Weekly Roundup, 20th October 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story.

Contents

UK mining stocks

Naomi Rovnick looked at whether UK mining stocks have reached a turning point. ((I should warn you going in that this week’s article is awash with graphs. It’s not actually the regular column from the print edition of the FT, since I couldn’t find that online. Instead it’s a different version of the article by the same author from the same week ))

The fall is prices has been driven by the China slowdown, since the world’s second-largest economy had been the main consumer of most commodities.

There’s also an over-supply problem, for example in iron ore:

Together, these two factors have not surprisingly driven down prices:

To fund production growth, miners borrowed. Low prices mean that these debts are now harder to service, so companies like Glencore are selling assets to improve their balance sheet.

So is this the bottom? One positive is that the anticipated Fed interest rate hike seems to be disappearing over the horizon:

Another plus is the high dividend yield that the sector now offers:

But the dividend cover is only 1.1 times, which means that dividend cuts are likely.

And perhaps the Chinese economy has permanently changed. no longer a major commodity consumer, China is now exporting ever more steel:

High operational leverage and no pricing power is not a terribly attractive combination in a company. Miners are really a geared play on global economic growth, so the real question is will there be a lot of that around?

Buy to let

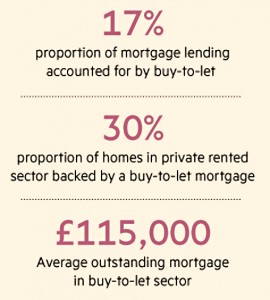

James Pickford looked at the impact of the new tax regime for buy-to-let (B2L). ((I must make a tiny disclosure here – I own a 50% share in my late father’s house in Manchester. This is rented out to a housing association and after deducting the renovation loan repayments, brings me in less than £20 a month. I am not a massive fan of B2L ))

At the moment B2L landlords can deduct mortgage interest from their rental income before paying tax – this is in fact the standard deduction available to all businesses. This means they save tax at their marginal rate.

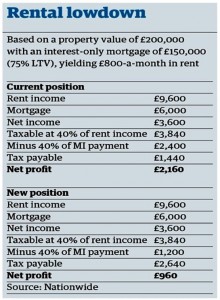

From 2017 to 2020, this will be gradually restricted to 20% relief. The graphic below (from the Guardian in July, when the changes were introduced) explains the implications.

In addition the 10% annual “wear and tear” allowance is being withdrawn in favour of receipts from actual repairs.

The exact consequences depend on the investors tax-rate, mortgage interest, gross rental yield and leverage, but at the margins there are likely to be some who need or want to rationalise their portfolios, and others who no longer wish to expand.

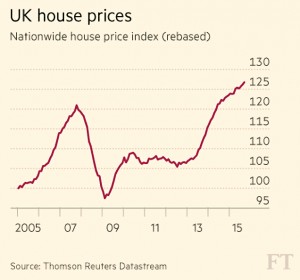

This in turn might put downward pressure on house prices, which have recovered well from the financial crisis. The average first-time buyer price is now £215K.

It’s possible of course that landlords will simply raise rents, though it remains to be seen if this will be possible.

It’s also the case that two-thirds of landlords own their properties outright, and so will not be affected – they are already not deducting any mortgage interest.

Houses within a company structure are also not affected, though stamp duty costs can be high under this arrangement, especially near London.

There also those who think that any departing private investors will simply be replaced by professional and even institutional buyers.

At this stage, it’s difficult to draw any real conclusions for the housing market as a whole, though B2L looks as though it will become less profitable.

Down in the South it’s already highly dependent on further rises in house prices, and it looks like this will become the case to an even greater degree. Fifteen years ago was the time to get involved in B2L.

P2P ISAs and SIPPs

Lots of acronyms here. Judith Evans reported on a warning from city veteran John Spiers – founder of BestInvest – that it’s a mistake to allow P2P lending into the ISA system.

His key worry is that P2P hasn’t been tested through a full market cycle, which I take to mean a credit / interest rate cycle. Zopa was around through the 2008 crash and suffered very little, with defaults of only 5%. ((I pulled most of my money out, expecting a train wreck ))

But the P2P market was much smaller then, and arguably the quality of borrowers was higher. £1 bn of new loans were made during the first half of 2015.

Spiers is also concerned about a lack of liquidity. P2P platforms do offer secondary markets for loans, but they are limited in scope and don’t guarantee immediate trades.

He also worries about the incentive for P2P platforms to grade loans as higher quality than they really are, to grow their loan book rapidly in the face of competition from new entrants.

I share most of his concerns, but would be happy to hold a proportion of my ISA savings in P2P, and I’m looking forward to the tax wrapper boosting the somewhat disappointing returns from the sector.

The real danger is to those ISA investors who only ever take out a Cash ISA. They are already condemning themselves to poor long-term returns.

If they now swap out a major portion of these Cash ISAs for Innovative Finance (IF) ISAs, they will be adding counterparty and interest-rate risks to their problems.

The new IF ISA will launch in April 2016.

Of more immediate concern is the P2P SIPP that has just been launched by Abundance. Apparently RateSetter and ThinCats already provide access to their P2P products via SIPPs, so this is a growing trend.

I had planned to write something along the lines of “What next? A Crowdfunding SIPP?” but in fact, that’s almost what the Abundance product is.

Abundance don’t make loans to individuals, in the way that Zopa do. Instead they lend to mostly ethical infrastructure projects like renewable energy – a sector that is not spectacularly viable without the government subsidies that have just been cut / removed.

So not crowdfunding, since it’s still debt rather than equity, but some of the riskiest debt you could find.

This is clearly targeted at investors with a conscience who are scared of stocks, but the same dangers apply as with the P2P ISA, except more so.

Debt products don’t normally return enough to form the bedrock of a pension you will invest in and draw from over a period of 30 to 50 years.

The Abundance projects typically return 6% to 9% pa, which is more like it, but this reflects the riskiness of the underlying businesses. The product wouldn’t sound so attractive if it were renamed a “junk-bond pension”.

Charges are 0.3% pa, with a minimum of £100. That’s comparable to regular SIPPs – from providers like Fidelity and AJ Bell YouInvest – that allow you to build up a diversified portfolio of index trackers or ETFs.

At the moment there is only one project open – a solar panel scheme returning 7% pa.

Anybody who is tempted by the Abundance product should make sure that it forms only a small proportion of their net worth.

When to transfer your pension

Alan Higham, who has started a consumer website called PensionsChamp, had a useful article in the FT about when – if ever – to transfer your pension.

This advice is aimed at frustrated DB pension scheme members who are typically unable to access their pensions at age 55, under the new pension freedoms that apply to members of DC schemes.

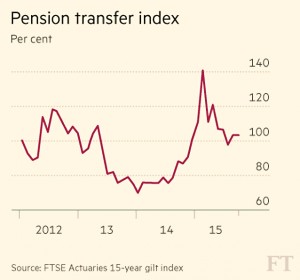

It’s important to remember that pension transfer values are linked by actuarial calculations to the bond markets – in the UK, to the price of Gilts.

So some times are more favourable for a transfer than others. Alan is an actuary, and provided a graph covering the last four years.

After a spike in values at the end of 2014, we’re now back where we started at the beginning of 2012.

Another point to consider is tax. DB pensions are valued at 20 times the income they produce. This is actually a favourable treatment in comparison to DC pensions, as we shall see.

So a DB pension of £50K counts as a £1M pot, which is the new lifetime allowance for a tax-free pension pot as of April 2016. ((By comparison, a DC pension pot of £1M could only sustain an annual income of between £35K and £40K ))

A transfer at the “wrong” time (when transfer values are high) could trigger a tax charge at 55% on the surplus. ((Though the pot left over would still be higher than that from a transfer when values are low ))

In fact, it isn’t in general a good idea to transfer, as DB pensions often come with bells and whistles that are lacking in DC schemes.

And the actuaries will at best give you a 50/50 chance of breaking even on your transfer, despite you taking on the risk of getting there. Transfer values are always a lot lower than the pot needed to buy an annuity of the same amount.

Alan came up with six reasons to transfer. Four relate to having immediate needs for capital:

- you are ill and have a reduced life expectancy

- you have debts with high interest rates

- you already have more than enough secure income for life

- the company supporting the scheme is in trouble and you want to get your cash out before it crashes

The other two relate to not making use of the bells and whistles:

- you are single and can’t make use of the surviving spouse’s pension

- you have a same-sex partner who isn’t eligible for the spouse’s pension

Under current legislation, transfers above £30K need to be advised, so that will cost you at least a few hundred pounds, though Alan says that 3% charges are common. That’s £1,500 on a £50K transfer, or £30K on £1M.

- There is a directory of firms that provide advice on transfers at the Money Advice Service

If your company scheme does go bust, the Pension Protection Fund (PFF) will underwrite 90% of your pension if you are under normal retirement age, or 100% if you are over.

- There’s also an age related cap on your payout: £36.4K at age 65 (£32.8K if you are on the 90% rate).

- And the PPF can reduce rates in the future if it is running out of money itself.

Divorce

Diane Coyle looked at the implications of a Supreme Court ruling that divorce settlements can be re-opened if it is found that one of the spouses lied during the original proceedings.

Diane is an economist, and quotes the late Nobel Prize winner Gary Becker’s paper A Theory of Marriage. Apparently marriage is a “means of household co-production with a specialised division of labour”. ((I’ll resist the strong temptation to insert a joke at this point ))

Nowadays there is more assortive mating. Women earn more and tend to marry similar people. The old division of labour is less worthwhile when both partners have the same earning power.

Where the partners are less equal ((As in the cases to which this week’s ruling applied )) Diane’s take is that there needs to be an incentive to stop husbands lying to get away with more money. She doesn’t mention whether we should stop wives lying.

Divorce remains a Bad Thing economically, as both sides end up with a lower standard of living.

This is not just from paying the lawyers. Splitting duties allows each partner to focus on what they are best at. Tasks for two people batched together to be performed by one are more efficient. And there are standard economies of scale (household bills).

I think she is trying to argue that the poorer half of the union contributes equally to the greater wealth and deserves an equal share of it. I disagree, but as long as the rules are clear, things are not so bad.

Anyone who doesn’t like the current divorce rules ((Any mentally competent man, in my eyes )) shouldn’t sign up to them by getting married. But marriages can last a long time – years in some cases – and it seems a bit much to move the goalposts halfway through the game.

Diane anticipates that the rich will soon substitute capital for labour in “the domestic production function.” They are going to buy robots.

She doesn’t mention how this should affect divorce settlements where the stay at home spouse then actually contributes nothing (in economic terms, of course). ((Which is already the case for the rich, who use servants instead of robots ))

Deaton’s Nobel Prize

From one Nobel Prize winner to another. Angus Deaton has won the Nobel for Economics “for his analysis of consumption, poverty, and welfare”. ((Not him, the other Angus Deaton ))

The 69-year-old Scottish Princeton professor has been working on inequality since before it became fashionable. He sees it as a product of success – it’s the haves that make the have-nots so visible.

His studies include:

- how much more the poor eat when they get more income

- how well insured they are, and

- the relationship between health and income growth.

But his most famous finding is that money does buy happiness, up to about $75K / £50K per year.

- Below that, people feel more unhappy the less they have.

- Above that, then don’t get any happier.

He also worked on the way economists estimate demand. Along with John Muellbauer, he proposed the “Almost Ideal Demand” (AID) System.

- Earlier models assumed demand increased with income

- AID suggested that a 1% pay boost might “raise porridge demand by 2% for a pauper, but only 0.1% for a prince”

He also worked on the relationship between consumption and income. The difference between the two is the savings rate, which can determine society’s future wealth.

The problem was to explain why consumption appears less volatile than income. Milton Friedman suggested that people smooth consumption as their income varies ((I know I do, but perhaps I am atypical ))

Deaton pointed out that where a pay rise acts as a signal that there are more to come, people should spend some of the money from the future, making consumption more volatile than income. The fact that it isn’t is known as the Deaton paradox.

Merger abritrage

Neil Collins looked at the value gaps in the Shell / BG and AB InBev / SABMiller mergers.

- The former offers £12 for £10.80

- The latter offers 44 for £39.55

Both deals are agreed, so it should just be a matter of buying the shares in the target companies and waiting. With interest rates close to zero, the waiting is almost free.

But competition authorities everywhere will negotiate promises of good behaviour from the proposed brewing giant at least. SAB may face a year in purgatory, and bits being carved off.

Shell’s takeover of BG has lower regulatory hurdles, but the value gap persists.

The failure of the earlier bid by Pfizer’s for AstraZeneca may be to blame. The depression covering the whole sector as we ponder the potential end of the oil age may also be a factor.

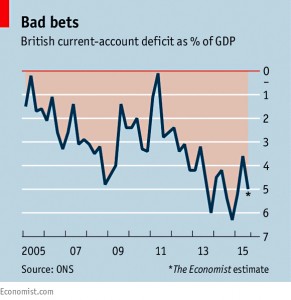

The current account deficit

The Economist looked at Britain’s current account deficit. The government brags about cutting the budget deficit from 10% of GDP in 2010 to 5% now.

But over the same period the current account deficit (CAD) has got bigger. It’s now the largest as a percentage of GDP of any developed country, and the second biggest in absolute terms (behind the US).

The CAD was big news in the 1960s but barely features nowadays. Should it?

The CAD is made up of three smaller (negative) numbers:

- exports minus imports

- British investors’ foreign earnings minus foreign investors’ earnings in Britain

- money transfers into Britain minus remittances home from foreign workers in the UK

The biggest of the three is the excess of imports over exports.

But the recent deterioration is due to reduced income from foreign investments in slow-growing places like Europe (rather than China and India), whereas foreigners’ investments in Britain are doing very nicely nowadays.

To finance the CAD Britain sells assets “from chocolate factories to posh London homes” and borrows more money.

But a large CAD is not as dangerous as it used to be. There is no currency peg to defend, and the pound will fall to correct a CAD which is too big for too long.

This will create inflation and freeze incomes, but things will recover.

There should be no capital flight either. Recent liabilities are mostly equity and longterm debt, which are “stickier” than deposits or short-term debt.

And Britain is attractive to foreigners – few fast-growing economies have similar property rights and governance. Brexit is the major risk here.

Until next time.

The CAD is interesting, especially in light of the labour government’s changes to move away from US$ for the € instead… But it’s not that big of a deal, it fluctuates wildly over the years. Until we start producing more stuff in Britain I guess it will still be fluctuating under that line for years to come…

You’re right – it’s either export more or let the pound devalue.

But it doesn’t help that we are so tied to the most moribund economic area in the world (the Eurozone).