Weekly Roundup, 13th January 2015

We begin the weekly roundup with the FT round table.

Contents

FT Round Table – themes for 2015

The FT got a panel of pundits together to discuss 2015. As well as Merryn, Jonathan Eley and James Mackintosh from the paper, we had Andrew Milligan from Standard Life, Anne Richards from Aberdeen Asset management and Russel Napier, an independent investment strategist.

First up was the falling oil price. RN said this was bad news – falling cash flow would lead to a credit event. The question was whether this would be big enough to disrupt the global financial system. AR saw it in terms of winners and losers, and that winners included those who don’t have financial assets – the “broader real economy” as she called it.

MSW disagreed with AR that the benefits of the recovery hadn’t been widely felt; anyone in continuous employment had done just fine. They never saw a recession rather than never saw a recovery.

AM argued that the low oil price would feed though into the petrol price, putting more money into the pockets of those without financial assets. These people have a greater propensity to consume and so spending should pick up.

The consensus on the low for the oil price was around $40 a barrel.

The next topic was Grexit, which the panel felt would be a disaster. AR pointed out that Syriza wants debt forgiveness not exit. AM thought that a win for Syriza offered support to all the other anti-EU parties and could complicated ECB QE.

JM thought that the Germans might welcome Grexit as a warning to the other southern European states. The panel though that capital controls in the rump of the Euro-zone would be likely.

The third topic was the UK election. AM and MSW were worried a run on sterling possibly triggering early UK interest rate rises. AM and AR felt that the long-term impact of elections was usually minimal but MSW pointed out that this was an atypical election, with a novel coalition a real possibility.

No-one felt that there would be a UK interest rate rise without a run on sterling. RN expected QE to return in the UK and the US by year-end, to counteract deflation.

The US stock-market was felt to be expensive but still worth buying. AR: “You’re buying global earnings, they just happen to be listed in the US”. As long as corporate earnings were rising AM was happy to buy.

The panel was asked to name its one investment for 2015:

- MSW: a vicarage two hours from London as people move out of the capital

- RN: gold-mining shares as exchange controls push up the gold price

- AR: oil plays when the bottom is reached in a few months, possible some emerging markets also

- AM: commercial property

- JM: cash, ready for the capitulation in energy and gold stocks

Retail bonds and the search for income

Elsewhere in the paper, Jonathan Eley looked at the search for income. Low interest rates have pushed investors into riskier assets and the pension reforms in April should push up demand for income-producing assets even further.

The options are:

- Pensioner bonds – limited supply, modest interest rates and taxable

- Three and five year savings accounts – inflexible and taxable

- P2P – decent returns but untested industry (credit quality will be impacted by an increase in lending volumes) and taxable at present

- Buy-to-let – past its best: illiquid, high transaction costs, house prices are stalling, the tax treatment may change (see below)

- Income shares – volatile, best for those with enough money to diversify

- “Mini-bonds” – not tradeable, high credit risk, ineligible for tax wrappers

- Structured products – good yields, but complex, fixed terms and come with counterparty risk and underlying risk of FTSE shares ((Jonathan doesn’t mention listed structured products, which I will cover in a future post))

- Retail bonds – the LSE platform (Order Book for Retail Bonds) makes trading straightforward and yields of 5-6% are available; most can go into ISAs ((I think from memory they need to have 5 years left to maturity)) but they still have counterparty risk

I agree with Jonathan about the attractions of a regulated and liquid tradable product, but I can’t bring myself to buy bonds at the bottom of the interest rate cycle.

I was in the process of putting together a bond ladder when the credit crunch hit in 2008. Seven years later it remains one of those plans for my retirement that I have no idea when or if it will be possible to make come true.

Student property fund liquidation

Still in the FT, Juidth Evans reported on the liquidation of the Mansion Student Accomodation fund, despite the general good performance of student accommodation as an asset class over the past 20 years. Brandeaux Student Accomodation, a similar vehicle, was also suspended in 2013 because it was unable to meet redemption requests.

About £5bn of investors’ money is held in unregulated funds like these which were marketed to retail investors before a crackdown in 2013. Problems with liquidity are always likely with retail investors, who often want their money back at short notice.

I am drawn to specialist property vehicles like these for diversification reasons, but they never seem to work out well (I’m thinking of the problems with care homes a few years back). Probably safest to stick with the major REITs.

Tax treatment of buy-to-let

Over at the sister publication FT Adviser.com, editor Ashley Wassall wrote an opinion piece on the buy-to-let market. He doesn’t think it fair that private landlords have access to mortgages denied to first-time-buyers and low-income “wannabe homeowners”. Hmm … if I remember correctly, encouraging people to buy houses they couldn’t afford was what got us into this mess back in 2008.

Ashley is a young man, and I strongly suspect he has a dog in this fight. I am an older man, and I have the opposite mutt. ((Metaphorically speaking, I don’t own any private sector buy-to-let housing.)) This intergenerational tension is something that worries me. On more and more issues, asset-rich oldies are at loggerheads with debt-burdened renting youngsters.

Houses have been very much in demand in the UK in recent years. We have a rising population, increasing fragmentation of households, and not enough housing being built. We have continued record low interest rates. We also have a unique city in the shape of London which attracts demand from around the globe, displacing locals to the surrounding areas.

Naturally prices have risen strongly (though this cannot continue indefinitely). But housing is just one thing amongst many that are in short supply. Money – including money borrowed against your current financial standing and future prospects – is how we ration things. I would like a Rolls-Royce, but I don’t have one because I can’t afford it. I would like a yacht. I would like a table at the Chiltern Firehouse.

More seriously, I too would like a bigger house in a more central area. Perhaps Ashley could arrange a 50-year £5M loan for me (that I will never get around to repaying). Perhaps not. Unless we are all in favour of massive house price reductions relative to wages, a lot of people are going to have to rent their home in future. And they are going to have to rent it from a buy-to-let investor.

Removing the tax offset for loan interest – which exists because buy-to-let is a business ie. something people do for a living – is an idea that seems to be gathering support, but I can’t agree. It may hurt these investors in the short run, but in the long run they will either pass on the expense to renters, or get out of the market. Which will reduce supply and increase rents again.

We should build more houses. We should encourage people with empty rooms to rent them out. We should think about just how many people we want to have living in the UK. But let’s stop fiddling with property taxes.

The housing market in the UK is crucial to the economic well-being and financial confidence of the country. Poking it with a blunt object could have unintended consequences. Be careful what you wish for.

End of the debt supercycle

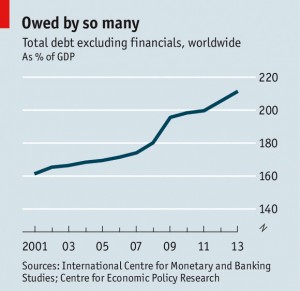

The Economist looked at a report from BCA Research which suggest that the post-war “debt supercycle” is coming to an end. The gradual growth in debt has been largely triggered by monetary easing in response to crises as far back as the 1987 crash. The end is being called not because debt has fallen, but because almost zero interest rates have failed to produce another private sector credit boom.

Before the 2007-8 crash, debt was seen as neutral and zero-sum, but the fact that lost of it is secured to property means that in fact it leads to bubbles. Hyman Minsky argued that easier credit would inflate property prices, encouraging lenders to ease their terms.

When the crash happens, both borrower and lender lose money – things are not zero sum after all. The risk of a credit crunch also increases as overall debt levels (and therefore re-financing levels) increase.

Reducing the debt level in the absence of growth is difficult; defaults just shift debt from the private sector to the public as the government bails out banks. Inflation (not that we have any) would help if yields can be kept low (financial repression).

The question is whether growth can happen without more debt; consumers won’t borrow until they feel rich (real wage rises) and companies in turn will wait for rising consumer demand. Perhaps the oil price crash will have a silver lining.

Negative German bond yields

Over on his blog The Right Side, Bengt took issue with Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman over his interpretation of negative yields on German five-year bonds. Krugman thinks the low yields are a sign of future deflation and euro strength.

Bengt thinks that they reflect the risk that they will be repaid in Deutsche Marks rather than euros, and that Marks will have a higher value. I have to say that for once I like both explanations. At least one of them should happen. I’ll have more to say on deflation next week.

Where Bengt is investing

Bengt also gave us an insight into how he will be investing in 2015:

- he’s slightly positive on equities given the prospect of ECB money-printing

- he’s out of government bonds at these yields (no inflation protection)

- he’s reduced his large holding of corporate bonds (down to 15% now) and will now hold as deflation protection (debt interest is more likely to still be paid than equity dividends)

- commodities and gold had a bad year, but he’s hanging on to them as inflation hedges

- he’s keeping 20-25% cash in case any opportunities arise

This is quite some distance from my own asset allocation, but I find the analysis of risks and solutions useful. We each have to solve the same problems in a way that works for us.

Until next week.