The Honest Truth 3 – Fakes, Cheating Ourselves and Creativity

Today’s post is our third visit to Dan Ariely’s third book – The Honest Truth About Dishonesty.

Contents

Fakes

Dan starts Chapter 5 with a discussion of fashion as a form of external signalling.

We broadcast to others who we are by what we wear. Ancient Roman law dictated who could wear what, according to their station and class.

It was the same in medieval England.

Some groups were further differentiated so as not to be confused with “respectable” people. Prostitutes had to wear striped hoods to signal their “impurity,” and heretics were sometimes forced to don patches decorated with wood bundles to indicate that they could or should be burned at the stake.

Dan equates not wearing these signals as a disguise and compares this to wearing fake sunglasses.

- In other words, lying to those around you.

And the lying devalues the signal:

If a bunch of people buy knockoff Burberry scarves for $10, others might not be willing to pay twenty times more for the authentic scarves.

Dan also thinks that what we wear is a form of self-signalling:

Despite what we tend to think, we don’t have a very clear notion of who we are. We observe ourselves in the same way we observe and judge the actions of other people – inferring who we are and what we like from our actions.

So someone who gives money to a beggar will see themselves in the future as more compassionate and charitable.

- It’s a self-reflective version of virtue signalling.

So Dan wondered if wearing fakes might make us feel less authentic.

- And therefore more likely to cheat.

Dan and his colleagues gave female MBA students a pair of real Chloe sunglasses.

- In the authentic condition, they were told the sunglasses were real.

- In the fake condition, they were told they were fake.

- In the no-information condition, they weren’t told anything.

After walking around in the sunglasses for a short while, the women took the matrix test.

“Only” 30 percent of the participants in the authentic condition reported solving more matrices than they actually had, 74 percent of those in the fake condition [cheated]. The no-information condition was between the two [42%], but it was much closer to the authentic condition.

Wearing a genuine product does not increase our honesty (by much). But once we knowingly put on a counterfeit product, moral constraints loosen to some degree.

What-the-Hell

The “What-the-hell” effect is that feeling you get when you break your diet with the first bit of cake (or a dry spell with “just one beer”).

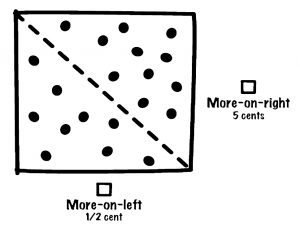

The task Dan used to investigate this was the dots task.

- Subjects look at a square on a screen which is divided diagonally into two fields.

Their job is to decide whether there are more dots on the left or the right.

- There are always 20 dots in total, so the task can be easy (13:7, or even better) or difficult (11:9).

There are a hundred trials, followed by a hundred more.

- The subjects are paid for the second set – 5 cents when a right-hand button is pressed (indicating more dots on the right) but only half a cent when the left button is pressed.

This creates a conflict of interest since when there are more dots on the left, the subjects will be paid more if they lie.

- In this specific experiment, subjects were wearing the sunglasses from the previous test.

Our dots task showed the same general results as the matrix task, with lots of people cheating but just by a bit. The amount of cheating was especially large for those wearing the fake sunglasses.

Counterfeit wearers cheated more across the board – when it was hard to tell which side had more dots, and even when it was clear that the correct answer was more on the left.

But the point of the test was to see how cheating evolved over time.

- Dan suspected that people would only cheat a little to begin with (trying to keep hold of the idea that they were basically honest).

But at some point, they would abandon this pretence, and cheat more (or perhaps at every available opportunity).

The amount of cheating increased as the experiment went on. We also saw that for many people there was a very sharp transition where they suddenly graduated from engaging in a little bit of cheating to cheating at every single opportunity.

Which is the What-the-Hell effect in action.

But the wearers of the fake sunglasses showed a much greater tendency to abandon their moral constraints and cheat at full throttle.

Suspicions

Dan also wondered whether wearing fakes might make people more suspicious of others.

- The next experiment asked subjects (wearing the sunglasses) to fill in a survey about honesty in other people.

The survey included questions about people the subject already knew, a section on common excuses, and a couple of scenarios where people could choose to engage in shady activities.

- In all three sections, those wearing the fake shades were more likely to view others as less honest.

Back to fashion

So the problem with fashion fakes is not so much the loss of revenue to high-end firms (since those buying fakes usually can’t afford the real thing).

- Rather it is the moral decay that fakes induce in their wearers.

From the investor’s point of view, this can bee seen as part of the cockroach problem – there’s never just one cockroach.

- The “broken window” theory operates on similar principles – if you don’t fix the first window, more will soon be broken.

Once a company (or a person) starts to lie (or let you down relative to promises and forecasts) you should expect the lies to continue.

- Hence the market saw “Profit warnings come in threes”.

Dan notes that academic qualifications are a common area for executives and other leaders to lie about.

- And that one act of cheating will raise an executive’s self-signalled level of dishonesty.

We tend to forgive people for their first offense with the idea that it is just the first time and everyone makes mistakes.

But that’s a bad idea.

Cheating Ourselves

Dan begins Chapter 6 with a discussion of how (male) animals puff themselves up (physically and psychologically) in order to beat off the competition and win the best mates.

- Humans have the additional technique of lying, including to ourselves.

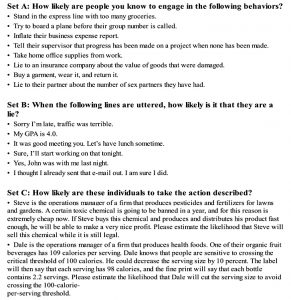

Dan and his colleagues gave subjects a questionnaire like an IQ test.

- Half of the subjexts received a sheet with an answer key, to allow for cheating.

As usual people cheated a bit, but not a lot.

- But what Dan wanted to know was whether the cheaters were deceiving themselves as well.

After cheating, would cheaters think they actually had the intellectual abilities they had reported?

So after the first test, subjects were asked to predict how well they would do on a repeat test (with new questions).

- And of course, cheats predicted they would do as well next time.

In a third version of the test, subjects were paid up to $20 based on how close their prediction came to their score on a second test.

- But still the cheaters took full credit for their exaggerated scores.

One issue I have with this experiment is that Dan doesn’t address the possibility that subjects expected to have the same opportunity to cheat in the second test.

- If they believed this, then regardless of self-deception, the would expect their second score to be as high as their first.

Dan notes that people are often unsurprised by the results of his experiments, even when he himself was at the time of the study.

- This is of course the hindsight bias.

Investors can counter this by writing down what they think will happen before each trade, in a trading diary. (( My blog serves a similar purpose for me ))

- Dan has learned to get people to predict the result of an experiment before he reveals it.

Dan repeated his experiment with an extra test of whether subjects were likely to turn a blind eye to their failures.

We asked participants to agree or disagree with a few statements, such as “My first impressions of people are usually right” and “I never cover up my mistakes.”

Lots of people sad yes, and they had the highest predictions of their own performance on the second test.

Public lies

Dan notes that the last dozen people described by the press as America’s “last surviving Civil War veteran” were all fakes.

- There are also lots of more recent examples of war records in Afghanistan and elsewhete being exaggerated.

Could it be that when we lie publicly, the recorded lie acts as an achievement marker that “reminds” us of our false achievement and helps cement the fiction into the fabric of our lives?

To test this, Dan gave cheats on one of his maths tests a certificate which emphasised their (fake) achievement.

- Controls received no certificate.

The participants who received a certificate predicted that they would correctly answer more questions on the second test.

In the next version of the test, Dan used a version of the “Ten Commandments” honesty nudge we met earlier.

He swapped the paper version of the test for a computerised one, where the answer-key was on a pop-up footer, revealed only on mouse-hover.

- This made subjects think about when and how they were using the answer key.

This time around they did not overestimate their performance in the second test. They still cheated, [but] consciously deciding to use the answer key eliminated their self-deceptive tendencies.

So we need to be made aware that we are cheating, or else we will assume we are “better” than we really are.

- I think this explains a lot about those people who get fat despite “eating almost nothing”.

Dan suspects that self-deception – like overconfidence and optimism – can be useful.

An unjustifiably elevated belief in ourselves can increase our general well-being by helping us cope with stress; it can increase our persistence while doing difficult or tedious tasks; and it can get us to try new and different experiences.

But since we may wrongly assume that everything will be fine, we may make sub-optimal decisions.

- And telling lies can end badly when they are found out.

Dishonesty on our part also leads to mistrust of others, which has its downsides.

As investors, we need to walk a tightrope between optimism (markets always go up again in the end) and realism (perhaps this blue-sky stock will never make a profit).

White lies

White lies involve expanding the “fudge factor”, but not for our own benefit.

- Dan has personal experience of these from, when i=he was a teenage burn victim.

From the beginning, the doctors and the nurses kept telling me, “Everything will be okay.” And I wanted to believe them.

After about a year, a nurse asked him to meet a recovered burn victim.

When the visitor came in, I was horrified. The man was badly scarred–so badly that he looked deformed. This image was far from the way I imagined my own recovery, my ability to function, and the way I would look once I left the hospital.

So the meeting depressed Dan.

On the other hand, they often lied to him about the amount of pain involved in future procedures, which he appreciated.

- In addition, this avoided stressing his immune system from worry, and so helped his recovery.

So in the end, I came to believe that there are certain circumstances in which white lies are justified.

Creativity and Dishonesty

Chapter 7 explains that we are all storytellers.

Dan tells of an experiment where women were asked which pair of four sets of stockings they preferred.

- Generally, they preferred the one on the right, but they mad up a wide variety of stories to explain why.

In reality, all the stockings were the same, and the women preferred the pair on the right simply because of their position.

- Even when this was explained to them, the women denied it.

We may not always know exactly why we do what we do, choose what we choose, or feel what we feel. But the obscurity of our real motivations doesn’t stop us from creating perfectly logical-sounding reasons.

We want explanations for why we behave as we do and for the ways the world around us functions. We tell ourselves story after story until we come up with an explanation that we like and that sounds reasonable. When the story portrays us in a more glowing and positive light, so much the better.

Or as Richard Feynman said:

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.

The moral is – particularly as investors – never be afraid to admit that you don’t know the answer.

Instead, work out a range of possibilities or options, and assign probabilities to them.

- Now what looks like the best course of action?

Cheating yourself

Dan tells the story of when a website interpreted his responses to questions about cars by recommending a boring sedan when what he wanted was a convertible.

I did what any creative person might do: I went back into the program and “fixed” my previous answers until the program was kind enough to recommend a small convertible.

Sometimes (perhaps often) we don’t make choices based on our explicit preferences. Instead, we have a gut feeling, and we go through a process of mental gymnastics to manipulate the criteria.

This comes back to the idea of pretending to ourselves and others that we are honest and rational people when we are not.

Liars

Dan describes an experiment where pathological liars were compared to normal people using a brain scanner to look at the prefrontal cortex (in charge of things like planning and dealing with temptation, as well as moral decision-making).

They found that pathological liars had 14 per cent less grey matter than the control group, a common finding for many psychologically impaired individuals. Pathological liars had 22 to 26 per cent more white matter.

Grey matter is the neurons that do the thinking, and white matter is the wiring that connects the neurons together.

One possibility is that since the pathological liars had fewer brain cells fueling their prefrontal cortex (an area crucial to distinguishing between right and wrong).

With more white matter pathological liars are likely able to make more connections between different memories and ideas, and this increased access to the world of associations might be the secret ingredient that makes them natural liars.

More connected brains have more avenues to explore when it comes to interpreting and explaining dubious events–and perhaps this is a crucial element in the rationalization of our dishonest acts.

Dan hypothesised that there might be a link between creativity and lying.

- Subjects were given a survey of filler questions mixed with three core topics:

We asked the participants to indicate to what degree they would describe themselves using some “creative” adjectives (insightful, inventive, original, resourceful, unconventional, and so on).

We asked them to tell us how often they engage in seventy- seven different activities, some of which require more creativity and some less (bowling, skiing, skydiving, painting, writing, and so forth).

We asked participants to rate how much they identified with statements such as “I have a lot of creative ideas,” “I prefer tasks that enable me to think creatively,” “I like to do things in an original way.”

After that, they tokk the dots task.

Participants who clicked the more-on-right button (the one with the higher payout) more often tended to be the same people who scored higher on all three creativity measures.

Moreover, the difference between more and less creative individuals was most pronounced in the cases where the difference in the number of dots on the right and left sides was relatively small.

So creatives are more prone to lie when there is more ambiguity, and thus more potential justification.

The link between creativity and dishonesty seems related to the ability to tell ourselves stories about how we are doing the right thing, even when we are not.

Intelligence

What if a third factor such as intelligence was the factor linked to both creativity and dishonesty?

Dan references Ponzi schemer Bernie Madoff and cheque forger Frank Abagnale (Catch Me If You Can) as clever cheats.

In the next version of the experiment, subjects took the survey at home before visiting the lab.

- As well as the creativity questions, they were given tests of verbal and logical intelligence (interesting that spatial and numerical tests were omitted).

When the subjects get to the lab, they are told:

You’ll be taking part in three different tasks today; these will test your problem-solving abilities, perceptual skills, and general knowledge.

The problem-solving task is the matrix task.

- The perceptual skills task is the dots test.

- Then there’s a 50-question multiple-choice quiz.

In the end, subjects transfer their answers to a pre-marked bubble sheet, allowing cheating.

What did Dan find?

Individuals who were more creative also had higher levels of dishonesty. Intelligence, however, wasn’t correlated to any degree with dishonesty.

Revenge

Dan describes the “phone-call interruption” experiment we met in his previous book.

- Annoyed subjects in a coffee shop extracted revenge by cheating more Taking more money).

Dan adds a personal story of how he and a friend took revenge against “Italy” for money stolen while they were inter-railing by adding extra permissible routes to the map attached to their ticket.

I’m sure that being in a foreign country by ourselves for the first time helped us feel more comfortable with the new rules we were creating. Second, losing a few hundred dollars made us feel that it was okay for us to take some revenge.

Third, since we were on an adventure, maybe we felt more morally adventurous too. Fourth, we justified our actions by convincing ourselves that we weren’t really hurting anything or anyone. The trains were never full, so we weren’t displacing anyone.

The number of possible justifications persuades Dan that rationalisation is very prevalent in everyday life.

We have an incredible ability to distance ourselves in all kinds of ways from the knowledge that we are breaking the rules, especially when our actions are a few steps removed from causing direct harm to someone else.

Art thieves

As Picasso said:

Good artists copy, great artists steal.

From Shakespeare to Steve Jobs, a lot of popular guys had stolen a lot of the ideas they are famous for.

Dan wanted to know whether he could increase the level of cheating by putting people into a creative frame of mind via priming.

- He added a “practice round” where subjects create sentences from a jumbled list of words.

Each subject gets 20 lists of 5 words and has to make up four-word sentences.

- But there are two sets of words.

One version is the creative set, in which twelve of the twenty sentences include words related to creativity (“creative,” “original,” “novel,” “new,” “ingenious,” “imagination,” “ideas,” and so on).

The control set has no creative words.

After the sentence task, subjects play the dots task (for money).

- There was no difference in performance on the sentence task, but:

The participants who had been primed with the creative words chose “right” (the response with the higher pay) more often than those in the control condition.

In a follow-up experiment, Dan compared the moral flexibility of employees (as measured by a questionnaire) in various departments within an advertising agency to the level of creativity expected in their roles.

The level of moral flexibility was highly related to the level of creativity required in their department and by their job. It seems that when “creativity” is in our job description, we are more likely to say “Go for it” when it comes to dishonest behavior.

Conclusions

That’s it for today – we’ve covered a lot of ground.

- We’re three-quarters of the way through the book, so there will be one more article in this series, plus a summary.

Until next time.