Weekly Roundup, 25th October 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with a feature on how to prepare for the inflation that is heading the UK’s way.

Contents

Inflation

Inflation hit 1% pa in September.

- This is still low historically, but it led to a rash of headlines that were variations on the theme of it being the highest rate we’ve seen for two years.

- Then we had the Marmite wars as Tesco resisted Unilever’s attempts to hike the price of a yeast spread.

To be fair, the post-Brexit crash in Sterling means that imports (with a bit of help from gently rising oil prices) should drive inflation above the Bank of England’s 2% pa target within the year.

- It could possibly go significantly higher, with some economists forecasting 4% pa in 2018.

So what will change, and what should you do about it?

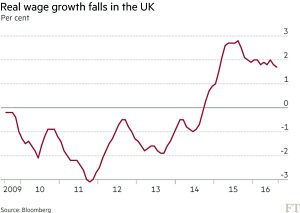

For consumers, inflation is bad, as it means prices are higher.

- So workers will naturally seek wage increases that at least match inflation.

- These may or may not be forthcoming, depending on the state of the economy and the employment market, but the odds must be against it.

- Unemployment is likely to rise during the Brexit process, which will weaken workers’ bargaining positions.

The effects of the planned increases in the Living Wage are also difficult to predict.

- On the one hand, a lot of low-paid workers will get pay rises of more than the inflation rate

- On the other hand, the higher wages could make a lot of entry-level jobs non-viable.

For (cash) savers, inflation could look like good news, as it might mean that interest rates finally begin their climb back to normality.

- But interest rates are unlikely to rise as quickly as inflation.

- The real (post-inflation) base rate is already at minus 0.75%, and that gap probably won’t close over the next 12 months.

- Despite this, many people will probably look to remortgage in order to lock in current low rates.

Bank of England governor Mark Carney has already said that he would be “willing to tolerate a bit of an overshoot” for a few years (though the current BoE forecast has a peak of only 2.4% pa in 2018).

- Janet Yellen has said the same thing.

- This is no surprise, since central banks have been trying for years to create inflation in order to shrink the 2008 crisis debt pile.

In the short-term, the most likely impact is that the predicted UK November rate cut from 0.25% to 0.1% or even zero will be shelved.

- So cash will not be a good place to be during a period of inflation.

Retirees with annuities have similar problems.

- Most have level (rather than inflation-linked) annuities, and these will suffer if we have a few years of moderate inflation.

- In contrast, the State Pension is “triple-locked” to at least match inflation.

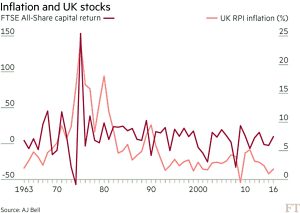

For investors, “real” and “asset-backed” investments (property, infrastructure, commodities, and even gold and SWAG in general) should fare best.

- Stocks normally do ok under moderate inflation, but any rise in interest rates could trigger a bond sell-off, with an equity pullback as collateral damage.

- Normally inflation-linked bonds (linkers) would be the obvious choice, but these are already expensive and will only work if inflation is higher than expected.

- Equity sectors tipped by analysts to do well are consumer staples (Unilever, Reckitt Benckiser) and Veblen (luxury) goods like Burberry.

- Infrastructure and healthcare companies are also a good bet.

Bond market

It was a thin week for the FT, so we’re off to the Economist now, with a look at the changing face of the bond market.

- The “vigilantes” of the 1990s have been replaced by forced buyers.

- The bond market remains a scary beast, but for the opposite reason to before.

It used to be difficult for a country to run a high debt-to-GDP ratio, as the vigilantes would sell off their holdings in bonds from “irresponsible” countries.

- But now everyone has higher ratios than back in the 1990s, and there has been no sell-off.

The reason is that many market participants now have no interest in maximising their returns.

- Central banks are the biggest culprits.

- The holdings of the six most active central banks (US, Japan, Europe, UK, Switzerland and China) have grown from $3 trn in 2002 to $18 trn now.

- The central banks want low bond yields (high prices).

Neither will liability-matching pension funds and insurance companies sell if yields fall.

- In fact they will buy more, since lower yields increase the present value of their future liabilities.

And commercial and investment banks are forced by regulation to hold government bonds as collateral and as a liquidity reserve.

So the price-discovery function of the bond market doesn’t work, and many bonds trade on negative yields.

- This makes it difficult to use bonds as part of a wealth preservation or investment strategy – under present conditions, how do you know when they are cheap or expensive?

Bonds are now just another form of cash – something that central banks will buy, that need not generate a significant return.

- “It’s about return of capital, not return on capital” said one economist.

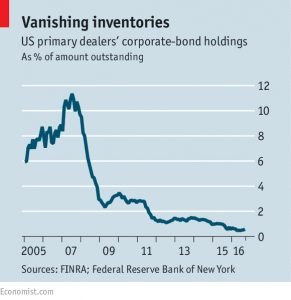

Alongside the lack of price discovery sits a lack of liquidity, particularly in corporate bonds.

- These rank lower than government bonds, and banks need to hold more capital to reflect the risks.

Bond-dealing bank inventories have fallen from 2% of the market in 2008 down to 0.2%.

- When the sell-off comes – perhaps triggered by a few Fed rate hikes after a Clinton win in the US presidential election, or perhaps by rising global inflation – price moves will be vicious.

While we’re on bonds, the letters section featured a few corrections to last week’s article on EM corporate bonds:

- recent inflows of $11.5 bn are “chump change” in a sector with $1.5 trn of bonds outstanding

- down-grades to Russian and Brazilian sovereign debt led to unjustified knock-on downgrades to corporate bonds from those countries, which skews the numbers on downgrades

- and the issuers are 40% banks, 33% commodities and 10% utilities, all sectors that wouldn’t suffer greatly from a drop in world trade.

Liquidity is the big problem, as with sovereign bonds.

US Election

In MoneyWeek, Dan Denning looked at how to position your portfolio for the US election.

- Dan is predicting a Clinton win, so a Trump victiory is the shock result that will spook the markets.

- The dollar will fall (though perhaps not against the Mexican peso).

But Clinton is also a protectionist, and will increase government spending.

- So the dollar should still fall, but more gently, over perhaps a year.

The flipside of a weaker dollar is a higher gold price.

In terms of sectors, defence and infrastructure should do well under either candidate.

- Clinton will be worse than Trump for pharma, biotech and energy (though perhaps better for solar energy).

Mutual funds

Back in the Economist, Buttonwood looked at a new book about mutual funds – Empire of the funds by WIlliam Birdthistle.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=B01GI5F0HI]

Birdthistle reveals that many funds have multiple classes of share, each paying a different level of fees.

- Unsurprisingly, small retail investors pay the most.

- He provides a table from Oppenheimer for a fund with six classes of share.

- Fees range from 1.01% pa to 2.2% pa.

Birdthistle also questions the idea that charges should be based on the size of the assets being managed.

- Funds don’t cost 20% more to run if the market goes up 20%.

- There are scale economies, and these are not being shared with investors.

Then there is the “distribution and service” fee, known as the 12b-1 in the US.

- This is used to market the fund to new investors, but is paid by existing investors, rather than the fund manager.

There is also a potential conflict of interest arising from the “soft dollar” compensation to funds from brokers – not just free research, but also phone and hotel bills.

- Birdthistle recommends that the percentage of independent trustees be raised from the current 40%.

Conflicts of interest are legion in investing.

- It’s one more reason why you do as much as you can for yourself.

- Nobody cares about your money as much as you do.

Of course, you can’t pick individual stocks around the globe to form a diversified portfolio, and will need to rely on funds to some extent.

- But you can use low-cost index-tracking ETFs for exposure to foreign developed markets.

- And listed investment trusts to gain access to less-liquid emerging economies.

Here in the UK, it’s reasonably safe to pick your own stocks.

Social mobility

The Economist also wrote about Theresa May adding herself to the list of new PMs who want to make Britain “a country that works for everyone” – or as John Major put it 25 years earlier, “a genuinely classless society”.

- Britain is not currently very socially mobile (of the big, rich countries, only the US is less so).

- And many people can remember the period between the 1950s and 1980s when it was much more so.

Unfortunately, this was down to a one-off increase in the number of well-paid white collar jobs, which is unlikely to be repeated.

- There’s no room at the top any more.

Which means that future social mobility must mean people moving down as well as up.

- And this is a harder to achieve.

The wealthy protect their young through inheritance, and funding education, both private schools at primary and secondary level (leading to massive over-representation at the best universities), and support for postgraduate study.

- 11% of the UK workforce now has postgraduate qualifications, up from 4% in 1996

- Rich kids can also afford to take the unpaid and informal internships that leads to jobs in many of the most popular industries and professions.

It’s hard to see a Conservative PM doing much to change this.

Public vs private companies

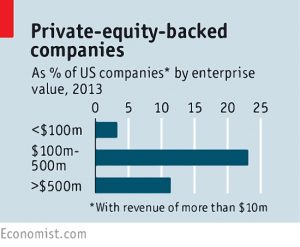

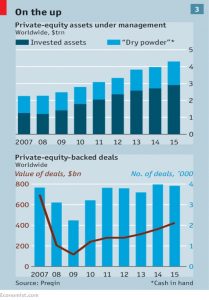

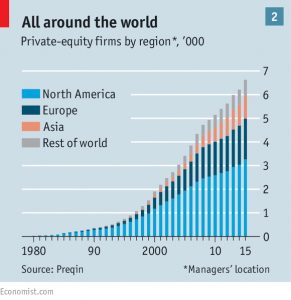

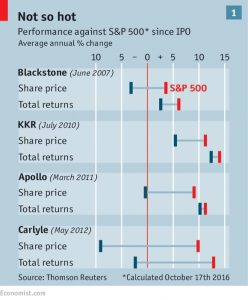

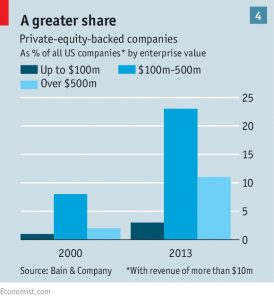

A leader in the Economist looked at the decline in public companies in the US.

- The number of listed companies has fallen from 7,000 in 1996 to 4,000 today.

- Firms with giant valuations like Uber and Airbnb have raised all their money through VC and then private equity (PE).

- The value of 2016 IPOs in the US is likely to be close to one quarter of that ten years ago.

And private equity firms are becoming the buyer of choice for more mature firms (as another article reports in more detail).

- There are now 6,628 PE firms, up from 24 in 1980.

- 620 new firms were founded in 2015.

- Carlyle is now America’s second biggest employer after Walmart, with 725,000 staff.

Not only do new tech startups need less capital that previous generations of firms, the red tape introduced since the 2008 financial crisis, and the negative aspects of being in the public eye mean that few founders want to set themselves up for explaining quarterly results to Wall Street.

A lot of this is understandable, but it’s not good for capitalism.

- Stock markets are liquid, transparent and relatively cheap for even the modestly well-off to access.

- Private equity is illiquid, opaque, more expensive and aimed at the rich.

When growth becomes concentrated in a few sectors (eg. tech) which are hard to access, this can be a real problem.

So governments need to remove any penalties for being public.

- The Economist wants to see the US’s “carried interest” tax-break for PE removed (both presidential candidates plan to do this).

- Phasing out the tax advantages of debt over equity would also help, as would bringing in annual reporting for unlisted companies (already present in the UK).

Prefabs

The Economist also reported on a new factory in Leeds owned by Legal and General’s housing arm.

- It will make “modular” houses – prefabs to you and me – and churn out 3,000 a year.

It sounds a lot, but the UK needs 250K new homes a year, and consistently builds less than 100K.

Pre-fabs are quicker to build than normal houses, needing 25% less labour and less of the sub-contracting that slows construction.

- The new modular houses are also said to be more energy efficient.

Pre-fabs have had a bad name in Britain because of the horrible stuff put up after World War 2, but L&G promises that this stuff is different.

All they have to do now is persuade people to live in them.

- And increase annual production by 5,000%.

Until next time.