The Role of Active Investing

Today’s post is about where active investing fits into an investor’s overall strategy, and how that role is changing.

Contents

The goal

I plan to tackle this subject in two articles:

- What are the issues surrounding the passive vs active debate?

- What should a rational investor do about them?

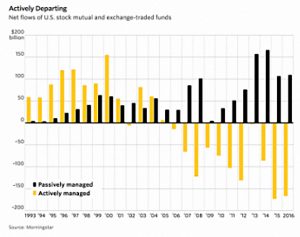

We’ll start with the issues, but first, let’s be clear that passives are winning the battle:

Definitions

Passive funds were invented in the 1970s, but they didn’t become really popular in the UK until after the 2008 financial crisis.

- The subsequent ten-year bull market has been a good period to invest in passives.

So much so that in recent years, passive has come to mean good and active means bad.

- But in fact, the lines are blurred and we need to take care with our definitions.

Essentially, a passive investment is a fund which mechanically tracks an index.

- There are now more indices than stocks.

The tracked index should ideally be published by an independent body (MSCI, FTSE) but some fund managers use their own indices.

- This will usually be to avoid paying the license fee but the tactic could also be used to apply a passive veneer to a proprietary active strategy.

In contrast, an active investment is a fund which has its underlying instruments chosen by a human, on the basis they are good in some way.

- Note that many in the industry restrict the term passive to market cap indices – to them, all other strategies, even if a computer tracks an index, are active.

This human factor is a point of concerns – managers can be lured away by rivals, or suffer from “style creep” as they abandon their published strategy in order to make up earlier losses (Woodford might be a good example here).

And manager incentives aren’t aligned with those of their investors:

- Managers are paid in proportion to the amount of assets they have under management, not the performance of their funds.

Which makes it a marketing-led business, not an investment-led one.

- The entire retail financial industry is not interested in trying to get better at investing.

They are just looking for better ways to win your trust.

Some managers cheat by hogging the index – they are known as closet indexers.

- This is bad because you are paying active prices for a passive product.

You can guard against it by looking at the active share of a fund – this is the amount by which it differs from its sector index.

- This won’t by any means guarantee outperformance, but at least you will be paying for something rather than nothing.

On top of this we need to layer investor behaviour:

- You can passively buy and hold active instruments.

- You can trade passive instruments (ETFs, say).

You can leave your pot alone, or you can add to it each month (in accumulation).

- You can make withdrawals each month or year (in drawdown/decumulation).

You could use “lifestyle” or “target date” funds which increase your bond percentage as you get older.

- It’s a bad idea, and we can all agree that it’s not passive.

You can rebalance back to a target asset allocation each year.

- And you will need to decide what to do with the dividends you receive.

So there are a lot of options to consider.

- A potentially useful distinction is between those who are trying to beat the market and those who are happy to take the (risk-adjusted?) market return.

But really that just kicks the can down the road, because then we need to define what the market return is.

- Market cap indices make a handy ruler because they are cheap and widely available.

But they are not the only possible ruler.

A continuum

I will argue below that there is no such thing as passive investing, and that we are all therefore active investors.

- Nevertheless, there are degrees of activity.

As a framework for what is to come, here’s how I see the continuum of techniques, working up from least active to more active, and then on to suicidal:

- Passive market cap index funds (ETFs or OEICs), with a buy and hold approach and infrequent rebalancing (no more than once a year).

- Risk-parity passive portfolio (of ETFs)

- Actively managed funds (ITs or OEICs) in some appropriate asset classes (PE, VC etc).

- Factor funds (smart beta)

- Hand-crafted mechanical factors (eg. trend-following)

- Individual stocks (home country large-cap only, buy and hold)

- Stock-based factors with judgement (usually value or dividend portfolios)

- Small-cap stocks (including AIM in the UK)

- Leverage – FX (including crypto) and commodities futures and spread bets (shorting)

- Individual foreign stocks (probably US tech at the moment)

- Lottery tickets (oil and gas, mining, blue-sky tech and biotech small caps)

- Day-trading

You might want to argue about the exact location of an item or two on that list, but hopefully, the direction of travel is clear.

- And that’s just for what we could call our listed portfolio.

We also need to work our non-listed assets into our strategy:

- Property, including the home you live in

- DB and state pensions

- Cash

Passive investing

First, let’s clear up the idea that there’s such a thing as passive investing.

- That there isn’t is a concept popularised by Cullen Roche, who writes at the Pragmatic Capitalism (PragCap) blog.

A true passive investor would track the entirety of the world’s assets – but that’s impossible since many of them are not investable, not for sale, and not even valued regularly.

So we could say that we should aim to track the world’s outstanding financial assets – or maybe just the investable assets.

- Cullen calls this the Global Financial Asset Portfolio (GFAP, unfortunately).

We could use market capitalisation for stocks and stock markets (it’s not a great idea – as we’ll see below – but lots of people do it) and buy a world index tracker.

- But what do we do for other assets?

How do we scale the bond market and the commodities markets and the FX markets into this (relative to the size of the stock market)?

- What about real estate?

- How do we net off derivatives contracts?

A further point is that all these asset classes have different levels of average returns, so if we let the market size determine our allocations, we might not get the returns we want or need (spoiler alert – we won’t).

- To fix this you need to set a top-down asset allocation plan.

Which means that we are all active investors, even if we just buy index funds.

What is the GFAP?

Cullen himself takes a fairly simple approach to the GFAP, calling it a 45/55 stock/bond portfolio.

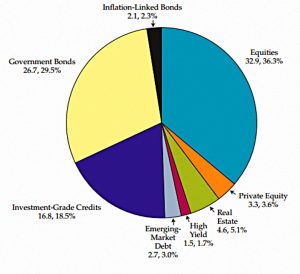

Here’s a more complicated version (from Doeswijk, Lam and Seinkels, via PensionPartners) albeit a few years out of date:

They have 36% stocks, 55% bonds and 9% alternatives.

Saving vs investing

Going back to Cullen, he also says that what we do when we buy stocks and bonds is not even investing.

- We are just reallocating our savings – part of the asset allocation task.

Real investment involves buying things that are used for future production.

- Capex, in other words – so, my buying a computer is more like investing than is my buying an ETF.

And subscribing for primary shares in a company could be seen as (indirect) investing (since the firm you buy the shares in will hopefully invest productively).

- The only time I do this is when I buy VCTs.

- This is third-hand investing since the fund will “invest” in firms which do the actual investing.

Secondary trading of stocks and bonds is not investing.

There’s no real consequence to this distinction, but in the context of where active investing fits in, “saving” or “asset allocation” is clearly lower on the activity scale than is “investing”.

- Savers are not trying to “beat the market” or “get rich quick”.

They are putting aside money (deferring consumption) for the future, and are more likely to be interested in preserving their purchasing power.

Indexing is not average

Cullen’s third myth is that indexing is average.

What he means is that active managers lose (in terms of customer returns) through their fees and higher trading costs (from higher turnover).

- Note that the higher turnover is not guaranteed but that in the US (where Cullen is from) there are also short-term capital gains taxes to think about.

Note also that passive funds can require quite a bit of turnover to track a large index, depending on their replication rules.

- But in general passive costs are lower, which is the point.

So indexing is a bit worse than average, but not so much worse as the average active fund.

- Index funds regularly end up in the top quartile – they are not average in the sense that most people understand.

The maths

The idea that active funds must underperform on average comes from a 1991 paper by William Sharpe called The Arithmetic of Active Management.

Sharpe said:

- Passive investors earn market returns, and

- Active investors play a zero-sum game – for every winner, there is an offsetting loser

- Since active costs are higher, active investors must underperform on average.

Recently this maths has been challenged Lasse Pedersen of AQR in a paper called Sharpening The Arithmetic of Active Management.

- He argues that the original paper’s logic depends on passive investors not trading and that the market never changes.

And when passive investors are forced to trade, they tend to be exploited by active investors.

Are markets getting dumber?

There’s a suggestion from some active managers that markets are getting dumber as more people switch to passive funds (or smart beta).

- This is relevant to our discussion because it speaks to whether pursuing an active strategy is getting harder or easier.

The idea is that passive funds are programmed to act in a certain way when certain things happen (basically when something is added to or dropped from an index, or the ratio of the constituents change).

- And that the higher proportion of market players that are pre-programmed to do the same thing, the more likely it is that this thing will be the wrong thing.

I guess this is a version of the Butterfly Effect.

The counter-argument is that the money that is moving to passive is the “weak hands” or “dumb money”.

- Which leaves a higher proportion of smart money and high skill managers in the active portion of the market, making it ever harder to outperform.

A related point is that many passive investors are not using a “buy and hold” strategy.

- They trade in and out of ETFs, usually underperforming the underlying funds.

This means that the problems some people foresee in a passive-dominated market are less likely to arise.

Dependence

The passive indexers need active investors for two reasons:

- price-setting (of the components in the index)

- liquidity (being the other side of the trade which rebalances the fund back to the index)

In a sense, passive investors are free-loading off the work of active investors.

- Of course, it’s not free, as even indexers pay (low) fees.

- And in fact, most of the rewards from indexing (the bidding up of likely new entrants to an index etc.) go to active investors before the instrument enters the index.

This is one of the problems with market cap indexing (see below).

This relationship raises questions about what would happen if passives dominated to a great extent, but it’s likely that:

- we don’t need many active investors for price-setting, and only a few more for liquidity

- passive dominance would throw up more mispricing opportunities for active investors to exploit, so they would be amply incentivised and rewarded

Can we pick stocks?

Perhaps not all of us, but there is evidence to suggest that active fund managers can pick stocks.

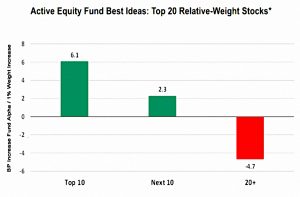

- Take this chart from Enterprising Investor:

The top 10 and the next 10 holdings of funds add value, and the rest destroy it.

- So we want to hold the most concentrated active funds or construct our own portfolio from their largest holdings.

But most active fund managers are prevented from being so concentrated by their mandates.

- This is the first step towards the closet indexing we mentioned above.

Can we pick managers?

This is where it gets tricky.

- Few managers outperform all of the time.

- In particular, recent outperformance often precedes future underperformance.

- It’s hard to identify future outperformers in advance.

- Statistically, you need data from most of a manager’s career before you can prove that he has outperformed.

Future of active investing

Despite:

- the widespread adoption of DIY indexing with Vanguard funds by tech-savvy millennials

- the rise of robo-advisors and nudge savings apps which use ETFs, and

- scandals around the cosy relationship between active funds and the platforms they are bought on (such as the recent Woodford brouhaha)

I believe that traditional active managers – including closet-indexing OEICs – will be around for a long time.

They say that science advances one funeral at a time, and active investing is the same.

- The old guys I meet at investing conferences aren’t giving up their HL accounts stuffed with hero managers.

- And the high-fee product lines are embedded in the corporate pension and insurance company offers.

ETFs will become more popular, and will take over in the end – but it will occur over decades.

- And there will always be some people for whom the promise of “market-beating returns” will justify higher fees.

Conclusions

I’m going to leave it there for today.

- I hope you are convinced that active vs passive is a continuum and that not everyone means the same thing when they use the terms.

In the next post, we’ll look at how all these issues affect our best approach to investment.

- Until next time.