Renaissance – Too Good to be True?

Today’s post looks at a paper from Bradford Cornell about the Medallion Fund from Renaissance Technologies.

The Ultimate Counterexample

Bradford Cornell is Professor Emeritus at UCLA Management School.

- His paper was published in 2019 and is called “Medallion Fund: The Ultimate Counterexample”?

The Medallion Fund is the flagship vehicle of Renaissance Technologies (RenTec).

- RenTec was built by Jim Simons, a process described in Gregory Zuckerman’s recent book “The Man Who Solved The Market”.

We’ll be looking at the book in detail at some point in the future, but (spoiler alert) be warned that it doesn’t give too much away about the systems RenTec uses.

- Even more disappointingly, Simons closed the Medallion fund to outside investors in 1993 (( Or 2003, depending on which source you accept )) and returned their cash.

The Medallion Fund is now run just for RenTec employees.

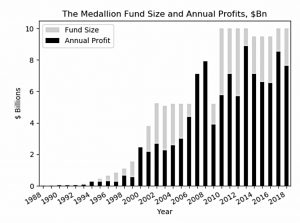

- And there appear to be large distributions each year to keep the fund at a constant size.

Medallion returns

The counterexample to which Cornell refers is against the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH).

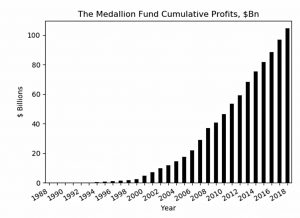

From the start of trading in 1988 to 2018, $100 invested in Medallion would have grown to $398.7 million, representing a compound return of 63.3%.

During the entire 31-year period, Medallion never had a negative return despite the dot.com crash and the financial crisis.

The fund’s market beta and factor loadings were all negative, so that Medallion’s performance cannot be interpreted as a premium for risk bearing.

Market returns from 1988 to 2018 were 10.0% pa. compared to 63.3% gross for Medallion (39.2% after very high fees).

In 31 years, Medallion would have turned a $100 investment into a $400 million fortune.

There have been no losing years on a gross basis, and the last after-fee loss was 1989 (-3.2%).

The arithmetic mean of annual returns was 66.1% with a standard deviation of 31.7% (quite racy) for a Sharpe Ratio of more than 2.

- Nor did returns tail off as the fund grew in size from $20M to $10 bn.

Clearly, under the EMH, this is not supposed to happen.

There is no adequate rational market explanation for this performance.

Perfect foresight

Cornell’s first test is “perfect foresight”

The perfect foresight returns are the returns that would be earned by investing in the market whenever the subsequent return exceeded that on Treasury bills and buying Treasury bills when it did not.

Annual foresight turns the $1,815 returns (from a base of $100) of the market into $7,539.

- Monthly foresight turns this into an impressive $331K.

Which is still 1000 times less than the Medallion returns of $399M.

Strategy

Zuckerman’s book gives little away – Medallion opens and closes thousands of short-term positions, both long and short.

The win rate is surprisingly modest. RenTec’s Bob Mercer said:

We’re right 50.75% of the time . . . but we’re 100% right 50.75% of the time. You can make billions that way.

Note however that many traders (for example trend followers) would expect a win ratio of around 40%, so 51% is not bad at all.

Medallion was also not correlated to the market:

A regression of Medallion’s excess returns on the CRSP market index produces a beta of approximately -1.0 so that in addition to its extraordinary performance Medallion also offered a hedge against market risk.

A three-factor regression adding the Fama and French (1996) variables SMB and HML reveals that loadings on both factors are also negative, though neither is statistically significant.

Although returns held up well as the fund grew to $20 bn, there are three reasons to believe that there is a scale limit to the Medallion strategies:

- the fund has been closed to outsiders,

- annual distributions are used each year to keep the fund at a constant size, and

- the returns on the other RenTec funds which are open to advisors are more in line with the industry.

Conclusions

Cornell offers no explanation for Medallion’s outperformance, merely noting that it is worthy of further consideration as a challenge to the EMH. He said:

It was like the sun rising in the west. I’ve been a finance professor all my career, I’ve read thousands of papers on investment performance, and I’ve never seen anything like it.

The other two funds are doing well, but it’s nothing out of the ordinary. They’re like going out into my backyard and seeing a coyote and a raccoon. [Medallion?] It’s like I saw a T. rex in my backyard. I just don’t get it.

Zukerman commented:

Medallion’s returns are less perplexing to me, though no less remarkable. An overlooked key is ample and cheap leverage. You get that by having consistent returns and a crazy-high Sharpe ratio.

That, in turn, comes from the firm’s numerous advantages and advances — superior talent, better data, a unique management approach, a focus on midfrequency trading, a willingness to cap the fund, and more.

Simons himself has said:

Work with the smartest people you can … be persistent … be guided by beauty.

I guess we might never know exactly how the fund was so successful.

- Until next time.

References

- Medallion Fund: The Ultimate Counterexample – Bradford Cornell, SSRN

- Famed Medallion Fund “Stretches Explanation to the Limit,” Professor Claims – Amy Whyte, Institutional Investor

- The Man Who Solved The Market – Ifor Williams, Medium

- Renaissance Technologies Medallion Fund: An Exception to the Indexing Rule – Ben Felix, PWLcapital.com