Weekly Roundup, 1st September 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with their analysis of the recent market crash.

Contents

Great Fall of China

A team of five FT reporters looked at the implications for investors of “Grey Monday”, when the Shanghai Composite Index slumped after a surprise currency devaluation. This was followed on Tuesday by an interest rate cut.

The FTSE 100, S&P 500 and FTSE Eurofirst 300 all briefly went into correction territory (down more than 10%), whilst Germany and emerging markets went into bear territory (down more than 20%).

Commodities and emerging market currencies also fell steeply. The VIX index (the “fear index”) jumped to its highest level since 2011. Automated trading sent many ETFs far below the value of their underlying baskets of stocks.

The FTSE 100 was hit harder than most stock indices because it’s full of mining and commodities stocks (including oils) and its firms have large overseas sales.

Burberry is a good example, down 28% since February. The long-term growth story remains intact, and for those who believe this could be a good entry point.

Active managers did well, with almost 70% of UK equity funds performing better than the FTSE.

According to an FT survey of 8,000 private investors, 78% neither bought nor sold on Monday.

Bond yields also fell, with 10-yr gilts moving to 1.7% (though the have since recovered to 1.9%). Emerging market bonds are down 12% in 2015.

By the end of the week, many stock markets had recovered on the back of good economic data from the US (though Shanghai remained 8% down).

The basic message to investors was:

- don’t panic

- think long-term

- make changes gradually

- diversify

Apart from the last point being somewhat “stable-door”, it’s decent if obvious advice.

HL had tips for those already in drawdown:

- keep one year’s spending in cash ((I would recommend more than one ))

- stick to the natural yield in a downturn (don’t eat into underlying capital)

- make sure you are diversified

Looking forward:

- equities, especially “bond proxies”, look overpriced

- Europe is the best value

- commodities are cheap for a reason (declining Chinese demand)

- emerging markets are vulnerable to a Chinese hard landing

The big question remains whether the US can risk raising interest rates in September. Falling commodities prices mean that significant inflation remains unlikely. The Chinese devaluation only exacerbates things.

Last week it looked like the Fed would not raise rates, but the noises coming out of Jackson Hole over the weekend suggest that a rise might still be on the cards.

If a jobs report on September 4th shows strong employment growth, rates could go up despite market volatility.

The Economist had two articles on the same subject. Rather than focus on western interest rates, the newspaper looked at the implications of a possible Chinese slowdown for emerging markets and first world markets.

Fears for China itself – and the potential impact – maybe overdone:

- The equity market in China is small – market cap is only a third of GDP, compared with more than 100% in developed countries.

- The near tripling of prices in the year to June was no more reflective of the economy’s prospects than the subsequent collapse.

- Less than a fifth of household wealth is in shares, and the leverage financing their purchase is only 1% of banking system assets.

- Property is more important, responsible for 25% of GDP. In the past few months prices and transactions have both been healthier than previously, reducing fears of a property crash.

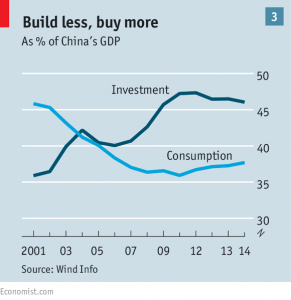

- Exports are down, but China is switching from an export / command economy to a consumer / market economy, and services, incomes and consumption appear resilient.

- Services are now a bigger share of output than industry.

- The central bank also has plenty of room to loosen policy.

- Even after this week’s cut, the one year rate is 4.6%, and bank reserve ratios are 18%.

- Growth rates have fallen but because the Chinese economy has grown, even 5% growth this year will mean more to world GDP than the 14% growth of 2007.

But western confidence in the Chinese government has been damaged by this week’s market interventions.

The “devaluation” may just have been a technical change to the way the yuan exchange rate is managed. But it came across as the start of a currency war.

And worse, the Chinese government’s confidence in free markets may also be damaged:

- it may not expose state-owned firms to full competition

- it may not risk capital flight from a floating (weakening) yuan

The second fear is a re-run of 1998’s Asian crisis. The main reason for this is capital flight as the US prepares to raise rates.

But more Asian currencies float freely now, and most countries have large FX reserves and current account surpluses. They have fewer foreign creditors.

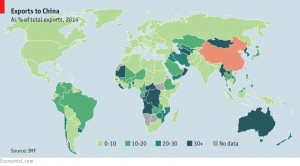

But commodity exporters like Brazil, Indonesia and Zambia are in trouble. China consumes about half the world’s aluminium, nickel and steel, and nearly a third of its cotton and rice.

Sliding emerging currencies will hurt countries with local currency revenues and dollar debt. The dollar is up 17% against the currencies of its trading partners in the past two years. Brazil’s real is down by more than a third.

Even worse, emerging market growth was already slowing, as Brasil, Russia and India failed to implement reforms to improve productivity.

The West has less to fear. US exports to China were less than 1% of GDP in 2014.

But Germany is more exposed, and the S&P 500 had 48% of sales outside the US. Falling currencies will hit these exports.

The newspaper is against a US rate rise in September, and thinks that Europe and Japan should loosen policy further to stimulate demand.

Looking further ahead, the challenge is to improve productivity, so that western GDP growth can take over from fading Chinese expansion.

Low interest rates are the problem

Back in the FT, Merryn wrote about the problems with low interest rates.

In the UK the bank rate has now been 0.5% – its lowest for at least 300 years – since 2009, and could stay like that for some while longer.

The general worry is that if rates are raised too soon, the recovery could all go horribly wrong. Merryn thinks that cause and effect may be the other way around – low rates are holding back the economy.

The basic problem is capital misallocation:

- low interest rates encourage borrowing to invest in things that might not look such a good bet under higher rates

- risky and yield-producing assets like shares (and in the UK, houses – particularly buy-to-let) seem more attractive

- buying back their own shares becomes attractive to companies – there’s been a lot of this in the US

Global corporate debt has risen from 26% to 56% since the crisis. This borrowing has had several effects:

- since it creates excess supply (eg. in the oil industry) which in turn leads to lower prices (eg. oil) it can be deflationary

- the borrowing (and QE again) push up asset prices

- shares generally and US shares in particular have been driven up to the point where they look expensive relative to earnings

- UK house prices are also high

- this “non-productive” debt diverts funds from R&D and productivity-enhancing investment

- it will also need to be paid back at some point, increasing a company’s risk level in the future

Low interest rates also affect the actuarial calculations behind company pension schemes, creating and inflating deficits.

- this again diverts cash from productive uses like R&D and investment towards productivity

- UK companies have paid £500bn into their pension schemes over the past 15 years but the total deficit has risen from £250bn to £900bn.

Flop pickers

Tim Harford wrote about flop pickers – people who can be relied upon to identify a bad idea in advance.

Fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies have long used focus groups to identify which new product ideas might be successful. But still many products fail.

Since the 1980s, companies have searched for “lead” customers – those with more advanced or specialised needs who might predict where the market is heading.

But if savvy influential consumers can predict a product’s success, might there not also be consumers whose support spells death for a product?

The key is to demonstrate that such a customer likes not just one particular flop, but all flops.

Management professors Eric Anderson, Song Lin, Duncan Simester and Catherine Tucker have found such people, who they call “Harbingers of Failure“.

They used data on 100,000 customers from a chain of 100 convenience stores, over 10 million transactions and 10,000 new products. The 40% of products no longer stocked after three years were deemed flops.

Harbingers bought lots of flops and kept coming back for more of the same flop.

It’s an interesting finding, as it’s not clear why someone who likes an unpopular soft drink would also love an unpopular shampoo.

It’s also interesting that the harbingers couldn’t be identified by demographics. They look like us, and they live among us. They just like the stuff we hate.

This is an idea that could be extended to stock markets, as a kind of social trading extension of the “stock tips from the elevator operator” sell signal.

If only we could persuade the brokers and the spread-betting firms to release information on what their least successful clients were up to, then we could do just the opposite.

Charging for public services

The Economist had a couple of articles about pay-as-you-go government.

As Western economies try to balance their books without raising taxes that have to be publicly flagged in finance bills, they are instead charging higher fees for services.

These can be aimed at groups that are not politically organised (for example, those going through divorce) so as to not raise opposition.

Recent examples include:

- US cities have increased residential charges by 25% over the past 15 years.

- Half the EU countries have increased healthcare charges since 2008.

- Britain is introducing new fees across the board, from the courts to municipal pest control.

- Petty offenders sometimes pay more in fees (over which judges have no control) than they do in fines.

- The new “criminal courts surcharge” is expected to raise £85m a year.

- Employment tribunals have seen a large fall in sex discrimination claims since fees were introduced, with no surge in the success rate.

Charging for services helps allocate resources efficiently and fairly, deterring overconsumption. Metering water and university tuition fees are good examples.

But that doesn’t make them popular (think parking meters).

And when politicians increase charges to more than the cost of service provision, they can be regressive, and are really taxes in disguise.

Global company tax rules

The Economist also looked at proposals for consistent global rules on company tax.

The OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project aims to bind multinationals to a single set of rules with no loopholes.

Sceptics worry that it could lead to chaos if countries adopt the new guidelines to differing degrees, or conversely, if some governments

take additional action to prevent tax revenue being siphoned abroad.

With two months to go before the presentation of the plan to the G20, the main concern – expressed most recently by the US Treasury – is that Britain and Australia are “going their own way”.

Britain’s new “diverted profits” tax imposes a levy on profits routed to tax havens through “contrived arrangements”.

Multinationals worry about the possible return of double taxation, but there seems no sign of this at present.

Most of the BEPS work is on “intangibles” – brands, copyrights, patents etc. Much profit shifting (and many tax breaks) relate to intellectual property (IP) and its royalties.

The tax breaks won’t disappear, but BEPS should regularise and dilute them. In practice this means that countries currently without them may have to give them a try,

A popular scheme is the “patent box”, where companies pay less tax rate on profits from IP developed in a particular the country.

Britain’s patent box cuts the tax rate in half, to 10%; the US is proposing the same. Ireland plans to match the Netherlands at 5%.

Germany argues that no additional innovation is encouraged, and R&D spending is merely shifted to the lowest tax jurisdiction.

As a compromise, Britain has proposed a “modified nexus” approach which links tax benefits to the location of economic activity as well as the patent development. But companies will pay less tax on IP they have bought, or whose development they outsourced.

Tracking of R&D spending by the countries offering the breaks means there will probably be sweetheart deals with favoured industries.

Corbynomics

The Economist also looked at the idea that Jeremy Corbyn’s economic policies – Corbynomics – enjoy widespread support from economists.

I’m not suggesting for a moment that Corbyn can ever be elected into government, but perhaps a closer look will tell us something about economists.

Let’s start with the policies. Corbyn wants to introduce a “maximum wage”, nationalise energy companies and apparently reopen coal mines.

Other ideas include tax reform to raise many billions seemingly wasted at the moment, and “People’s QE” – printing money to boost investment.

Readers old enough to remember the turmoil of the 1970s may find many of these ideas strangely familiar.

Despite these throwbacks, he managed to come up with a letter from “leading economists” backing his anti-austerity position.

I struggle to call the gradual reduction of the budget deficit over ten years austerity, and conditions in the UK remain substantially better than those of my childhood, but that’s the label that has stuck.

It’s certainly a plausible position that current policies are holding back growth (see Merryn above).

Boosting Britain’s low level of investment – as far as it is sensibly possible – is also a good idea. The question is how far, and using what measures.

Corbyn wants a “national investment bank” to spend on roads, houses and green energy.

Funding comes from removing £93 bn a year of “corporate subsidy” and £120 bn a year of tax currently evaded and avoided. That’s a lot of money.

Unfortunately, that money doesn’t exist. The £93 bn comes from a paper which counts state spending on education and health as corporate welfare.

And there is evidence from HMRC that R&D tax credits produce £1.53 to £2.35 of investment for each £1 of relief.

The £120 bn number comes from a pressure group called Tax Research, and is four times the government estimate. No details are provided to close the gap.

People’s QE would mean the creation of money to buy bonds from the “National Investment Bank”, rather than government bonds as at present. Assuming that these bonds can be written off to avoid the national debt increasing, then this is just more QE with a new name.

The government currently hopes to get away without more QE, but there would be more if needed. So the issue becomes one of expectations.

If People’s QE worked – which it might well in the short term – then PM Corbyn would presumably ask for more. And the credibility of the BoE would be shot, and interest rates would rise.

Which would be the end of increased investment.

Market cycles

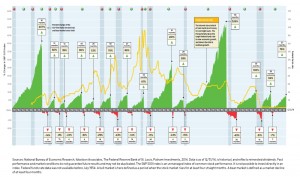

We end this week with a diagram I came across on Twitter. It shows the bull and bear markets in the S&P 500 index dating back to 1949.

After the way the markets behaved last week and again today, it’s reassuring to see how little red – and how much green – there is in that chart.

Until next time.