The Honest Truth 2 – Motivation and Temptation

Today’s post is our second visit to Dan Ariely’s third book – The Honest Truth About Dishonesty.

Contents

Motivation

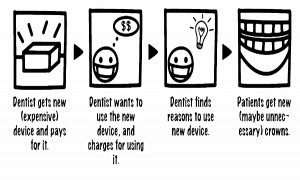

Dan starts Chapter 3 with an extended discussion of the use of CAD/CAM equipment in dentistry.

- Not surprisingly, it exacerbated the general problem in dentistry of over-treatment of non-serious conditions (dentists are paid by the work they do, not by results).

Dan argues that dentists are caring and competent individuals who are led astray by biased incentives.

- I’m going to guess that quite a few (particularly in the US) would rather be doctors, and would like to compete with medics at least in terms of their earnings.

The reality is that conflicts of interest influence our behavior in all kinds of places and, quite frequently, both professionally and personally.

Dan tells a story about when one of his doctors pressure him to tattoo stubble on to the scarred side of his face.

His deputy explained:

He’s already performed this procedure on two patients, and he needs just one more in order to publish a scientific paper in one of the leading medical journals.

One of the things I’ve picked up from the Taleb books is that you should avoid unnecessary interventions in all domains, but particularly in health.

- Only try to fix things that might kill you, or will at least make your life significantly worse.

The same philosophy should be applied to your portfolio – avoid over-trading.

- Whenever you want to make a trade, ask yourself: “What has changed? Why is my existing portfolio not suitable anymore?”

Ideally, use a speed limit – a turnover target for how much you will trade each year.

- I recommend 25% pa.

Moving on to financial services, Dan describes the incentives behind the widespread adoption of mortgage-backed securities before the 2008 financial crisis.

- He thinks that the incentives lead to a fudging of the numbers in the Excel sheets that make the case for such securities.

Academy Award-winning documentary Inside Job describes how the financial services industry paid leading academics to write expert reports in the service of the financial industry.

Dan has personal experience of being conflicted, from when he acted as an expert witness in a legal case.

I rather quickly adopted the viewpoint of those who were paying me. The whole experience made me doubt whether it’s at all possible to be objective when one is paid for his or her opinion.

More generally, a conflict of interests is one of the biggest problems in investment.

- Everyone in the industry wants your money or at least a little piece of it.

Whenever you hear anyone say anything about the markets or the investment process, ask yourself: “Why is he saying that?”

By far the best approach that you can take with investing is to it yourself.

- But most people are scared of money and would like someone to hold their hand.

That’s fine, but you’ll end up much poorer.

Favours

One other common cause of conflicts of interest is our inherent inclination to return favors. When someone lends us a hand in some way or presents us with a gift, we tend to feel indebted.

Political lobbyists and salesmen (eg. drug reps) take advantage of this tendency.

- Free samples and temporary offers are commonplace.

Dan quotes an experiment where subjects reviewed art from within an MRI scanner.

- They were told that one of two galleries had sponsored the experiment (including their payment), and the photos of the paintings came with gallery logos in the corner.

As you might suspect, participants gave more favorable ratings to the paintings that came from their sponsoring gallery.

Perhaps more surprisingly, the MRI scanner showed that the sponsoring logo increased activity in the brain’s pleasure centres.

When participants were asked if they thought that the sponsor’s logo had any effect on their art preferences, the universal answer was “No way, absolutely not.”

The payment for the experiment was varied from $30 to $100 to $300.

Favoritism toward the sponsoring gallery increased as the amount of earnings grew.

And so did the activation in the pleasure centres.

So be careful when you attend those “free” lunches, or cheese and wine evenings, and take no notice of those brochures, pens and USB sticks you receive as “gifts”.

- You may not think that you need to repay your benefactor, but your brain disagrees.

The drunk

Dan recalls an experiment which was turning out the way he expected, apart from one subject.

His performance was much worse than everyone else’s. I remembered that there was one fellow who was incredibly drunk when he came to the lab.

Dan excluded the guy from the data analysis, but then wondered whether he would have done so had he been supporting the result Dan was looking for.

I decided it was okay to create standards for excluding participants from an experiment. But the rules for exclusion have to be made up front, before the experiment takes place.

There’s a lesson here for investment and in particular stock-picking.

- You need to decide on the rules up front, and stock to them.

You can’t decide half-way though to ignore some data that makes the stocks you like (and want to own) look bad.

- More generally, sticking to pre-defined rules in the heat of battle (ie. when the markets are open) ios the way to go.

Disclosure

In theory, full disclosure of conflicts of interest should be a good fix, allowing subjects/clients to make more informed decisions.

- But it doesn’t always work.

Dan describes an experiment where estimators guess how much change is in a large jar.

- They are paid according to how close they are to the real total. (( Disclosure: I once won a huge jar of sweets at a wedding reception by correctly “guessing” how of them there were – 839, I think; full disclosure, I didn’t guess – I counted them, like Rain Man; unfortunately my personal gift comes and goes ))

Advisors instead gave advice to the estimators.

- They were allowed more time to examine the jar, and were told that the total value was between $10 and $30.

In one condition, advisors were paid according to the accuracy of the estimator’s guesses.

- In the conflict condition, advisors were paid according to the size of the error (in a positive direction only).

The average recommendation from advisors in the control condition was $16.50, but in the conflict condition, it was more than $20.

The third condition was the conflict with disclosure.

- Now the advisors recommended $24.16 – $4 higher.

The estimators knew to apply a discount to advice from a conflicted advisor, but the average discount was only $2, so the guesses (and the advisor payments) increased in value.

- A disclosed-and-conflicted advisor is worse than a merely conflicted one!

The takeaway is: do not use an advisor (by which I mean anyone who profits from the specific investment decisions you make).

Recommendations

The best plan is to remove conflicts of interest.

In the medical domain, we would not allow doctors to treat or test their own patients using equipment that they own. We would also prohibit doctors from consulting for drug companies or investing in pharmaceutical stocks.

It’s not easy, and the same goes for fixing conflicts for lawyers, builders, electricians, plumbers and car mechanics.

Alternatively:

When we face serious decisions in which we realize that the person giving us advice may be biased, we should spend just a little extra time and energy to seek a second opinion from a party that has no financial stake in the decision.

In the financial domain, (percentage) fees based on AUM would have to go.

- I have long argued for capped annual fees (like a Netflix or Amazon Prime subscription), but industry professionals laugh in my face.

And ideally, managers and salesmen should be invested in the same assets as you.

- This won’t be easy since allocation varies by age, wealth and risk profile – but they should have at least a consistent framework which shows how they ended up where they are, and why you should have what they are recommending.

The same philosophy should apply to financial bloggers, too – I am in an extreme minority that regularly publishes the allocation of my entire net worth.

As Taleb says:

Don’t tell me what you “think” – show me your portfolio.

Temptation

On stressful days many of us give in to temptation and choose less healthy alternatives [for takeout food].

Chapter 4 leads us to the territory of thinking fast and slow.

- We have two brain systems – quick and lazy, and slow and methodical.

Guess which one likes Chinese food and pizza?

- Dan quotes the story of Odysseus tying himself to the mast so that he could ignore the song of the sirens.

It’s not just tiredness that leads us into temptation.

- We merely need to occupy/distract the methodical system with “cognitive load”.

Dan describes an experiment where half the subjects were asked to remember a 2-digit number, whilst the other half had to remember a 7-digit number.

- They were paid only if they remembered the number at the end.

To get from the room with the number to the room with the money, they had to walk down a corridor past a cart with fruit and cake.

- They had to choose a snack on the way down and write it on a chit that could be exchanged for the snack once they had been paid.

Those remembering a 2-digit number were much more likely to choose fruit over cake.

Ego depletion

Resisting temptation takes considerable effort and energy. Think of your willpower as a muscle.

It gets tiring, and eventually, you stop doing the good stuff and start doing the bad stuff.

- For Dan, this means eating a bad meal in the evening.

Ego depletion also helps explain why our evenings are particularly filled with failed attempts at self-control – after a long day of working hard to be good, we get tired of it all.

Dan quotes a study which shows that parole boards are more lenient when refreshed.

Over the many difficult decisions of the day, as their cognitive burden was building up, they opted for the simpler, default decision of not granting parole.

The same principles apply to investment.

- A lot of the good stuff is hard (too much math) or boring (too much reading).

I have two ways of coping with this.

- I plan for my next burst of willpower (usually the next morning) during the previous evening when I am too tired to behave well

- I “eat the frog” (do the most difficult task) first, while I still have plenty of willpower.

Moral mucscle

Might people who overtax themselves in one domain end up being less moral in others? Would they predict that they are more likely to succumb to temptation and therefore try to avoid the tempting situation altogether?

Dan and his colleagues asked one group of subjects to write a short essay about their activities the previous day, but without using the letters “x” and “z.”

- The other could not use “a” and “n” – a much harder task, which ought to lead to greater depletion.

After this, both groups took the matrix shredder test.

- In the matrix control group, both depleted and non-depleted subjects answered the same number of questions.

But when they could cheat (by shredding their answer paper and lying):

Those who wrote essays without the letters “x” and “z” indulged in a little bit of cheating, claiming to solve about one extra matrix correctly.

But the ones forbidden to use “a” and “n” claimed an extra three matrices.

- So the more depleting the prior task, the more people cheat (in frequency and extent).

Congruent colours

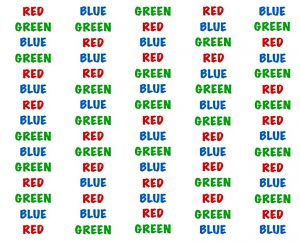

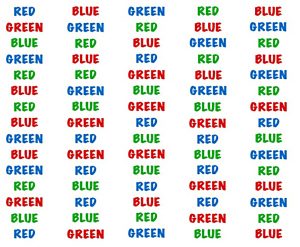

The next version of cognitive load that Dan studied was the use of congruent and incongruent colour words – that is, words printed in either the colour of the word itself or in a different colour.

- This is known as the Stroop task.

There are 75 words on the card, arranged in 15 rows of five.

- Each word is either red, green or blue (in no particular order).

Subjects have to read the word aloud, according to the colour of its ink, not what is written.

- If they make a mistake, they must repeat that word.

Reading the congruent list took around sixty seconds, but reading the incongruent list was three to four times more time-consuming.

After the Stroop test, subjects took a 50-question multiple-choice quiz about Florida State University.

- They were paid according to how many answers they got right.

But they could transfer their answers to a scoring sheet, and shred the answers (allowing for cheating).

- And in fact, they are given the option of taking an answer sheet where the correct answers have been filled in and poorly erased.

The spiel here is that one more person after them must be tested, and there is only one clean answer sheet.

- So either they take the one with the answers, or somebody else gets it.

The depleted participants were more likely than nondepleted participants to choose the sheet that tempted them to cheat.

And (as we saw in the previous experiment) they also cheated more when cheating was possible. We paid the depleted participants 197 percent more than those who were not depleted.

Recommendations

We would be well served to realize that we are continually tempted throughout the day and that our ability to fight this temptation weakens with time and accumulated resistance.

So if you want to diet, don’t keep any bad food in the house.

We should face the situations that require self-control – a particularly tedious assignment at work, for example – early in the day, before we are too depleted.

This is the “eat the frog” rule.

Once we realize that it is very hard to turn away when we face temptation, we can recognize that a better strategy is to walk away from the draw of desire before we are close enough to be snagged by it.

So avoid temptation entirely, rather than tiring yourself out fighting it.

Conclusions

That’s it for today.

- We’re halfway through the book, so there will be two more articles in this series, plus a summary.

Until next time.