The Psychology of Money 3 – What you Don’t See, Saving, Being Reasonable & Surprises

Today’s post is our third visit to a recent book – The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel.

What you don’t see

Chapter 9 continues the car theme

- Lots of flash cars are bought with loans (or today, thanks to financial innovation, leased).

We tend to judge wealth by what we see. We can’t see people’s bank accounts or brokerage statements. So we rely on cars, homes, Instagram photos.

This is the “fake it until you make it” approach.

- But of course, most of them never make it.

The truth is that wealth is what you don’t see.

By which Morgan means the things you don’t buy.

There’s a nice quote that Morgan uses without attribution, leading me to believe it could be from Morgan himself:

When most people say they want to be a millionaire, what they might actually mean is “I’d like to spend a million dollars.” And that is literally the opposite of being a millionaire.

Wealth is an optionality for future choices.

- But most people would rather spend the money.

Saving

People fall into three groups: Those who save, those who don’t think they can save, and those who don’t think they need to save.

Chapter 10 starts with the idea that your savings rate is more important than your investment returns.

- The idea is popular in the FIRE community – and the retail finance community – for obvious reasons.

The target customer for both crowds is the 20-something who is just beginning to have some money spare to put away.

- For the FIRE crowd, it’s easier to explain saving than investing, and for the finance crowd, the bigger the pot these guys put together, the more fees they can scrape off the top.

But eventually – usually in your early forties – investment takes over from savings.

Morgan’s basic point is that how much you save is more in your control than how much you earn.

- That’s debatable, and I would certainly recommend that young people max out their potential earnings, but however much you earn, putting 15% or more of it into a retirement pot is crucial.

Savings can be created by spending less. You can spend less if you desire less. And you will desire less if you care less about what others think of you.

Reasonable

Morgan thinks that being reasonable is better than being rational.

- Let’s see if he can persuade me.

Do not aim to be coldly rational when making financial decisions. Aim to just be pretty reasonable. Reasonable is more realistic and you have a better chance of sticking with it for the long run.

Morgan starts by explaining that fevers are generally good for us, but because they are uncomfortable, we treat them anyway.

- He worries that academic finance searches for optimal investment strategies.

In the real world, people do not want the mathematically optimal strategy. They want the strategy that maximizes for how well they sleep at night.

That’s true, but not necessarily a conflict.

- We can optimise for sleeping at night, too.

Morgan tells the story of how Markowitz didn’t follow his own advice on portfolio construction:

I visualized my grief if the stock market went way up and I wasn’t in it—or if it went way down and I was completely in it. My intention was to minimize my future regret. So I split my contributions 50/50 between bonds and equities.

Regret minimisation is an excellent strategy, but note that (1) eventually Markowitz did diversify, and (2) he’s an academic.

So what does Morgan mean by reasonable:

A rational investor makes decisions based on numeric facts. A reasonable investor makes them in a conference room surrounded by co-workers you want to think highly of you, with a spouse you don’t want to let down, or judged against the silly but realistic competitors that are your brother-in-law, your neighbor, and your own personal doubts.

I disagree – you need to jettison the “social component” of investing in the same way that you need to dump the social component of your spending.

Morgan’s next target is life-cycle investing, the idea that young people should borrow to invest in the market, and gradually unwind that leverage through their lives.

- He makes the point that sticking to the strategy through the inevitable early crashes would be almost impossible.

But that doesn’t make it wrong.

- Choose a strategy that you can follow for the long run, but don’t kid yourself that it’s the best strategy, rather than the best one for you.

Morgan also suggests that you love your investments.

- I think this is a dumb idea since you won’t get rid of them when they are no longer a good fit.

I think you should love your plan and your process.

- Individual investments are not something you should be focused on.

Morgan’s point is that all investments go through rough patches, and you shouldn’t necessarily dump them.

- But sometimes you should – the plan is king.

Morgan does allow for a small amount of irrational investing “to scratch an itch”, and so do I.

- It helps psychologically, and depending on your core strategy, it can even lower volatility.

Surprise

Chapter 12 seems to argue against using the past as a guide to the future.

Investors have feelings. That’s why it’s hard to predict what they’ll do next based solely on what they did in the past.

I have to disagree with this.

- Human emotions and psychology are based on hundreds of thousands of years of evolution.

They are unlikely to change because of a few decades of late-capitalist consumerism.

- Fear and greed drive the markets, and they always will.

Morgan, on the other hand, thinks that experience leads to over-confidence.

- I’ll still take experience over the lack of it, thanks.

He also thinks that relying on history means you will miss the tail events – what people like to call black swans.

- Maybe, but pretty much everyone is going to miss the black swans.

What matters is how prepared you are for black swans in general, and how you react.

The correct lesson to learn from surprises is that the world is surprising.

I agree with that much, but it won’t help with investing.

Morgan points out how the structure of financial markets has changed recently.

- He talks about retirement accounts and the growth of VC and tech, and changes to accounting rules.

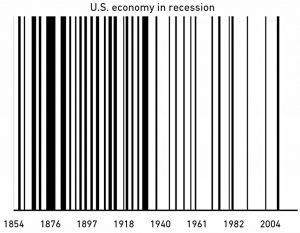

Recessions are further apart (perhaps because of central bank intervention, perhaps because of the move from manufacturing to services):

He also talks about how Ben Graham’s classic investing book The Intelligent Investor has dated badly. (( That book is next on my list to review, so we’ll soon find out ))

Just before he died, Graham said:

I am no longer an advocate of elaborate techniques of security analysis in order to find superior value opportunities. This was a rewarding activity, say, 40 years ago, when our textbook was first published. But the situation has changed a great deal since then.

All this is true, but let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater.

- Generally speaking, things are not “different this time”.

As Morgan says:

The further back in history you look, the more general your takeaways should be. General things like people’s relationship to greed and fear, how they behave under stress, and how they respond to incentives tend to be stable in time.

Hot sectors, value metrics, the best ways to keep costs and taxes low – not so much.

That’s it for today.

- We’ve covered another twenty per cent of the book, and I expect to complete the series in two more articles (plus a summary).

It’s been an interesting read once more, and there was more content relevant to investing today – but there was plenty of stuff to disagree with.

- Until next time.