The Psychology of Money 4 – Errors, Change, Price & Other People

Today’s post is our fourth visit to a recent book – The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel.

Room for error

Chapter 13 starts with a description of card counting in blackjack, and how it allows room for error since the probabilities (based on discarded cards) don’t accurately predict which card will come next.

- Trend-following is similar – you have no idea which bets will be profitable, and you expect more than 50% of bets to fail.

Their strategy relies entirely on humility—humility that they don’t know, and cannot know exactly what’s going to happen next, so play their hand accordingly. There is never a moment when you’re so right that you can bet every chip in front of you.

And you need enough of a bankroll to survive the downswings.

- This brings us to the margin of safety.

As defined by Ben Graham:

The purpose of the margin of safety is to render the forecast unnecessary.

Morgan says that we shouldn’t view the world as black and white.

The grey area—pursuing things where a range of potential outcomes are acceptable—is the smart way to proceed.

The benefits come from tail events once more:

Room for error lets you endure a range of potential outcomes, and endurance lets you stick around long enough to let the odds of benefiting from a low-probability outcome fall in your favor. The biggest gains occur infrequently.

Or as Taleb says:

You can be risk loving and yet completely averse to ruin.

Morgan uses Russian Roulette as an example:

The odds are in your favor when playing Russian roulette. But the downside is not worth the potential upside. There is no margin of safety that can compensate for the risk.

As we’ve already discussed, avoiding tail risks is hard:

You can’t prepare for what you can’t envision. If there’s one way to guard against their damage, it’s avoiding single points of failure. Everything that can break will eventually break.

The first point of failure that most people face is their paycheck.

- Which is easily fixed with an emergency fund.

More generally, you need to save at 15% of what you earn.

- There’s no need to know what you will eventually spend it on.

Change

Chapter 14 argues that the difficulty in long-term planning is that people’s goals and desires change over time.

People are poor forecasters of their future selves.

There’s a thing called the End of History Illusion:

The tendency for people to be keenly aware of how much they’ve changed in the past, but to underestimate how much their personalities, desires, and goals are likely to change in the future.

Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert said:

All of us are walking around with an illusion that we have just recently become the people that we were always meant to be and will be for the rest of our lives.

Morgan has two suggestions:

We should avoid the extreme ends of financial planning. [And] we should also come to accept the reality of changing our minds.

Don’t pick extreme frugality or long hours to fund an extravagant lifestyle, and don’t stick with something that you no longer enjoy.

- Avoid sunk costs.

Price

Everything has a price, and the key to a lot of things with money is just figuring out what that price is and being willing to pay it.

The problem is that the price may not be obvious upfront.

The first example Morgan gives is holding stocks.

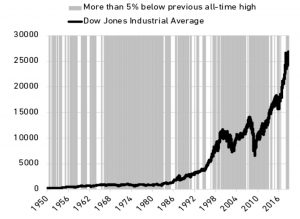

- Stocks have high returns but they crash regularly.

And beyond that, you’re always in a drawdown:

Single stocks are even worse, especially winners like Netflix, Monster Beverage, Apple and Amazon.

So far so good. But Morgan compares attempts to mitigate stock volatility with a strategy of avoiding the price of a new car by stealing it.

They form tricks and strategies to get the return without paying the price. They trade in and out. They attempt to sell before the next recession and buy before the next boom.

I see the damping down of stock volatility as one of my primary tasks in investing.

- I’m not trying to “avoid the price”, I am investing optimally.

Of course, Morgan is right that most people mess up their timing of the market.

- But most people aren’t systematic and rules-based.

And what is the classic 60/40 portfolio (which Morgan defends) if not an attempt to dampen volatility?

You and me

Chapter 16 warns us not to take financial cues from people who might be playing a different game from us.

- Morgan thinks that’s what leads to bubbles.

He starts by revisiting greed as an explanation::

Blaming bubbles on greed and stopping there misses important lessons about how and why people rationalize what in hindsight look like greedy decisions.

I’m not sure that these rationalisations will help, but let’s go with it.

Morgan says that the idea that there is one rational price for an asset makes no sense in a world where investors have different goals and time horizons.

- Timeframes certainly count – fundamentals matter a lot more to long-term investors than to short-term traders.

So if day traders are driving the market, you get the dot com bubble, or the meme stock squeezes of 2021.

The average mutual fund had 120% annual turnover in 1999, meaning they were, at most, thinking about the next eight months. So were the individual investors who bought those mutual funds.

The increasing short-termism of the market is itself a very long-term trend.

This kind of thinking makes less intuitive sense when applied to Morgan’s next example – the mid-2000s housing boom in the US.

- Nobody buying a house should be thinking short-term.

But of course, some do:

It’s hard to justify paying $700,000 for a two-bedroom Florida track home to raise your family in for the next 10 years. But it makes perfect sense if you plan on flipping the home in a few months into a market with rising prices to make a quick profit.

Selling a house must be a bit easier in the States than it is here in the UK.

The formation of bubbles isn’t so much about people irrationally participating in long-term investing. They’re about people somewhat rationally moving toward short-term trading to capture the momentum that had been feeding on itself. Profits will always be chased.

That’s it for today.

- We’ve covered another twenty per cent of the book, and I expect to complete the series in one more article (plus a summary).

It’s been better today, though as usual, I found a few things to disagree with.

- Until next time.