How I Invest 1

Today’s post is our first visit to a new book – How I Invest My Money by Joshua Brown and Brian Portnoy (illustrated by Carl Richards of Behaviour Gap cartoons fame).

Contents

How I Invest My Money

I’ve been looking forward to reading this book for a while, not only because I pre-ordered it a couple of months before it was released.

- I pitched a similar idea – but based on UK rather than US investors – to the publishers (Harriman House) a couple of years ago.

Of course, I don’t have the profile of Josh Brown, the Reformed Broker blogger – and a book about US investors will no doubt have much wider appeal.

I’ve long subscribed to Taleb’s maxim that people shouldn’t tell me what they think, they should show me what’s in their portfolio.

Not surprisingly, few people seem to want to do that, but I’m hoping this book is the exception. (( For disclosure, I report my own holdings once a month on this website, but only at an aggregate level; if you read the entire blog, however, you would have a pretty good idea of where my money is ))

Of course, they might all just say that they dollar-cost-average into Vanguard index funds.

- We shall see.

Introduction

Josh has been on financial TV in the States for close to ten years now, with an average of three shows a week.

- In all those 1,400 hours of TV, nobody asked him what he does with his own money.

So he wrote a blog post about it, which I remember reading.

- And now he’s turned it into a book.

He’s asked around 25 industry professionals to explain how they manage their own portfolios.

More important than the “how” is the “why.” All of the people in this volume are well-versed in academic investing theories. But as you’ll see, everyone is coming from somewhere unique.

Josh tells a story about one of the big index fund providers confiding in him that lots of hedge fund managers kept their own money in index funds. Josh was not surprised.

Elaborately allocated and expertly traded portfolios are the quickest route to being able to charge enormous fees. But are they the best solution for those seeking reliable growth and some degree of long-term certainty for their financial futures?

It made perfect sense to me that people who were already extraordinarily wealthy would want to preserve their wealth using a method very far away from the strategies they use in their professional lives.

This is slightly worrying to me – I hope we aren’t in for 25 versions of “I invest in index funds.” (( More disclosure: around 40% of my own wealth is in index funds – but not 100% ))

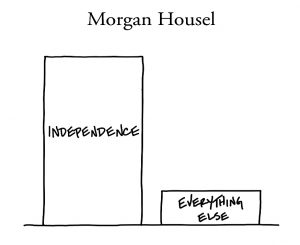

Morgan Housel

Morgan Housel is a partner at the Collaborative Fund and a prolific finance writer, speaker and blogger.

- He recently published The Psychology of Money, which we will cover on this website at some point in the future.

Morgan quotes Sandy Gottesman, the billionaire founder of First Manhattan, in the same vein that I quoted Taleb earlier:

What do you own, and why?”

This is apparently one of his interview questions.

Half of all US mutual fund portfolio managers do not invest a cent of their own money in their funds, according to Morningstar.

Morgan points out that doctors share the same hypocrisy:

Ken Murray wrote an essay called “How Doctors Die” that showed the degree to which doctors choose different end-of-life treatments for themselves than they recommend for their patients.

They opt for less treatment. Morgan doesn’t think this is a bad thing:

When dealing with complicated and emotional issues that affect you and your family, there is no one right answer. ere is no universal truth. There’s only what works for you and your family.

Up to a point – as Morgan concedes, there are “basic principles that must be adhered to”. For him:

Independence has always been my personal financial goal. Independence, at any income level, is driven by your savings rate. And past a certain level of income, your savings rate is driven by your ability to keep your lifestyle expectations from running away.

So far, so good: Pay Yourself First, and Don’t Keep Up With The Joneses.

- This not only makes financial sense, but it removes a lot of psychological pressure.

Morgan still lives below his means.

It’s not that our aspirations are nonexistent – we like nice stuff and live comfortably. We just got the goalpost to stop moving.

Morgan has also paid off his mortgage, even when interest rates were low, for peace of mind and independence.

- I agree and did the same thing quite a while back.

He also keeps more cash than most would recommend – 20% of the portfolio excluding the house.

- I’m at less than 10% on that score myself.

Everyone – without exception – will eventually face a huge expense they did not expect.

On to investing:

I started my career as a stock picker. We only owned individual stocks, mostly large companies like Berkshire Hathaway and Procter & Gamble, mixed with smaller stocks I considered deep value investments. Now every stock we own is a low-cost index fund.

I think some people can outperform the market averages – it’s just very hard, and harder than most people think. For most investors, dollar-cost averaging into a low-cost index fund will provide the highest odds of long-term success.

Oh dear. My worry is that the book is stuffed with busy, high-profile finance professionals who need to devote more time to marketing than to clever investing.

Morgan has some nice things to say about active investors and some criticism of how index investors assess the odds in other areas of life.

- But this book is about what people do, not what they say.

And Morgan invests in index funds.

We invest money from every paycheck into these index funds – a combination of US and international stocks. We max out retirement accounts in the same funds, and contribute to our kids’ 529 college savings plans.

All of our net worth is a house, a checking account, and some Vanguard index funds.

My investing strategy doesn’t rely on picking the right sector, or timing the next recession. It relies on a high savings rate, patience, and optimism that the global economy will create value over the next several decades.

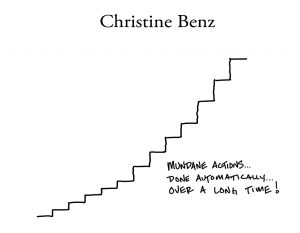

Christine Benz

Christine Benz is Director of Personal Finance for Morningstar and has written several books.

We’re off to a bad start with Christine:

I’ll never be passionate about investments. What I am passionate about is investors, and most of them aren’t passionate about investments, either.

Rather, they view investments as a means to an end. A streamlined, low-cost, and utilitarian portfolio is the way to go.

Christine and her husband each have 401(k)s (employer pension accounts), plus IRAs (a cross between ISAs and SIPPs) and taxable accounts with Vanguard.

Within my Morningstar 401(k), I have both active and passive funds, but mainly active. My account is primarily equities. I steer a fourth of my contribution into four equity funds: Vanguard Institutional Index, American Funds Washington Mutual, Vanguard International Growth, and Dodge & Cox International.

My husband’s 401(k) is mostly all passive, though his bond exposure is PIMCO Total Return. He has a bit more in bonds in his 401(k) than I do. We hold our taxable assets at Vanguard; we have money that goes in on autopilot every month. We just have a few funds: Vanguard Primecap Core, Developed Markets Index, Intermediate-Term Tax-Exempt, and Tax-Exempt Money Market.

I’m afraid it’s another boring chapter – Vanguard index funds again, plus a bit of detail on how best to cope with the US tax system.

If we have made mistakes, the main issue would be that we always have quite a bit of cash knocking around in our taxable account mainly because of inertia and because it never feels like a great time to move it all into something with more return potential.

On the other hand, knowing that we have liquid reserves that we could tap in a pinch probably gives us peace of mind to stay very aggressive with our retirement accounts.

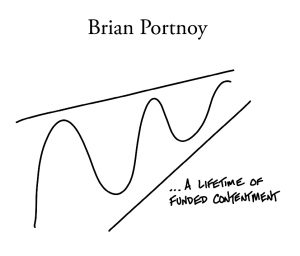

Brian Portnoy

Brian Portnoy is Josh’s co-author, and the founder of Shaping Wealth, a “financial wellness platform”.

- He’s also written two books on behavioural finance.

True wealth, I believe, is the ability to underwrite a life that is meaningful to me.

He calls this funded contentment.

What we need for retirement is a guess, so we’re maxing out 401(k)s and IRAs. The third goal [after college fees] is to leave the kids without the financial burden of caring for me and Tracy. Helping to support my mom is unpleasant.

Brian also helps to support a developmentally disabled sister.

Tracy and I have been disciplined in our spending because we just don’t covet the big-ticket items (cars, jewellery, wine, art, fancy travel) that seem to seduce others. We paid off our mortgage a while ago. I love not having a mortgage, and no other debt to speak of.

So the saving story is the usual one – live within your means, save and have no debt.

- On to investing.

I have four buckets: 1. Free beta 2. Juicy cash 3. Enterprise income 4. Long-term options

The free beta is once again a Vanguard index fund – Total World Stock ETF (VT).

I have zero interest in actively tilting my portfolio by region or sector or other factors.

Juicy cash is too much cash – 25% at times. Brian justifies this by linking his career prospects to market beta. He parks the cash in municipal bonds yielding 5%, which are not available in the UK.

- Of course, strictly this is bond investing, not cash.

The “enterprise income” is mostly property rentals, plus short-term private loans – property and small business – that he accesses through his private investor networks.

Long-term options are angel and venture capital investments.

If a few of these hit, I will make “a lot” of money. The actual number is a total guess and to peg my financial plan on one would be foolish. These are lottery tickets.

Brian’s plan turned out to be a little more interesting, but private loans and angel investment are out of reach to most private investors.

- And tax-advantaged muni bonds don’t exist in the UK.

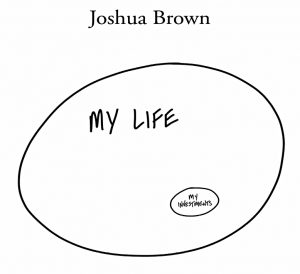

Joshua Brown

“Downtown” Josh Brown is the co-founder and CEO of Ritholtz Wealth Management and writes the Reformed Broker blog.

- He also contributes to CNBC TV.

I’m a mixture of active and passive, a mixture of mutual funds, individual securities and ETFs, a mixture of public and private assets. What is consistent is that almost everything I do is with a long-term bias.

As Josh points out, short-term trading is difficult and time-consuming.

He also has a property:

The bulk of my net worth is in my house, with no mortgage. We intend to live there forever.

And a private business:

My other big investment is the 30-something percent I own of Ritholtz Wealth Management (RWM).

Now for some good news:

My [company] 401(k) is invested in the exact same asset allocation model as we use for our clients. I own the same funds, in the same proportions, that my clients of comparable risk tolerance own.

That model is all equities since Josh is 25 years from investment. He also has individual stocks and ETFs in tax-deferred accounts (analogous to UK SIPPs).

Mostly companies where I am a fan, user and customer of their products and services. JPMorgan, Slack, Starbucks, Shake Shack, Apple, Amazon, Google, Verizon, Uber, etc. I buy these things and don’t sell them. I automatically reinvest the dividends.

He also holds REITs in these accounts, where the mandatory distributions are tax-sheltered.

But he doesn’t believe in alpha.

I just love stocks and have ever since I was 20 years old. And it’s my money.

He also has child college funds (529 plans) in Vanguard index funds and more money for the kids in a robo-advisor called Liftoff, which is fronted by RWM in partnership with Betterment.

- And he also invests in startups, often using the EquityZen platform.

I prefer to be involved with companies whose products or services I actually use. There’s no such thing as “free” in this world, and being offered stock in a fintech startup is no different.

Josh won’t get into arguments about portfolio construction.

If you’re confident in what you’re doing, then the last thing in the world you’re worried about is what other people are doing. I literally could not care less what other people think. When people disagree with you there’s a very simple way to resolve the conflict – time. If you’re so smart and I’m so dumb, then you’ll make a lot of money betting against me.

Josh is a good writer, but it’s another boring portfolio – index funds, no debts, a bit of VC.

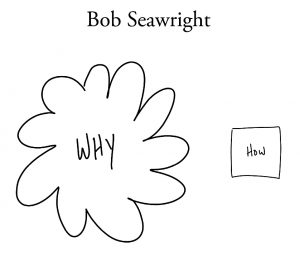

Bob Seawright

Robert Seawright is CIO for Madison Avenue Securities, an investment advisory firm.

Bob begins with a story about his dying mother-in-law and the great investment that her country cottage proved to be over her lifetime.

- The point is that we should spend more time on why we invest, not just how we invest.

Unfortunately, this book is called “How I Invest”.

I am confident every contributor to this book offers similar investment strategies: simplicity; aggressive saving; a balanced lifestyle; diversification; low costs; a sensible asset allocation consistent with one’s goals, risk capacity, and risk tolerance; smart asset location; careful tax/estate planning and management; and a focus on the power of compound interest.

Bob and his wife now also have a country cottage, which is a “lousy investment”.

Because we live in Southern California and have owned our home for the 25 years we have lived there, we are already overweighted in real estate. Property taxes are high. It requires significant upkeep because the winters are hard and the buildings old. It’s only useable in the summer and cannot practically be upgraded for year-round use.

But:

It’s the most important financial investment we’ll ever make.

In a footnote, Bob explains a little more about his actual investments:

Because Ginny is a teacher, she has a 403(b) and a good pension. I have a 401(k) and we have a joint investment account. We invest in low-cost, globally diversified funds. We own no individual stocks and no derivatives. We rebalance automatically.

We overweight foreign stocks because of the better values available there, but recognize that bet may not pay off. Because Ginny’s pension and my Social Security will cover our expected living expenses in retirement, we have a much lower exposure to bonds than is typical for people our age.

If not he would use an annuity for guaranteed income (!).

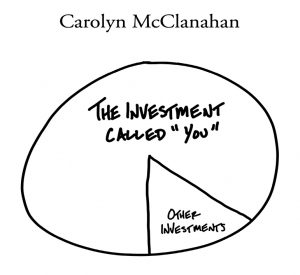

Carolyn McClanahan

Carolyn McClanahan is a doctor and the founder of Life Planning Partners, a financial planning company.

In residency in the early ’90s is when I learned about investing. Everyone was into “hot stocks” and trying to beat the market. I met my future husband in 1996. He was an engineer, an only child, and his parents had recently died and he received an inheritance.

I helped him invest that money and we did well. Little did I know–we were just lucky. By 1999, I thought I knew it all. In addition to practising emergency medicine, I day traded stocks on the side.

Carolyn lost money in the dot com crash, but they paid off their mortgage.

- She switched careers to become a financial planner.

I learned the most important determinant of financial independence was not how much you save – it is how much you spend. I became a convert of diversification and investing for the long term.

But she still used active funds until the 2008 crash.

2009 threw me over the fence into the passive camp. Why? All those great “bear market funds” tanked worse than the rest!

Carolyn’s money is now managed by one of the CFAs in her firm.

The allocation is 50% fixed income and 50% equities, and we use all the same funds as our clients. We just keep socking money away and track our spending year to year.

Her advice is:

Invest in yourself. Your ability to work is your safest and highest returning asset.

Conclusions

Oh, dear.

I’ve been waiting months to read this book and it’s a damp squib – lots of life stories, low key ads for services people offer or are connected with, and (mostly) the same boring message:

- index funds, no mortgage, a bit of VC and some private loans.

Not exactly rocket science.

- It would be fine if the book were called “How I feel about money”, but it’s not.

We’re about a quarter of the way through the book, so I have another three articles like this to get through, plus a summary.

- Until next time.