Weekly Roundup, 13th October 2015

We begin’s today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with a look at the flat-rate pension.

Contents

The new state pension

Josephine Cumbo looked at the changes to the state pension, and its implications for those who contracted out, mostly in the 1980s and 1990s. ((Disclosure – I am one of those people ))

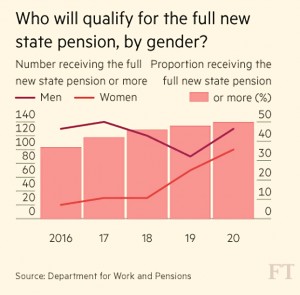

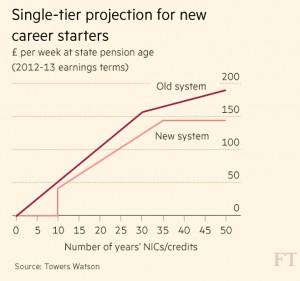

From April 6 2016, a new “flat-rate” state pension of around £155 per week (£8K) begins. In general this is a good thing, as the old system was complicated and worked against women and the self-employed.

The new system works on a simple minimum number of years (35 for a full pension, up from 30) with credits for students and carers etc.

But to begin with, two-thirds of pensioners will get less than the flat rate. This rises to 50% around 2021, but won’t hit 90% for more than 30 years.

The big problem is that the new regime counts NI contributions from the contracted out years as incomplete, since workers paid a lower rate of NI.

Initially this was in return for the state earnings related pension scheme (Serps), which evolved into the state second pension.

The scheme was designed for higher earners to top up their (lower) state pension by contributing to company (DB) or private (DC) schemes, reducing the burden on the state.

One of the constraints placed upon the designers of the new pension was that it should be cost-neutral. So on average, those who contracted out between 1978 and 1997 will receive £55 a week less than the new flat-rate. That’s £3K a year, or £60K over a 20-year retirement.

To make things worse, those who invested in DC top-schemes will have little compensatory income to show from those. ((My own contracted out scheme might produce annual income of around half the projected shortfall ))

There’s no great injustice here, it’s largely a problem of communication. When the new state pension was being sold to the public as a good thing, there was no mention of the fact that two-thirds of people wouldn’t be eligible.

And now that state pension forecasts are dropping through letter boxes, they still don’t include an explanation of how the contracted out deduction is calculated.

Those with more than 35 years of contributions but less than the full rate of pension are particularly aggrieved.

This is the problem with pensions – it can be thirty years after a decision (whether or not to contract out) that you find out it was a bad one.

There is a small silver lining for some. The penalties are being applied as a one-off next year. Everyone has a 2016 “starting rate”.

If you have some working years remaining before you reach state pension age, then further NI contributions (mandatory or voluntary) will increase your pension.

So make sure you get a forecast (( They don’t make this easy – you need to be over 55, then you need to complete a form online, print it out and post it to the government )) and work out whether you need to make extra contributions.

Private pensions

Private pensions were also a big topic this week, as the Government’s consultation on the latest round of tinkering drew to a close.

Merryn wrote about George Akerlof and Robert Shiller’s new book Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=0691168318]

It’s premise is that marketing persuades us to spend now instead of save for our future. As a consequence, governments bribe us to save via tax-relief on pension contributions.

The current system of deferring tax until the money is withdrawn and spent (know as exempt, exempt, taxed, or EET) favours high-rate taxpayers, who get more relief up front. ((On the first £40K pa of contributions – going down to £30K pa next year – and a pension pot no larger than £1M ))

Because of this the system appears expensive when measured in terms of the year 1 tax loss (really a tax deferral).

Merryn thinks the whole system is too complicated. She’s right, but it’s inevitable when dealing with a 50-year product that any changes to the system – there have been many over the past 20 years – will not be applied retrospectively.

Merryn prefers ISAs, which are nice and simple (though less favourably treated under a TEE tax regime).

I think this would lead to less saving overall.

Instead, an ISA with a government top-up – albeit at the same rate for all taxpayers – would achieve the government’s objective of bringing forward tax revenue without impacting the already dreadful savings rate.

Merryn concedes that industry lobbying means that a top-up of around 30% is most likely.

But the best idea would be to leave things as they are, and gradually increase the auto-enrolment contributions level up to around 15%. Then people might actually be able to afford their retirement.

The Economist was also against changes to the pension tax regime.

Governments face a trade-off in designing pensions: long-term reduced dependence on the state vs short-term spending to boost the economy.

Ideally they want a pensions regime that persuades people to save the minimum to take them off the state’s dependency list, and as gradually as possible to minimise the impact to tax revenues and the economy. ((This sounds like 15% auto-enrolment to me ))

The newspaper, like me, thinks that a move to TEE would be daft, for four reasons:

- It can’t be implemented retrospectively since there is £2 trn in the existing EET system.

- This means the two systems would have to run in parallel, increasing cost and complexity.

- It would reduce the incentive to save since it requires workers to trust that the government will let them have their pensions tax-free.

- This is a hard sell against the backdrop of constantly changing rules over the last 20 years.

- Tax-free withdrawals encourage early spending and pot-emptying, as per the Australian experience.

- The shift from EET to TEE would produce a one-time tax windfall that is in fact the bringing forward of tax revenues from the future.

- There could be trouble ahead, given the ageing population.

The Economist thinks that whole thing may be a red herring, designed to make a flat rate of tax relief (30%?) seem more palatable in comparison to a TEE system.

Let’s hope so.

Michael Johnson of the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) – whose paper Auto-Protection at 55 we looked at in March 2015 ((Spoiler alert – we didn’t like it )) – has published his own plan of how the government should reform pensions tax relief.

I’ve changed the numbering of his points to make things clearer:

- Pensions tax relief should be replaced with an ISA top-up (50%) on the first £8K of contributions each year.

- All employee contributions go into a Lifetime ISA under the same incentive, access and taxation rules.

- The Lifetime Allowance should be scrapped.

- Withdrawals before 60 would require repayment of the incentive and savings made after age 50 must remain in the ISA for ten years.

- Tax-free withdrawals after 60 would be possible subject to Treasury cost-modelling.

- Auto-enrolment contributions should be increased to 16.5% (6% employee + 5% employer + 5.5% in top-up) to target a two-thirds replacement rate for median earners.

- Employer auto-enrolment contributions go into a Workplace ISA sharing the annual incentive allowance with the Lifetime ISA.

- The Workplace ISA is locked until age 60.

- A Workplace ISA pension (annuity with 25% uplift) should be considered, available from age 60.

- These changes should be implemented via a “Big Bang” single date approach.

I’m going to make the assumption that existing ISAs live on outside this regime. In the worst case, that the £7K of ISA allowance not used up by the incentivised pension contribution is still available.

- It’s likely that Michael’s system could work – £19K of contributions (including the £4K government top-up) each year should be enough to keep people off state support in retirement.

- I think that the retirement tax rate would have to be zero for this system to work.

- I like the idea that annuities could be enhanced to encourage their take-up, though I’m not sure that a 25% uplift would convince me at age 60.

Overall though, it’s not a pension regime I would like to live under, or would wish upon those younger than me.

Investment Association boss ousted

Judith Evans reported on the backlash over the ousting of Daniel Godfrey, the head of the Investment Association (IA) – the asset managers’ organisation.

It’s thought that he was given the push because he was promoting consumer-friendly initiatives such as disclosing charges, and a “statement of principles” in which asset managers promised to put clients’ interests first.

He resigned after threats by Schroders and M&G to quit the group. Only 25 of 200 groups – representing a third of the £5.5trn in assets under management – had signed up to the statement of principles.

Insiders suggested that the IA had been acting more like a regulator than a trade body, and that Godfrey’s changes were not in the interests of members.

Claer Barrett agreed that Godfrey had been hounded out for his transparency crusade. She also thought it was a PR disaster.

(She also warned about the disruptive power of fintech and the threat to banks profits, but I’m less convinced of this – successful fintech groups are just as likely to be taken over by the incumbents.)

Claer thinks that the 25 groups that signed up the statement of principles (the list includes Legal & General, Axa and Newton) should leak the list of signees for a free marketing boost.

Neil Collins concurred with his two FT colleagues. He wondered just whose financial goals the IA was focussing on. Perhaps Richard Woolnough at M&G, paid £15m last year, or Martin Gilbert at Aberdeen Asset Management, paid £4.7m.

Pay packages like these make it difficult for fund managers to attack excessive corporate salaries.

Godfrey’s job was to encourage saving (through his members’ funds), to lobby for tax breaks andto moan about compliance costs. That’s what we can expect from his successor.

Corporate taxation

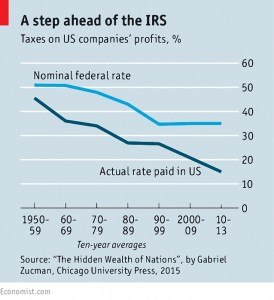

The Economist took another look at the taxation of multinationals.

The existing network of treaties was designed for the manufacturing age. Intellectual property (IP) licences are much easier to shuffle into low-tax countries.

The OECD calculates the savings / losses at $240 bn a year, or 10% of global corporate tax receipts.

America has a big problem – its 500 largest firms hold more than $2 trn in profits offshore, to avoid tax on repatriation.

Governments want to change things, partly because people are fed up with the avoidance (see below) and partly because they need the money.

We’ve mentioned the “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting” (BEPS) proposals before, but they were finally released last week. They will be submitted for approval by the G20 in November and aim to “put an end to double non-taxation”.

But the newspaper is disappointed in what has been achieved.

- There will be more country-by-country reporting of revenues, assets, employees and profits, though only to the authorities (not to the public).

- “Comfort letters” to corporations from friendly regimes will be passed to other jurisdictions.

- Some companies are preemptively paying more tax.

- And low tax countries are dismantling the worst structures (eg. the “Double Irish”).

But nothing has been done about the taxation of cross-border online sales, or on controlled foreign corporations (subsidiaries used mostly by use firms to park profits offshore).

Nor have interest deductibility (excessive deductions on debts owed to other corporate subsidiaries) or hybrid instruments (treated as debt in one country and equity in another) been fixed.

The biggest miss has been not dealing with the “independent entity” principle that allows parent and subsidiary companies to pretend that they are dealing with each other “at arm’s length”.

“Transfer pricing” rules are supposed to counter this but it’s often difficult to know if payments have been set at fair prices.

The newspaper recommends a top-down approach: treat companies as single entities, and apportion the tax take between countries using formula based on sales, assets, employees, profits etc.

What should matter most is where the purchaser of a product is based.

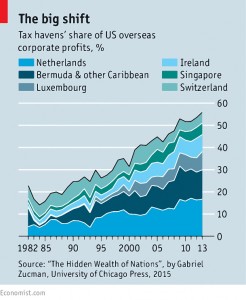

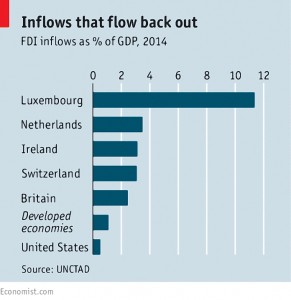

In another article, the Economist looked at whether European corporate tax havens are really reforming.

The Netherlands, Ireland and Luxembourg attract a huge amount of foreign direct investment, but much of it flows straight back out again – it’s all a tax dodge.

All three countries are promising reforms, but the newspaper thinks they are just tinkering.

Nor is Britain exempt from criticism. It’s easy for British-registered businesses to park profits offshore. Tax breaks on patent income are extremely generous, and Britain has more tax treaties than the three prime offenders.

The theory is that fake subsidiaries will evolve in to real ones, with real jobs. But the paper is not convinced.

Still on corporate taxation, a row blew up this week about Facebook’s profits in the UK.

It emerged that the social network giant paid only £4,327 in corporation tax in 2014. The company filed a £28.5M pre-tax loss which included £35.4m in share bonuses for its 362 UK staff (£96K per person).

The average UK salary is £26.5K, which attracts £5,393 in income tax and NICs. So there’s been a bit of an outctry.

There’s obviously a problem here, but it’s not the one that most of the media coverage suggested.

All corporations deduct staff costs from their profits. The more money their staff get, the lower the profits.

But the people who should be complaining about high salaries and bonuses are Facebook shareholders – ironically, many of them employees – rather than UK taxpayers.

High wages mean lower shareholder returns (through dividends, or gains in the share price). But money paid out to UK employees will be taxed eventually (through income tax, NI, capital gains or VAT).

The real problem is profit shifting of money made in the UK to lower-tax jurisdictions. That isn’t affected by UK salaries and bonuses.

Globally, Facebook made $2.9bn in 2014. The UK needs to be able to tax its fair share of that.

George Osborne plans to introduce a diverted profits tax on companies that move their profits overseas. Let’s hope that happens sooner rather than later.

Naomi Rovnick and Judith Evans looked at the government’s plans to float the rest of Lloyds bank for £2bn in spring 2016.

Lloyds already has about 2.8m private investors, but the offer includes a 5 per cent discount to the market price to attract more. Those who hold on to shares for more than a year will get another 10% (capped at £200).

The offer will prioritise those buying less than £1K, so incentives are likely to amount to no more than £150 per person.

Despite this, hundreds of thousands have registered their interest, many more than signed up for the Royal Mail float in 2013.

Apart from the incentives, the dividend potential is the main attraction.

- Lloyds used to be one of the biggest dividend payers in the FTSE 100.

- Payouts resumed this year and a 3.5% yield is expected for 2015, worth perhaps 5% in 2016.

The downside is that the shares are not cheap, and the sale comes amidst what could be the tail end of a property boom.

- Lloyds is valued at 1.3 times book value, whereas Barclays, HSBC, RBS and Standard Chartered all trade below book value.

- Lloyds’ biggest area of lending is mortgages, so it is heavily exposed to the UK property market, and rising interest rates.

Chinese AIM companies

Kate Burgess looked at the future prospects for Chinese companies on AIM after a spate of recent failures.

China Rerun Chemical was the latest of a dozen Chinese groups whose shares have been suspended or ejected this year. Cairn Financial Advisers resigned as its nominated adviser (nomad) and the company now has a month to find a replacement or it will be delisted.

This follows Naibu Global, which was delisted after its UK based directors lost contact with Chinese executives. Then food business Sorbic International left Aim after Chinese executives took control of the corporate seals (chops) and cash.

Children’s clothier Camkids was suspended after its nomad and two directors quit over plans to pay distributors most of the company’s cash. China Chaintek’s nomad quit in September, followed by three directors. It’s deadline for a new nomad will have expired by now.

In all, 13 Chinese firms have left AIM since May 2014. Six lost their nomad, and two failed to produce accounts.

Eighty Chinese firms have joined AIM in the past decade, of which 45 are left. Most have market caps below £25M, and their shares are tightly held by management.

The LSE has told brokers that they need to review each company’s systems and processes to make sure they meet the standards for trading in London.

It remains to be seen if this will make any difference. In the meantime, the safest policy is to steer well clear.

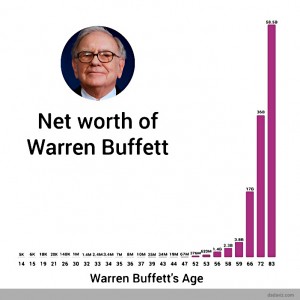

Warren Buffett the late developer

We end on a more optimistic note. Vintage Value Investing explained what a late developer Warren Buffett was.

Buffett was a millionaire before he was thirty, but it took him a long time to become the 3rd richest man in the world.

He didn’t become a billionaire until after he was 50, but even more surprisingly, 99% of his current $67bn wealth was earned after he was 50.

The graph below shows the beauty of long-term compounding.

So there is still hope for us all. I can’t expect to get to $67bn, but I’ll settle for 100 times what I have now!

I’m afraid that’s all I have time and space for today. I’ll try to squeeze a couple of the stories I haven’t got covered into next week’s Roundup.

Until next time.