The End of Inflation

Today’s post looks at the end of inflation.

Contents

The End of Inflation

This post is the first in a series of three:

- Today, we’ll look at whether and why inflation has gone away

- In the second article, we’ll look at helicopter money

- In the final article, we’ll examine modern monetary theory (MMT)

For most of my life, I’ve been afraid of inflation.

- It erodes the value of money, and before you learn how to build a diversified portfolio, this is a frightening prospect.

Of course, even a diversified portfolio won’t protect you against Venezuela- or Zimbabwe-style hyperinflation, though a healthy allocation to overseas assets will help.

Later on, you get a job, and your pay rises are often linked to inflation.

- Then you borrow money to buy a house, and for a short period, inflation is your friend.

It shrinks your debt in real terms and makes it more affordable to repay.

Then you pay off your mortgage and retire, and you need inflation for a different reason.

- It’s hard to make decent returns from your pension pot when inflation and interest rates are low.

Nevertheless, that’s where we are now.

- A decade of QE (central banks buying bonds) since the 2008 financial crisis has pushed up asset prices, but not inflation.

Neither has a booming jobs market.

How it should work

Governments set tax rates and the amount of public spending (the size of the state) in order to stimulate the economy.

- A booming jobs market usually means votes for the incumbent.

But if the economy overheats, this will produce inflation, which might lose votes.

- So the central bank takes away the punch bowl by raising interest rates when it fears this might happen.

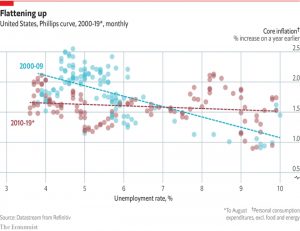

The traditional relationship between unemployment and inflation is known as the Philips curve.

- Note that the curve can fail at either end – if unemployment gets too high, inflation should fall.

This failed to happen after the 2008 crisis.

What’s changed?

Low unemployment no longer seems to mean higher wages and therefore higher inflation.

- In turn, this means that interest rates have remained low and there is little scope for cuts to stimulate the economy when the next recession hits.

So tax cuts and public spending (deficit spending) are likely instead.

- Luckily, low interest rates mean that funding national debts is cheaper than ever.

Ideally, this spending will be used to fund infrastructure (travel, tech and renewable energy) that will boost productivity and hence growth.

Interest rates are also low because of a glut of savings, a reluctance by companies to invest, and of course because QE pushes up bond prices and therefore pushes down yields.

- Indeed, 25% of investment-grade bonds ($15 trn) now trade at negative yields.

The average developed country central bank now has a balance sheet worth 35% of GDP.

Why has this happened?

It seems that the public has come to expect low prices.

- It’s also the case that global supply chains don’t need to take account of labour market conditions in the local consumer’s market.

The internet is also to blame, and in particular, Amazon:

Amazon’s prices are 6% lower than those of eight large retailers, and 5% lower than on those retailers’ websites.

This, in turn, is linked to the globalisation of supply chains.

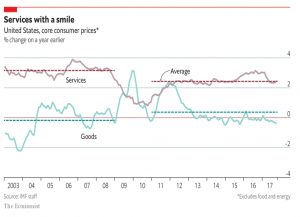

It’s less easy to explain why services inflation is lower, though free services delivered over the internet might have something to do with it.

- Of course, many “free” services are funded by advertising, which has been around for a long while and is not a large part of the economy.

To measure the value of something free, researchers offer to pay someone to give it up.

- The median response for Facebook was $42 per month (( I would take any amount )) and for Google Maps, $64 per month.

Online search came in at $1,460 per month.

Technology

More broadly, technology allows an economy to produce more with limited resources, so it is a disinflationary force in itself.

- If demand does not keep up with the increased supply, prices should fall.

It’s also a possibility that some tech advances are not captured in official statistics.

Because it takes a while for statisticians to notice that consumers are buying new products, they miss precipitous price falls early in a product’s life. It is also hard to tell how much better new products are than what went before.

The ability of smartphones to replace multiple devices and services is a case in point.

- The implication is that true inflation is even lower than the public figures.

And that targeting inflation as a meaningful representation of the experiences of consumers is flawed.

Globalisation

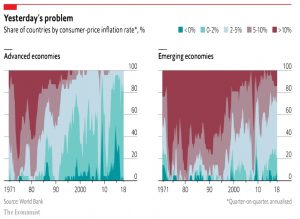

International trade grew from 39% of world GDP in 1990 top 51% by 2000.

- Over the same period, inflation both fell and became more synchronised across borders.

So if globalisation reduced inflation, could things like the US-China trade war and Brexit bring it back?

- Perhaps, in the UK (because of the fall in Sterling).

But in the US, the trade war has sparked fears of a global slowdown and a rush to safe Treasuries, pushing yields down and the dollar up.

- This deflationary impact is greater than the inflationary impact of Trump’s tariffs.

There are three global influences on inflation:

- commodity prices

- trade in goods, and

- capital flows

Commodity prices have been driven in recent years by demand in emerging markets, particularly China.

The (lower) price of goods has similarly been driven by shifting their production to emerging economies with low labour costs.

- The average country imports 20% of the change in inflation in the rest of the world.

- At the same time, prices in local services remain sensitive to the domestic economy.

On the third point, one cause of globally -synchronised falling real interest rates is a global savings glut.

- Causes include ageing populations, low productivity growth, low supply of safe investment assets and a lack of private sector investment opportunities.

QE hasn’t helped, either.

Why does it matter?

The Economist gives three reasons why we should care about inflation below target:

First, it represents a missed opportunity. Monetary policy could have been looser, and hence growth faster, without price pressures taking off. Second, central banks missing their inflation targets undermines their credibility.

Most important, low inflation can be self-reinforcing. More significant than the nominal

interest rate set by central banks is the real interest rate. As the public comes to expect lower inflation, the real rate rises, weakening demand and pushing inflation down even more.

What to do about it?

The Economist has three goals for policy reform:

- an improvement to how banks fight recessions

- a way to overcome a flat Phillips curve, and

- stimulus-of-last-resort via fiscal policy.

The first requires a different inflation target – perhaps an average of 2% over an economic cycle (rather than a 2% cap), or an explicit long-run prices target.

For the second, central banks could target nominal GDP rather than look directly at unemployment levels.

The third is more difficult – automatic changes to say payroll taxes as unemployment rises would help.

- An additional fiscal weapon would be “a handout to the public in which every adult received an equal share of newly created money”

Otherwise known as helicopter money.

That’s it for today’s scene-setting.

- In the next article, we’ll look at helicopter money in more detail.

Until next time.

Sources

- The world economy’s strange new rules – Economist (and associated articles from the same issue).

Interesting article and I look forward to reading the next two instalments.

However, whilst it is true that annual UK inflation is currently at relatively low levels (around 2.1% average for the last decade using HMG’s preferred CPIH measure vs about 4% average (using RPI) over all ten year periods since 1915) is it not a bit tongue in cheek to describe this as the “end of inflation”? After all, might not our current national pursuit of “back to the 70’s” also bring a resurgence of 70’s levels of inflation too?

It’s not tongue-in-cheek exactly – my point is that what’s already taken place should have generated inflation, and I can’t see any inflation further down the track. Plus we haven’t been able to normalise interest rates and so the regular tools for tackling recessions aren’t available to us.

So I want to look at what might happen instead (helicopter money / MMT) and whether they might lead to inflation.

OK, but it is worth noting that >20% of all the ten years spans from 1915 have an average RPI of 2.5% or less. Interestingly, most of these periods were during the 1920’s & 1930’s. Whilst I am no economics historian and what we are currently seeing certainly seems unusual (to my living memory, at least) it is not unprecedented. I have separately emailed you a supporting graphic.

Do you know if QE is unprecedented? If it is, then I suspect this may go a long way to explaining the current unusual inflation figures.

It’s not that there are no precedents, they are just ugly ones. I don’t want to think that we are living through a re-run of the 1930s, with WW3 to come as an exit strategy. My main question is what will fix this, and how do we do it without triggering hyperinflation/currency collapse?

As for QE, my understanding is the US tried it in the 1930s (too little, too late) and Japan had something similar from 2001. So not unprecedented but unusual.

Re precedents, agree totally re re-run of 20’s/30’s with WW3. UK also experienced ten year long low average level of inflation (RPI 2.5% or less) for a few years from early/mid 1990’s too – so thankfully WW3 is not the only possible outcome foretold by historical precedent.

Re QE, that is now my understanding too.

And, was it not also the case that in the previous US QE experiment, their economy only returned to “normalcy” (regular economic tools working/behaving as anticipated) after that QE was unwound?

2000 to 2009 includes two major crashes/recessions, and we haven’t recovered from that one yet. In the 30s, the US didn’t get back to normalcy until they won WW2 (and everybody else lost). I’m glad you can see happy endings, but I can’t at present.

I guess time will tell.

I’m not sure I see entirely happy endings (e.g. BoJo or Corbyn, crikey how did we get here?) but I just do not see that crisis outcome(s) are inevitable.

For example: a) the levels of UK RPI inflation in the 20’s & 30’s were far lower (and often negative) than now, whilst Germany suffered hyper-inflation b) agree market has not really recovered from the 2000 crash, but that just may mean that there is still room for the market to grow

My own belief (for that is all it can be) is that a lot of people are prematurely calling time on inflation and much of this is down to recency bias. I can remember the 70’s and the shenanigans of the aforementioned politicians really do in many ways feel like “back to the 70’s” for me. And I would not call that a happy ending!

In any case, I look forward to your next two articles.

As always a very good report of something that is talked about a lot.

Inflation is a bit of a bogey man – my elderly relatives still talk about living with 10% inflation and 10% plus interest rates but don’t think for a second that since everyone was experiencing the same pressures, the “modest” house that they paid £20k for back in the day is now worth half a million quid.

Yet they moan about the fact that they can’t buy milk for less than a pound for 2 litres.

You’ve maybe covered it before but there is a great disparity between deflation/inflation you can avoid and what you can’t. A good example is music – LPs, cassettes and CDs used to cost a fortune – now they are practically free or cost no more than £100 a year.

Massive savings

On the other hand, (take your pick but it’s something you can’t avoid) – our nursery is putting up prices in excess of inflation this year. Not massively but it makes our nursery bill twice that of our mortgage (or 7 times that of the interest on the mortgage).

Debt cheap, assets expensive, people prohibitive (be it small ones or minimum wage ones).

Some of that helicopter money would be nice but if you don’t get tax credits from the government, child benefit has been frozen since 2010.