Pension Fund Reform – Tony Blair Institute

Today’s post looks at a paper from the Tony Blair Institute on the topic of pension reform in the UK.

Context

Last week we looked at the debate around the potential to use some of the money in UK pension funds as growth capital for the UK economy.

- This was triggered in part by a paper from the Tony Blair Institute, and today we’ll look at that paper in detail.

The Blair Institute (TBI) paper is called “Investing in the Future: Boosting Savings and Prosperity for the UK”.

- The key proposal is to pool public and private sector DB pensions into a number of “GB Superfunds” with up to £500 bn in assets each, similar to funds that already exist in Canada and Australia.

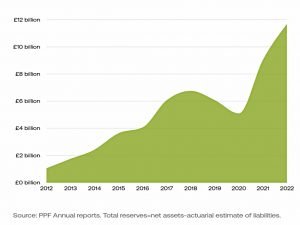

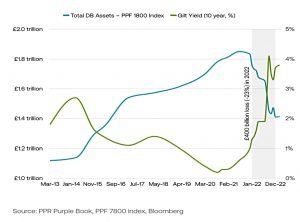

The chart shows the growth in the reserves of the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) – a £39 bn lifeboat scheme for UK pension plans – which would become a fund consolidator under the TBI proposals.

- The reserves have grown due to the investment performance of the fund.

At the moment a pension scheme needs to fail in order to be taken over by the PPF, but under the TBi plan, small schemes would be tax-incentivised to merge with the PPF.

The PPF would grow to £400 bn, be renamed “GB Savings One” and would invest 25% of its assets in UK infrastructure, listed firms and start-ups.

Today we’ll focus on the problem and it’s causes, rather than the specific proposal that we looked at last time.

The problem

Over the past 20 years, this country has seen the abandonment of investment in the domestic economy by United Kingdom pension funds, with the almost total liquidation of their holdings in listed UK equities built up over generations. This has depressed UK companies’ valuations, constrained business investment and limited the supply of growth capital to improve productivity and fund innovation.

UK pension fund returns have been poor and investment as a share of GDP has fallen.

The root cause is identified as accounting changes around the turn of the millennium.

In 1997 the government eliminated the dividend tax credit to encourage companies to reinvest profits rather than pay them out in dividends. An unintended impact of the move was to make it less attractive for UK pension funds to hold shares in listed UK companies.

The second change, in 2003 converted pension funds into contractual obligations for companies.

The Accounting Standards Board introduced requirements for UK companies to include pension-fund assets and liabilities on their balance sheets. Assets would be shown annually at prevailing market value (that is, with no allowance for future returns) and, crucially, total future pension liabilities would be discounted by, in effect, a fluctuating long-term bond rate.

At the time, this meant that many firms had very large pension deficits.

There were around 15 FTSE 100 companies whose pension-fund liabilities exceeded their market capitalisations. International Airlines (formerly British Airways) with a market capitalisation of £4 billion in 2006, had gross pension liabilities of £12 billion. IAG was subsequently described as a giant pension fund with an airline attached.

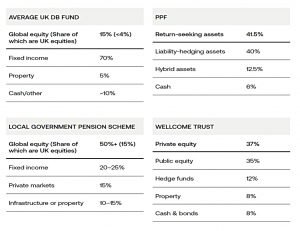

The asymmetry of being contractually responsible for pension liabilities but with no entitlement to upside performance from the assets meant that pension trustees became very risk-averse.

- They sold off their equity holdings and replaced them with bonds.

Most of the (private sector) DB schemes were also closed to new entrants, in order to cap liabilities (and prevent pension funds becoming larger than their market cap).

Of the 7,800 active pension funds in operation in 2005, just over 450 remain open to new members today, down 95 per cent.

Yet as interest rates continued to fall and life expectancies continued to rise, liabilities got bigger.

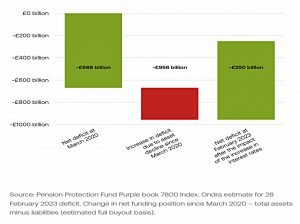

Total UK pension fund liabilities increased from £890 billion in 2010 (when the ten-year gilt was 4 per cent) to over £1.8 trillion in 2020 (when the ten-year gilt was 0.2 per cent).

Of course, falling interest rates also meant that assets (bonds) increased in value.

UK market decline

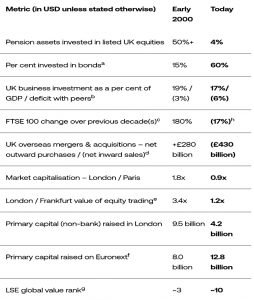

UK capital markets are in a weaker position now than they were in early 2000:

In early 2000, the London Stock Exchange (LSE) was the world’s third largest, with a market capitalisation of $2.6 trillion – roughly double that of Paris at the time – while the Financial Times Stock Exchange 100 Index (FTSE 100) had almost tripled over the preceding ten years. The LSE hosted around three times more companies than Paris and the UK’s four most valuable listed companies were among the 25 largest in the world.

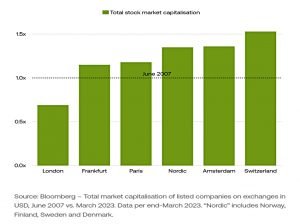

The UK is the only major market whose value is below that of the 2008 financial crisis.

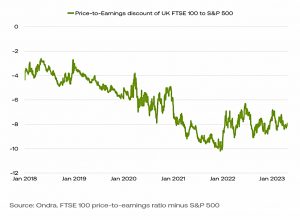

The UK market PE has fallen relative to that of the US.

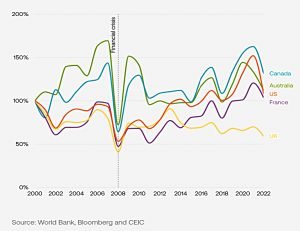

And relative to GDP.

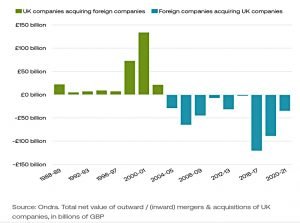

The UK has also flipped from being a net acquirer of foreign companies to having net inward

acquisitions following the pension changes.

DB Pension Funds

The systemic fragility of UK defined-benefit (DB) pension funds was almost 25 years in the making, stemming from tax and regulatory changes in the late 1990s, falling interest rates and the adoption of liability-driven investment (LDI) strategies.

Since 2004 UK companies have been obligated by TPR [The Pensions Regulator] to make additional deficit reduction and higher contribution payments to their pension funds totallingover £300 billion.

At least some part of this total could and should instead have been deployed to fund growth and scale, to invest in productivity-enhancing technology, to expand globally, to invent and commercialise new drugs or to improve competitiveness through innovation.

There was no realistic way for a company to recover these contributions if, for example, the direction of interest rates reversed (as in fact has happened over the past two years).

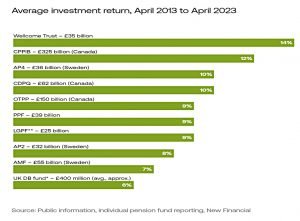

In the decade before the [accounting] changes were introduced, the UK’s DB pension funds returned an average of approximately 9 per cent to 10 per cent per annum18 while, in the two decades since, they have averaged just 6 per cent.

The report notes that larger funds show better returns.

That’s it for today.

- The TBI paper includes some interesting background data on the accounting changes, the pension fund response and the consequences for the UK stock market.

The superfund proposal is a good one, but:

- Investors won’t vote for a higher level of UK stock investments until there is a positive track record.

- Compulsion might be used to promote superfund investment in UK projects and firms (for say 20% to 25% of the fund) but at what political cost?

- The fiduciary duty of pension trustees is to invest in what they think makes the continued payment of pension most likely, and this will have to be modified if the scheme goes ahead.

- There are also career incentives which mean that most pension professionals will object.

- Extending the proposals to DC funds can’t be compulsory (since individuals manage their own pots) and there are likely to be few takers on a voluntary basis.

Until next time.