Weekly Roundup, 18th October 2021

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at the 60/40 portfolio.

60/40 blues

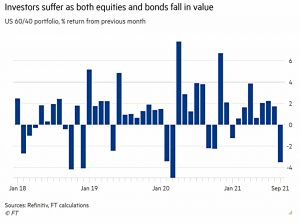

In the FT, Eric Platt and Michael Mackenzie reported on the recent hit taken by the traditional 60/40 portfolio.

- The 60/40 lost 3.5% in September, the biggest fall since March 2020, and the first loss since January 2021.

Inflation fears hit stocks and the fear of interest rate rises in 2022 pushed up bond yields.

Over the past four decades (during which inflation and interest rates have steadily declined), 60/40 has provided good returns and lower volatility than stocks.

During the decade from 2010, the 60/40 portfolio provided an annualised return of 10.2 per cent and provided investors with a gain of 15.3 per cent last year.

But this depends on stocks and bonds not falling in tandem, and the historic performance is unlikely to be repeated now that both stocks and bonds are highly-priced.

Seth Bernstein, CEO of AllianceBernstein said:

The 10-year yield can easily rise to 2 per cent. Investors are entering a period of much greater volatility for bonds given the uncertainty over inflation and the small amount of income they now provide.

We’ve been running a series of articles on how to diversify away from the bond element of 60/40.

- Stay tuned for part five of “Rethinking 60-40” in a few weeks.

Stagflation

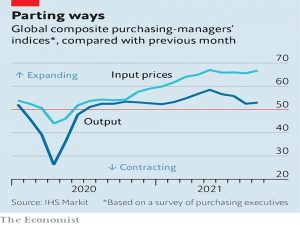

The Economist decided that we probably aren’t heading back to the stagflation of the 1970s.

- Stagflation is a combination of two things – high inflation and low growth – that do not normally go together.

- In the 1970s, it was triggered by OPEC’s oil price shock.

So far in 2021, we have had decent growth and falling unemployment, but the post-pandemic recovery looks to be running out of steam.

- And inflation has his 3% in the UK and Europe, and 5% in the US (still much lower than the 1970s).

We also have energy- and food-price shocks, high shipping rates and higher wages.

- Ans we must consider the attitude of central banks towards tolerating inflation – now, as in the 1970s, low unemployment is seen as more important.

The “good” news is that weak unions and the end of COLA (cost of living agreements) mean that wage rises may not be sustained.

- And productivity – one of the problem areas in the 1970s – has increased recently.

I guess we’ll just have to wait and see.

Home bias

In FT Adviser, Damian Fantato reported that Vanguard is dialling down the UK home bias in its LifeStrategy funds.

At the moment the Vanguard Lifestrategy 100% Equity fund has a 22 per cent exposure to the UK, while the Investment Association Global sector has a 7.3 per cent exposure to the UK.

The UK market’s share of the global equity market cap is now down to around 3.6%.

- We’ll get into the technical arguments in a moment, but it’s worth noting that Vanguard’s reasoning is based around “the changing commercial case” (ie. what sells).

Peter Westaway, Vanguard’s European head of investment strategy, said:

Since Lifestrategy was launched there used to be a much larger home bias. There is a process where we review features of the funds such as its home bias and we have been gradually dialling it down.

There is still a demand out there for people in the UK to have a slight home bias but that tendency is shrinking all the time. Increasingly there are people asking the question. That’s the direction of travel and it is a matter of opportunistically dialling it down.

That analysis is surely correct, but why?

- I would argue the dominance of US Tech stocks over the last dozen years (plus to a lesser extent the revulsion of Remainers towards anything British) is responsible.

This makes today a questionable time to reallocate away from the UK, particularly towards a global market cap model which will be 60% allocated to the US (which in turn is dominated by the tech stocks).

- I refer to this as “away bias”, though really it’s just an overallocation to the US.

Market cap is a dumb way to index, but it makes life easy for the indexers.

- I think there are reasons to have a higher allocation to your home country (information, trading fees, lack of FX exposure, eligibility for all account types etc.) but of course, you need to keep an eye on your allocation.

I’m at 13.8% UK stocks just now, but 8.3% of that is down to a couple of active strategies which are easier to access/implement in the UK.

- My passive exposure is 6.5% which is fine by me.

Commodities

In The Economist, Buttonwood tried to make sense of the chaos in the commodity markets.

The Dow Jones Commodity Index rose by about 70% in the year to June. But the rally has since run out of puff. Some materials, such as lithium, continue to climb.

Other once-hot commodities have gone into reverse. The price of iron ore is down by 45% since its peak in mid-July; lumber, by 63% since early May.

The last supercycle in commodities ended in the mid-2010s when Chinese growth ebbed.

- This time the drivers of the market are a series of supply and demand shocks, rather than sustained growth.

There is a sustained drive from governments to greenify their economies.

- This needs wood, industrial metals to build wind and solar farms, lithium, and natural gas.

And there are geopolitical tensions, particularly around energy.

All this plays out in storage ways, for example in response to the high oil price:

Shale wells in America, often quick to turn on the taps, are instead paying down debt.

That would typically boost corn, the main component of American biofuel. But President Joe Biden is mulling a cut to the amount of biofuels refiners must blend into the total fuel pool, dampening demand.

The price of palladium, used to make catalytic converters, has slumped by 25% in the past month because a shortage of microchips has halted car production.

Some observers predict that things won’t settle down until 2025.

Beyond Petroleum

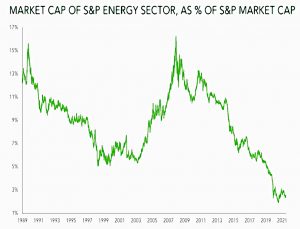

Ruffer’s Investment Director Duncan MacInnes explained why his firm is still investing in big oil.

The energy sector has fallen from 16% of the S&P 500 just 13 years ago, to below 3% as of today. If you looked back to the early 1980s you would have seen it was more than 20%.

Despite this, oil majors make up more than 6% of Riffer portfolios. There are three reasons:

- the energy sector will respond to economic growth

- it’s an inflation hedge

- and the industry itself is evolving

Pressures on capital expenditure into exploration and production mean that supply is tightening.

- But demand is still increasing and is expected to do so for at least another five years, as emerging markets become wealthier and want more cars, A/C and international travel.

This should mean higher prices, but for many asset managers who want to project a green agenda, energy stocks are uninvestable.

Duncan runs through the numbers for BP:

BP is an $92bn company with an additional $38bn of debt. At $75 per barrel of oil, BP produces at least $15bn in free cash flow, which is being returned to shareholders via a 5% dividend yield, a further 6% buyback plus paying down debt. A 16% return is interesting.

And this is after spending $4 to $5 bn per year on renewables.

- In five years, BP will also be one of the world’s biggest renewables companies, at which point the firm might become investable once more, and perhaps worth more than its current value.

The market values BP and peers like they won’t exist in the not-too-distant future. By 2025, we should have proof they will be with us long Beyond Petroleum.

Monzo

Monzo has pulled its application for a US banking licence, after being told that it was unlikely to be approved.

- According to the FT, the US is more cautious than the UK about letting loss-making startups become banks.

It might still be possible for Monzo to compete in the US, as competitors like Chime (now valued at $25 bn) have grown without one.

Higher card interchange fees in the US make it more sustainable for companies to share revenue with fully licensed partner banks, unlike in the UK.

Monzo follows Robinhood and Square in withdrawing its bank application; Revolut’s remains outstanding.

Despite the fabulous success amongst millennials of its semi-viral marketing campaign, I’ve never seen the point of Monzo – it doesn’t come out on top in any category that’s important to me.

- I have accounts with Starling, Wise, Revolut, Marcus and Chase, as well as with four phone trading apps, so this is not an early adoption issue.

Quick Links

I have four for you this week, the first three from The Economist:

- The Economist looked at the first big energy shock of the green era

- And asked whether the world economy is entering a wage-price spiral.

- The newspaper also examined how Adobe became Silicon Valley’s quiet reinventor.

- Alpha Architect asked whether a big value spread would mean big returns to value strategies.

Until next time.