The Equity Edge 3 – Valuation and Qualitative Analysis

Today’s post is our third visit to a new book – The Equity Edge by Mark Jeavons.

Contents

Book Valuation

Chapter 9 looks at valuation ratios based on book value rather than earnings, sales or dividends.

Book value

Tangible book value (or net asset value, NAV) is the total of the company’s assets minus its liabilities.

- Intangible assets (goodwill, brands, IP etc.) are excluded, even though they are increasingly important.

The significance of book value is arguably diminished in the internet age.

- The question is to what extent a large quantity of assets is required in order to generate revenues in the digital world.

This is not a one-way street:

- goodwill is a non-productive intangible, but

- IP and brands can be very productive.

So what is needed is a valuation somewhere between book value and tangible book value, which strips out only the unproductive intangibles.

- This is sometimes known as the fundamental value.

Book value is the foundation of value investing, which is currently suffering it’s greatest period of underperformance ever.

- As well as the increasing significance of intangibles, it’s also the case that accounting rules have changed since the heyday of value (the 1970s and earlier).

Mark partially acknowledges the issue:

Book value measure is most suitable for companies that have a great number of high-value assets or an asset-intensive business, such as utilities and telephone companies, where a large amount of infrastructure is required.

Other asset rich-firms include property companies and financials (banks and insurance firms).

- That said, Mark likes to see a rising NAV ps.

Price to Book

Price to book (PTBV) divides the share price by the NAV ps.

The lower the PTBV ratio, the more likely the company is good value.

But as they say, sometimes things are cheap for a reason.

Mark looks for a PTBV below 2, though below 1 would be even better.

Companies with a PTBV above 10 are likely to be expensive and should be avoided.

As an inverse of book value, PTBV will be inflated for capital-light firms which rely on IP, or indeed many service companies.

- Mark also cautions against firms with recent large acquisitions and this can increase book value (through the full price paid for new assets) and reduce PTBV.

So PTBV is best seen as a comparative measure within industries.

- Mark recommends that we exclude firms with a PTBV higher than 1.5 times the sector average.

Mark also notes that firms with high ROE are likely to be expensive in the market and to, therefore, have a high PTBV.

- I think that ROE is the more useful measure of the two since I am an equity holder, not an asset scavenger.

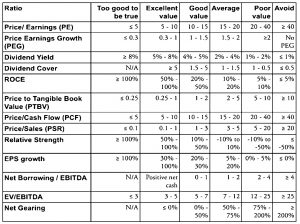

Combining valuation ratios

We’ve reached the end of the chapters on valuation ratios, and Mark provides a summary table of the values that he’s looking for.

Qualitative analysis

Mark’s take on qualitative analysis is a version of the SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) analysis I learned at business school 30 years ago.

His information sources include annual reports, company websites and the Investor’s Chronicle – which I have to say I see as an upmarket tip sheet.

- That’s not to say that subscribing for a year or two wouldn’t give a new investor a good introduction to the UK market.

The Directors’ Dealings section is useful, though you can source this information elsewhere.

He also recommends the FT (very poor for investors in recent years, though still reasonable for news and Bloomberg (newsy and often pay-walled, though I must recommend John Authers’ newsletter – he moved across from the FT in 2019, I think).

These days I get most news from the internet.

- Twitter is especially useful for providing a diverse set of starting points for your own research.

I also follow a lot of blogs, mostly American.

- If you read my weekly reports and check out my subreddit you be able to figure out which are my current favourites.

Mark mentions ADVFN and Motley Fool.

- I would avoid both of these as they tend to attract the least sophisticated and/or scrupulous investors in the land.

Business model

The business model just means the way a company makes money.

- I would agree that understanding where the cash comes from is a pre-requisite to investing in a firm.

You’ll want to look at subdivisions and business lines separately and works out which ones have the biggest impact on the bottom line.

- You should also work out the future impact of any discontinued operations.

Companies are required to provide a breakdown by “segment”:

Reportable segments are determined by geographical area; business class; 10% or more contribution to revenue; profit or assets; sector differences in terms of return, risk, growth or development potential for investors.

For each segment, firms must provide sales, profit, costs and net assets.

- This will allow an investor to identify growing and shrinking segments.

Ideally a company should be focused on its main area of interest, focusing on businesses that naturally complement each other.

This has not always been a popular view.

- Conglomerates were all the rage in the 60s, 70s and 80s.

- Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway is probably the nearest thing we have to one today.

You should also consider the suppliers to a company and its customers.

- In particular, avoid firms with a concentration in these areas.

You also need to identify the growth strategy of the company.

- Will it be organic (low-risk) or by acquisition (high-risk).

Be wary of diversification into fields outside the firm’s core competence.

- Instead, look for synergies and “bolt-on” acquisitions.

Competitive advantage

We’ve seen previously that the best evidence of competitive advantage (or an economic moat) is a high ROCE, a high profit-margin and a lot of free cash flow.

- Mark feels it is also worthwhile to articulate a company’s sources of competitive advantage and try to work out whether they will continue in the future.

There are a few options:

- low cost of production, and hence low pricing

- product differentiation (lack of substitutability)

- dominating a niche

- brands and IP, tolls (eg. Visa)

- brand extensions (eg. Apple moving from phones to watches, and from hardware to software and media services)

- increasingly, network effects and switching costs

Management

Mark sees management as a key factor in every successful company, whereas I’m with Buffett:

I try to invest in businesses that are so wonderful that an idiot can run them. Because sooner or later, one will.

I make a slight exception for founder-run businesses and an even slighter-one for family run-businesses.

- But to me, hired-hand management is like politics – it’s a branch of show-business open to ugly people.

Here are a few tips from Mark:

You want to see executives that have either been with the company a long time or have a transferable background to the company they are working for.

When a founder or chief executive has been the driving force behind a company for many years you need to consider what succession plans are in place.

[Conference] calls provide insight into management style. You should look for management providing candid, forthright answers that are easy to understand.

It is worth checking whether the remuneration for management is excessive or not.

Your preference should be to invest in companies where the main board owns less than 50% of the issued share capital and where there is large institutional investment.

If key members of the management team have all been selling large amounts of shares you should be wary of investing.

Broker valuations

Chapter 11 walks us through the process of deriving a consensus view of how brokers view the prospects for a company, without quite disclosing whether Mark feels that such a view has any value for the private investor.

In my opinion, it does not.

- Brokers have obvious conflicts of interest (they want the company’s business and they want to avoid jeopardising their own career).

Studies have shown that most forecasts are merely (somewhat optimistic) projections of the past, and have no predictive value.

- It is telling that brokers and analysts make so many more buy recommendations than sell recommendations.

There are two ways in which broker forecasts can be useful:

- with small companies (say, AIM in the UK), the broker figures are likely to be the company’s own internal figures

- trends in broker forecasts can be useful – we want the predictions to be improving, even if they are wrong.

Conclusions

That’s it for today – we’ve covered another three chapters, and it’s taken fewer words than in the previous articles in this series.

- There are five chapters to go, which means there will be another two articles before the summary.

After that, I’ll try to distil Mark’s advice into a few Stockopedia screens.

- Until next time.