The Psychology of Money 1 – Crazy, Luck, Enough & Compounding

Today’s post is our first visit to a recent book – The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel.

Psychology of Money

Morgan Housel is a partner at Collaborative Fund and a former columnist at The Motley Fool and The Wall Street Journal.

The book is structured as 20 chapters, each covering a counterintuitive feature of the psychology of money.

Morgan starts the book with the story of a rich jerk who stayed at a hotel where Morgan worked his way through college as a valet.

- The guy lost his money in the end.

The premise of this book is that doing well with money has a little to do with how smart you are and a lot to do with how you behave. And behavior is hard to teach, even to really smart people.

A genius who loses control of their emotions can be a financial disaster. Ordinary folks with no financial education can be wealthy if they have a handful of behavioural skills.

The next story is about Ronald James Read, a janitor and gas station attendant who died worth more than $8M because of his blue-chip stock market investments.

- In contrast, Merrill Lynch exec Richard Fuscone blew through all his money, over-borrowing to expand his large home and to throw lavish parties.

The conclusion Morgan draws is about finance:

In what other industry does someone with no college degree, no training, no background, no formal experience, and no connections massively outperform someone with the best education, the best training, and the best connections?

Why is this?

Financial success is not a hard science. It’s a soft skill, where how you behave is more important than what you know. I call this soft skill the psychology of money.

Which is what the book is about.

Morgan plans to convince us using anecdotes, my least favourite form of book content.

- He’s not against maths, but he thinks that the problem with finance is that people won’t/don’t do the things they should.

This is true, but I doubt that reading through a lot of stories will change that.

Morgan thinks that all the brainpower devoted to finance in recent decades hasn’t led to us being better investors.

- I have to disagree.

This is a golden age of DIY investing, with cheap and easy access to a wide variety of products, plus lots of free information on the internet.

- And in the UK at least, the tax regime has rarely been more favourable.

In terms of widespread adoption of good practices, he has a point.

- But the root cause here is easy credit, and the drive from social media to live in the present rather than save and plan for the future.

Finance isn’t to blame, and understanding the psychology behind our most common shortcomings is unlikely to fix them for most people.

- Greed and fear aren’t going anywhere soon.

No one is crazy

People from different generations, raised by different parents who earned different incomes and held different values, in different parts of the world, born into different economies, experiencing different job markets with different incentives and different degrees of luck, learn very different lessons.

This is true enough, but I’m not sure it helps.

- There are objectively good and bad ways to invest, and people who learned the wrong lessons in their childhoods need to unlearn them – and transplant in the good lessons.

Morgan uses the example of living through the Depression.

- The majority of those people were scared away from the stock market for life – but that’s not a good thing.

Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that people’s lifetime investment decisions are heavily anchored to the experiences those investors had early in their adult life.

Inflation puts you off bonds, and a stock market boom makes you keen on equities.

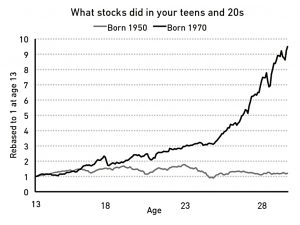

Here’s a chart of the stock market experience for those born in 1950 and 1970:

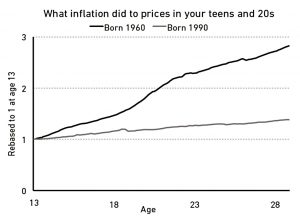

And here’s inflation for people born in 1960 and 1990:

Unemployment is a similar story.

Morgan points out how sweatshop conditions in China don’t seem so bad to the workers there, and notes that the poorest people buy most of the lottery tickets.

He also notes that the concept of retirement – and having to save for it – is relatively new (people used to work until they dropped).

- The same goes for widespread college attendance (and the accompanying debt).

I haven’t loved this opening chapter – Morgan’s description of how and why people make bad financial decisions rings true, but I don’t know what to do with it.

- Are readers supposed to accept their lot, rather than educate and train themselves to make better ones?

I think a better title might be “we’re all crazy for different reasons, but we should still fix it”.

Luck and risk

Chapter 2 is about luck.

Morgan starts with the story of how Bill Gates and Paul Allen were lucky enough to have access to a computer during high school.

- The odds were 1M to 1 against.

Bill’s best friend at the school was Kent Evans, not Paul Allen.

- But Kent died in a mountaineering accident before he graduated, and Bill founded Microsoft with Paul Allen.

The odds of dying on a mountain in high school are also around 1M to 1.

For every Bill Gates there is a Kent Evans who was just as skilled and driven but ended up on the other side of life roulette.

It’s a nice story, but:

- Kent was killed on a mountain.

- We didn’t go mountaineering at my school – some risks are avoidable.

- Just because Kent and Bill were close in high school doesn’t mean they would have turned out the same 50 years later.

Of course, luck plays a role in everyone’s life, but the longer life goes on, the smaller that role (for the majority of people, away from the extreme outcomes).

Bad decisions can lead to good outcomes and vice versa.

- But more often than not, the opposite happens.

If you stick to a plan and trust your process, you can reduce the role of luck.

Morgan tells the stories of Vanderbilt and Rockefeller (both of whom flouted “outdated” laws) and of Ben Graham, whose investing success largely stemmed from a rule-breaking outsize position in GEICO. He said:

One lucky break, or one supremely shrewd decision—can we tell them apart?

Another example is Zuckerberg. He was praised for turning down Yahoo’s buyout offer, but Yahoo itself is now criticised for turning down Microsoft.

- One decision worked out well and the other one didn’t.

Bill Gates said,

Success is a lousy teacher. It seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.

Morgan’s conclusion is:

Be careful who you praise and admire. Be careful who you look down upon and wish to avoid becoming.

He warns us not to focus on individuals, but instead on broad patterns.

- Which brings me back to my dislike of anecdote.

Never enough

According to Morgan, Joseph Heller had enough money, and Rajat Gupta (who he?) didn’t.

- Gupta wanted to be a billionaire, turned to insider trading and went to prison.

A better version of the same story might involve Michael Milken, or Bernie Madoff (who Morgan does mention next).

The question we should ask of both Gupta and Madoff is why someone worth hundreds of millions of dollars would be so desperate for more money that they risked everything in pursuit of even more.

It’s a good question, but lacking both the hundreds of millions and the opportunity, I don’t feel qualified to answer.

- And since I am unlikely to be in that situation, I wouldn’t get too much from the answer if it were available.

I know my number, and I quit work when I hit it.

- Morgan says that the hardest financial skill is stopping the goalposts from moving, but I didn’t find that to be the case.

- You just have to stop caring what the Joneses think.

Morgan also mentions the fall of LTCM, but that’s slightly different.

- Those guys got the maths wrong and took on too much risk.

- They weren’t criminals.

Compounding

Morgan’s first example of compounding is ice ages and the solar cycle.

It begins when a summer never gets warm enough to melt the previous winter’s snow. The leftover ice base makes it easier for snow to accumulate the following winter, which increases the odds of snow sticking around in the following summer, which attracts even more accumulation the following winter.

Perpetual snow reflects more of the sun’s rays, which exacerbates cooling, which brings more snowfall, and on and on.

And the same thing happens in reverse:

An orbital tilt letting more sunlight in melts more of the winter snowpack, which reflects less light the following years, which increases temperatures, which prevents more snow the next year, and so on.

The big takeaway is that you don’t need tremendous force to create tremendous results.

Buffett is the second example:

As I write this Warren Buffett’s net worth is $84.5 billion. Of that, $84.2 billion was accumulated after his 50th birthday. $81.5 billion came after he qualified for Social Security, in his mid-60s.

Longevity is key to his outsize success.

Had he started investing in his 30s and retired in his 60s, few people would have ever heard of him. His skill is investing, but his secret is time.

Morgan points out that Jim Simons has a higher compounding rate (three times as good, in fact), but didn’t get into his stride until he was 50 years old.

But as Morgan points out:

None of the 2,000 books picking apart Buffett’s success are titled This Guy Has Been Investing Consistently for Three-Quarters of a Century.

And:

Good investing isn’t necessarily about earning the highest returns, because the highest returns tend to be one-off hits that can’t be repeated. It’s about earning pretty good returns that you can stick with and which can be repeated for the longest period of time.

Amen to that, and to avoiding serious losses.

That’s it for today.

- We’ve covered around 20% of the book, so there will be another four articles in this series.

I find the anecdotal style of the book frustrating, and I have no takeaways from today.

- But to the casual reader new to the psychological aspects of finance, I imagine it would be quite entertaining.

Until next time.