The Honest Truth 1 – SMORC, Fudge and Golf

Today’s post is our first visit to Dan Ariely’s third book – The Honest Truth About Dishonesty.

Contents

Enron

Dan begins his third book with Enron.

Through a series of creative accounting tricks–helped along by the blind eye of consultants, rating agencies, the company’s board, and the now-defunct accounting firm Arthur Andersen, Enron rose to great financial heights only to come crashing down when its actions could no longer be concealed.

Dan met a guy who had consulted for Enron.

He hadn’t seen anything sinister going on. He had fully bought into the worldview that Enron was an innovative leader of the new economy. Once the information was out, he could not believe that he failed to see the signs all along.

Dan became interested in the idea that dishonesty is linked to “wishful blindness”.

I wondered whether my friends and I would have behaved similarly if we had been the ones consulting for Enron.

Dan wanted to know where dishonestly comes from, and whether it is restricted to a few bad apples.

- The answer to the second question would inform how we should try to deal with the problem.

SMORC world

The received theory on dishonesty came from Nobel Prize-winner Gary Becker, who says that people commit crimes based on a rational analysis of each situation.

- He came up with the theory when running late for a meeting.

Having weighed up the costs and benefits of the options, he decided to park illegally.

- This is known as the Simple Model of Rational Crime (SMORC).

The essence of Becker’s theory is that decisions about honesty, like most other decisions, are based on a cost-benefit analysis.

SMORC would imply more surveillance (by CCTV and officers) and more punishment (stiffer fines and sentences).

But as we know from Dan’s other books, he doesn’t think that people are rational.

- He mocks “SMORCworld”:

We would be unwilling to ask our neighbors to bring in our mail while we’re on vacation, fearing that they would steal our belongings. We would watch our coworkers like hawks. Legal contracts would be necessary for any transaction. We might decide not to have kids because when they grew up, they, too, would try to steal everything we have.

On the other hand, I’m pretty rational, and I think that small decisions (illegal parking, not murder) could involve a quick cost-benefit calculation.

Dan thinks that in SMORCworld we would all cheat and steal a lot more than we do.

- But perhaps we don’t get the opportunity, or we decide that the long-term pain outweighs the short-term gain.

Art thieves

Dan tells the story of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC.

- The gift shops – staffed by art-loving retiree volunteers – sold $400K in merchandise each year, but lost $150K in “shrinkage”.

When the honesty system (cash boxes from which the vols made the change) was replaced with an inventory system and sales records, the thieving stopped.

The multitude of elderly, well-meaning, art-loving volunteers would help themselves to the goods and loose cash lying around.

It looks like people will steal when they get the chance.

Interestingly Dan takes this story as evidence against the idea that cheating is down to one man doing a cost-benefit analysis.

- The guy who took the cash to the bank was initially suspected, but he was only stealing a little bit.

So Dan and I are closer than I thought:

- We both think that many people will cheat when they get the chance.

But Dan thinks there is no cost-benefit analysis, whereas I think that depends on the personality of the guy doing the stealing.

Testing SMORC

Chapter 1 begins with Dan’s story of a fake motivational speaker/role model that he invited to one of his classes.

- This guy (stand-up comedian Jeff Kreisler, the author of “Get Rich Cheating”) encouraged people to cheat in order to get rich.

The downside is you might get caught, but Dan notes that getting caught is not the same as getting punished.

- Dan has something of a fixation with what he sees as the lenient treatment of white-collar crime.

The three elements of SMORC are:

- the benefit from the crime

- the chance of getting caught

- the punishment if you do get caught.

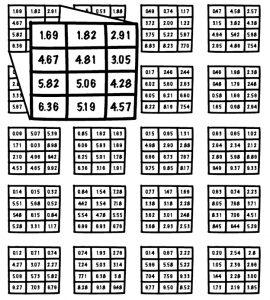

To test this, Dan and his colleagues designed an experiment around matrices.

- Subjects had to spot the two cells which added up exactly to 10.

They had five minutes to solve as many as possible and would be paid fifty cents per correct answer.

Controls handed their sheets to the experimenter, who checked the answers, smiled and paid the subject.

- The shredder subjects shred their answer sheet and merely report their answers to the experiment (this obviously allows cheating).

Given the opportunity, many people did fudge their score.

Correct answers increased from 4 (out of 20) for the controls to six for the shredders.

This overall increase did not result from a few individuals who claimed to solve a lot more matrices, but from lots of people who cheated by just a little bit.

Version 2 of the experiment varied the incentives.

- Participants were promised 25c, 50c, $1, $2, $5 or $10 per matrix.

Another set of subjects guessed before the experiment that cheating would increase in line with the rewards.

- But in fact, people just added 2 to their scores, regardless of how much they were paid (in fact, those paid $10 cheater a little less).

This suggests that dishonesty is most likely not an outcome of a cost-benefit analysis.

And when the stakes are very high, people don’t feel so good about cheating.

- It’s like taking a box of pens from the office, rather than a single pen.

Version 3 of the experiment compared shredders to half-shredders (some evidence remained in the room after they left) and self payers who could shred and then pay themselves whatever they like from a bowl of money containing more than $100 in small bills and coins.

- Observers once again predicted more cheating with higher incentives.

Lots of people cheated, but just by a bit, and the level of cheating was the same across all three conditions.

In version four, a supervisor was added to the room.

- Sometimes this was a sighted person, and sometimes the supervisor was blind.

They cheated just as much when [sighted] Tali supervised the experiments as they did when [blind] Eynav was in charge. The probability of getting caught doesn’t have a substantial influence on the amount of cheating.

This is pretty amazing to me – the chances of being caught would be my number one consideration.

Version five of the experiment set different expectations for subjects, to see if they were limiting their cheating to avoid standing out.

- Half the subjects were told about the correct average score of four, and the other half were told that the average was eight.

They were not influenced even to a small degree by this knowledge. They cheated by about two extra answers. We cheat up to the level that allows us to retain our self-image as reasonably honest individuals.

Again, this is a surprise to me.

Real people

The next stage was to use non-students and to try to mimic real-life more closely, by incorporating the possibility of altruistic and charitable acts alongside cheating.

Dan sent Eynav and Tali into a farmer’s market to buy 2kg of tomatoes from several vendors.

- The quality of the tomatoes was justed by another seller who did not otherwise participate.

A traditional economist might argue that in an effort to maximize the social welfare of everyone involved (the seller, Eynav, and the other consumers), the seller should have sold [Eynav] the worst-looking tomatoes, keeping the pretty ones for people who could also enjoy that aspect of the tomatoes.

I agree, but of course, they didn’t do that – they gave nicer-looking tomatoes to the blind woman.

The next experiment was to test for cheating in cabbies, by not taking non-local passengers (tourists) to their destination via the most direct route.

- Dan carried out this experiment in Israel, where the flat fare ($5.50) on the chosen route is lower than the meter fare ($7).

Eynav and Tali always asked to have the meter activated.

Even if the drivers explained that the flat fare was cheaper, they insisted on the meter.

- Again, Eynav paid less than Tali, but this was not because they cheated Tali, at least according to Eynav.

I heard the cab drivers activate the meter when I asked them to,” she told us, “but later, before we reached our final destination, I heard many of them turn the meter off so that the fare would come out close to twenty NIS.”

They never turned off the meter for Tali, who paid around 25 NIS.

Fudge

Dan concludes that there are two warring desires inside us:

- A desire to see ourselves as an honest, honourable person

- A desire to have as much money as possible, even if that comes from cheating.

As long as we cheat by only a little bit, we can benefit from cheating and still view ourselves as marvellous human beings.

Dan calls this the fudge factor theory – we all exaggerate around the edges.

As Oscar Wilde once wrote, “Morality, like art, means drawing a line somewhere.” The question is: where is the line?

Money

Dan describes an experiment we have met before, where he hid dollar bills and Coke cans in dorm fridges.

Within seventy-two hours all the Cokes were gone, but no one touched the bills. We human beings are ready and willing to steal something that does not explicitly reference monetary value. However, we shy away from directly stealing money.

The next version of the matrix experiment is also one that we have met before.

- Participants were paid in tokens, which were converted into dollars at a second table 12 feet away.

Those who lied for tokens that a few seconds later became money cheated by about twice as much as those who were lying directly for money.

Dan is surprised by and worried about this result:

The more cashless our society becomes, the more our moral compass slips. What will happen as financial products become less recognizably related to money (stock options, derivatives, and credit default swaps)?

Over-billing

Dan contrasts over-billing by lawyers and consultants to the theft of his GPS from his car.

In terms of its economic impact on my financial future, this crime had a very small effect. On the other hand, think about how much my lawyers, stockbrokers, mutual fund managers, insurance agents, and others probably take from me (and all of us) over the years by slightly overcharging, adding hidden fees, and so on.

I agree with Dan about fees and strive constantly to keep mine as low as possible.

- But I can’t equate the exaggeration common to almost every human with the action of breaking into a car to steal.

Locksmiths

Dan quotes a locksmith who quickly unpicked a lock belonging to one of his students:

One percent of people will always be honest. Another one percent will always be dishonest. The rest will be honest as long as the conditions are right. Locks won’t protect you from thieves, they will only protect you from the mostly honest people who might be tempted to try your door if it had no lock.

Cheating less

The next variation on the matrix experiment – which we have come across before – involved priming subjects by getting them to either remember the ten commandments or ten books they read in high school.

In the group that was asked to recall the Ten Commandments, we observed no cheating whatsoever.

Even though no-one could recall all ten, merely trying to recall moral standards resulted in more moral behaviour.

Similar results were found when atheists swore on a bible before the matrix experiment.

- And when subjects were asked to sign an (imaginary) university honour code.

In contrast to MIT and Yale, Princeton has a strong honour code, including ethics training.

- So Dan carried out some experiments there.

When the Princeton students were asked to sign the honor code, they did not cheat at all (but neither did the MIT or Yale students). However, when they were not asked to sign the honor code, they cheated just as much as their counterparts at MIT and Yale.

So there is no long-term change in ethical behaviour.

- But being reminded of ethical standards at the crucial moment does work.

Tax

In his next experiment, Dan reconfigured the matrix task to look like US tax reporting.

It was stated clearly on the form that their income would be taxed at a rate of 20 percent.

Subjects had to report “income” (problems solved) and also “expenses” (travel time, up to $12) and direct transportation costs (another $12).

- Expenses were exempt from the “tax”.

Controls signed the form at the end.

- Those in the “moral reminder” condition signed the form before filling it out.

The participants in the sign-at-the-end condition cheated by adding about four extra matrices to their score. When the signature acted as a moral reminder, participants claimed only one extra matrix.

The travel expenses followed the same pattern:

“Those in the signature-at-the-bottom condition claimed travel expenses averaging $9.62, while those in the moral reminder condition claimed $5.27.

Dan pitched the idea of signing upfront to the IRS, but they weren’t interested.

Insurance

Dan talked to a large insurance company, who confirmed that most people cheat a little.

Many people who undergo a loss of property seem comfortable exaggerating their loss by 10 to 15 percent.

Dan made a lot of suggestions for improvements to claim forms, but they were vetoed by the lawyers.

However, the company did offer up an odometer reading form as the basis of an experiment.

People who want their premium to be lower might be tempted to lie and underreport the actual number of miles they drove.

Half of the 20K subjects signed at the bottom, and a half at the top.

Those who signed the form first appeared to have driven on average 26,100 miles, while those who signed at the end of the form appeared to have driven on average 23,700 miles. Signatures at the top of forms could act as a moral prophylactic.

Despite this result, the insurance company did not change their form, or indeed any of their forms.

Dan thinks that more surveillance and tougher punishments are not the way to reduce crime.

If we want to take a bite out of crime, we need to find a way to change the way in which we are able to rationalize our actions.

But I think that Dan focuses too much on what most people would call victimless crime.

- He’s interested in cheats, and usually the rich kind, not welfare scroungers.

I want to do away with muggers and burglars and car thieves and rapists and murderers.

- Let’s chuck in people who are cruel to animals, while we’re at it.

Those guys don’t fill in a form beforehand.

Golf

Chapter 2B of the book is about golf.

- I haven’t played the sport since I was a teenager, or even watched since the generation of players I knew retired.

But I think there are strong parallels with investing, though Dan draws a similar analogy with business.

Unlike other sports, golf has no referee, umpire, or panel of judges. The golfer, much like the businessperson [and the investor], has to decide for him- or herself what is and is not acceptable.

Golfers and businesspeople [and investors] must choose for themselves what they are willing and not willing to do, since most of the time there is no one else to supervise or check their work.

Players hit a tiny ball across a great distance, replete with obstacles, into a very small hole. It’s extremely frustrating and difficult, and when we’re the ones judging our own performance, we might be a little extra lenient when it comes to applying the rules.

You can see where I’m heading here.

- If you’ve followed investment blogs or bulletin boards, or financial Reddit or Twitter, you’ll know that the ratio of the expert to the novice or success to failure is eight or nine to one – even if the eight success stories are all using different methodologies.

Unfortunately, you can’t spend internet points, and if you want to be a truly successful investor, you’ll need to be honest with yourself.

- Keep proper score, and ideally, keep an investment diary.

Know when you came out ahead because you were right, and when you were just lucky.

- And just as importantly, learn to recognise when you did the right thing even though you lost money.

Back to golf.

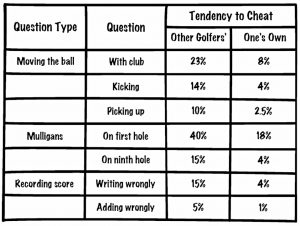

- Dan and a colleague survey 12K golfers in 2009.

They asked them how likely the “average golfer” would be to move their ball by four inches, using either a club, their shoe or their hand.

Dishonesty in golf, much as in our other experiments, is indeed directly influenced by the psychological distance from the action.

More distance/steps between the golfer and the action increased the amount of (imagined) cheating – 23% with the club, 14% with the shoe and 10% with the hand.

The other way to cheat in golf is to allow your self a lot of “mulligans” (do-overs of shots you aren’t happy with).

The survey also asked how likely a player would be to take an illegal mulligan on the first or on the ninth hole.

- On the first hole, it’s easy to rationalise that the second shot is when the game really started.

The golfers estimated that 40% would take a mulligan on the first, but “only” 15% on the ninth.

The third question asked whether a player would record a bogey 6 on a par-5 as a five, or whether they might count it as a five when adding up the total for their round.

- It seems 15% might record the hole incorrectly, but only 5% would add things up badly.

The golfers were also asked the same questions about themselves, rather than the “average golfer”.

- As Dan expected, their dishonesty ratings for themselves were much lower.

It looks to me as though golfers not only cheat a lot in golf, they also lie about lying.

Don’t be like these golfers.

Conclusions

That’s it for today.

- We’re a quarter of the way through the book, so there will be three more articles in this series, plus a summary.

We’ve seen quite a few of the experiments from today in Dan’s previous books – let’s hope these are limited to the early chapters.

- Until next time.