The Psychology of Money 2 – Staying Rich, Tails, Freedom & Cars

Today’s post is our second visit to a recent book – The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel.

Staying Wealthy

Morgan says there is only one recipe for staying wealthy – frugality and paranoia.

- He’s exaggerating, but the gist is true – you have to live within your means and look out for trouble.

He tells the story of Jesse Livermore, made famous in “Reminiscences of a Stock Operator”.

- Jesse shorted the market on October 19th 1929.

In one day Jesse Livermore made the equivalent of more than $3 billion.

Lots of other traders lost fortunes on the same day, and many committed suicide.

- Four years later, Livermore lost his own fortune and eight years after that, he, in turn, committed suicide, broke.

You have to learn how to keep it, not just get it.

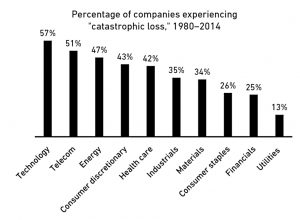

40% of companies successful enough to become publicly traded lost effectively all of their value over time. The Forbes 400 list of richest Americans has, on average, roughly 20% turnover per decade for causes that don’t have to do with death or transferring money to another family member.

The issue is that generally getting the money involves taking risks and being optimistic, whereas keeping it requires avoiding risks and being pessimistic.

- As always, there is a middle course that works long-term – take qualified risks and remain realistic.

Survival is key.

- And compounding takes a long time to show up.

Morgan tells the story of Rick Guerin, Buffett’s other partner.

- He was levered during the 1973-74 crash, and Warren had to buy him out.

So we’ve never heard of him.

A few tips on staying safe:

- avoid (too much) leverage

- keep some cash to prevent distress sales

- don’t aim for the highest returns

- plan, but include room for error and be prepared to adjust course

- be optimistic about the future but paranoid about obstacles

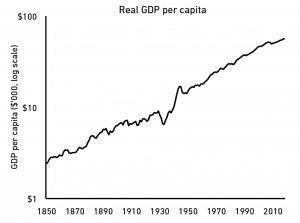

Here are 170 years of US GDP growth:

What you can’t see is:

- 1.3 million Americans died while fighting nine major wars.

- Roughly 99.9% of all companies that were created went out of business.

- Four U.S. presidents were assassinated.

- 675,000 Americans died in a single year from a flu pandemic.

- 30 separate natural disasters killed at least 400 Americans each.

- 33 recessions lasted a cumulative 48 years.

- The number of forecasters who predicted any of those recessions rounds to zero.

- The stock market fell more than 10% from a recent high at least 102 times.

- Stocks lost a third of their value at least 12 times.

- Annual inflation exceeded 7% in 20 separate years.

- The words “economic pessimism” appeared in newspapers at least 29,000 times, according to Google.

The standard of living went up 20-fold, but there was trouble every day.

Tails you win

Chapter 6 is about long tails.

Anything that is huge, profitable, famous, or influential is the result of a tail event—an outlying one-in-thousands or millions event. And most of our attention goes to things that are huge, profitable, famous, or influential.

For example, great art collectors buy a lot of art and sit on it, hoping that a few big winners will pay for all the losers.

- Just like VC, or an index fund.

As Bessembinder has reminded us, all of the returns come from 4% of the stocks.

- Most companies fail.

In 2018, Amazon drove 6% of the S&P 500’s returns. And Amazon’s growth is almost entirely due to Prime and Amazon Web Services, which itself are tail events in a company that has experimented with hundreds of products.

Apple was responsible for almost 7% of the index’s returns in 2018. And it is driven overwhelmingly by the iPhone.

Napoleon’s definition of a military genius was,

The man who can do the average thing when all those around him are going crazy.

Morgan says it’s the same in investing.

The decisions that you make today or tomorrow or next week will not matter nearly as much as what you do during the small number of days when everyone else around you is going crazy.

Such as not selling in a downturn (and ideally adding more money to your pot).

- What did you do in 2009 and 2020?

[Like a pilot], your success as an investor will be determined by how you respond to punctuated moments of terror, not the years spent on cruise control.

Peter Lynch said:

If you’re terrific in this business, you’re right six times out of 10.

And that’s for investing. With trading, you might have four winners out of ten.

- But those winners will be bigger than the six losers.

Morgan makes similar points about big companies trialling failing products, and stand-up comedians trying out unfunny jokes.

- And it’s the same with big investors:

At the Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting in 2013 Warren Buffett said he’s owned 400 to 500 stocks during his life and made most of his money on 10 of them. Charlie Munger followed up: “If you remove just a few of Berkshire’s top investments, its long-term track record is pretty average.”

Freedom

The highest form of wealth is the ability to wake up every morning and say, “I can do whatever I want today.

I agree – in fact, I would say that’s the only definition that makes sense.

Psychologist Angus Campbell studied happiness and concluded:

Having a strong sense of controlling one’s life is a more dependable predictor of positive feelings of wellbeing than any of the objective conditions of life we have considered.

Morgan lists a few less useful alternatives:

More than your salary. More than the size of your house. More than the prestige of your job.

And even:

Doing something you love on a schedule you can’t control can feel the same as doing something you hate.

This is known as reactance.

- Time is money, and conversely, money gives you back control over your time (though sadly at the moment it can’t be used to buy you extra years).

Morgan notes that despite the US being one of the richest countries in the world, a greater than average proportion of its population are worried and stressed.

We’ve used our greater wealth to buy bigger and better stuff. But we’ve simultaneously given up more control over our time.

And jobs have evolved from production labour to services and management.

- The latter in particular, are jobs that you can take home with you.

Cars

When you see someone driving a nice car, you rarely think, “Wow, the guy driving that car is cool.” Instead, you think, “Wow, if I had that car people would think I’m cool.

Well, maybe the steadily shrinking subset of the population who likes nice cars.

People want wealth to signal to others that they should be liked and admired. But in reality, those other people often bypass admiring you, because they use your wealth as a benchmark for their own desire to be liked and admired.

Having stuff doesn’t get people to respect you – ask Jeff Bezos.

- So don’t buy stuff for that reason.

People respect people for the oddest reasons – just look at the most popular characters on social media.

The best plan is to forget about impressing other people at all.

- Focus on impressing yourself.

That’s it for today.

- We’ve covered another twenty per cent of the book, and I expect to complete the series in three more articles (plus a summary).

It’s been a breezy read once more, but I didn’t learn too much about how to invest.

- Until next time.