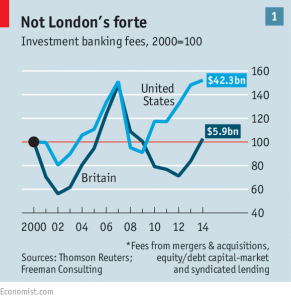

The other parts of investment banking – issuing debt and equity and M&A activity – are smaller in London than the US, since bank finance has been more common.

As banks are displaced in this by asset managers, insurers, sovereign-wealth funds and other “buy-side” firms, the ties of this trade to London are weakened.

Commodities are an example: regulation forced many of the banks to devolve these units to the buy-side. Soon after they migrated to Switzerland.

The big threat remains Brexit. City bosses don’t want to lose “passporting” rights which allow a firm to do business throughout the EU while being supervised only by British regulators. ((It works in the opposite way, as private investors trading through firms regulated in Cyprus may already know))

Since France and Germany are no friends to the City, negotiating an exit which retained passporting is unlikely. The UK would be seen as an offshore financial centre.

Attracting employees from the EU would also be difficult. Work permits for those outside Europe are already an issue.

One bright spot (for those in the City at least) would be the removal of the cap on bankers’ pay.

Perhaps the only other one is that Brexit seems unlikely at present. But a lot can change in two years.

Until next time.

Thanks for another excellent roundup of links Mike. Keep up the good work…

John