Weekly Roundup, 2nd November 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with The Long View, which this week was about a coin-tossing game.

Coin toss

John Authers looked at a coin-tossing game organised by a couple of asset managers (you can play online here).

- The players were given $25 and 30 minutes to turn it into $250.

- In order to motivate them to play well, their final balance would be paid out in real money at the end of the session. (( Note that the online version is just for fun ))

The coin has a 60% chance of landing on heads, and you can bet any proportion of the money you have in front of you on each bet.

- But if you go down to zero, the game ends.

I’ve come across this game before, and the best strategy is something known as the Kelly criterion (identified in 1955).

- You bet a constant proportion of your money, calculated from how much the odds are in your favour.

- You double your percentage chance of winning, take away 1, and that’s your percentage bet.

So in this case, 2 * 60% = 120% – 1 = 20%, so we need to use 20% stakes.

- In effect you are betting the proportion by which your chances of winning exceed the random 50%.

This strategy can be adapted to card games such as blackjack, where your chances of winning on each hand wax and wane.

- You bet more when the odds are in your favour.

- Of course, you have to be pretty good at watching the cards go by to realise when the odds are in your favour.

So this game has quite a lot in common with investment.

- The stock market basically goes up over the long-term, but short-term returns (the next coin-toss) is / are unpredictable. (( As John explains, the stock market rises in line with economic growth ))

- This means that how people deal with the variable short-term returns should give us an insight into how they deal with stocks.

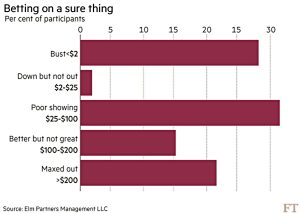

The results are fairly shocking.

- 79% of players failed to get to $250 in 30 minutes, despite that being plenty of time to squeeze in hundreds of coin tosses.

- 28% of players went bust

- two-thirds of players bet on the unfavoured tails at least once

- almost 30% of players bet everything they had on a single coin toss

And all these players were either investment professionals or business students.

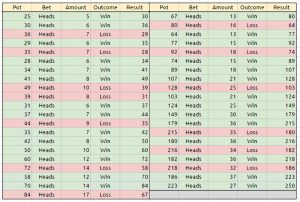

Of course I had to see for myself.

I knew how to bet, and so I always bet on heads.

- I used the round number closest to 20% of my pot as my bet, to save time on mental calculations.

- Whenever I got close to the ceiling of $250, I reduced my bet to limit my risk.

Despite a frustrating section near the end where I was always one or two wins from completing the game, It took me only four minutes to turn $25 into $250.

- Yet more evidence that I’m a replicant.

It took me 41 bets, of which I won 28.

- That’s 68% of the coin-tosses, so I was a little lucky.

- My longest winning streak was four, which happened twice.

- My longest losing streak was two.

I think this game could be as significant in predicting your success in the markets as is the marshmallow test.

- What the other players tended to do was start out in a disciplined manner, but lose faith after a string of losses.

The basic lesson is that you need to avoid emotion and stick to the knitting, riding out the short-term fluctuations.

- As your pot size increases, keep a constant proportion (more in absolute currency terms) invested in risky assets.

This is particularly important towards the end (as you near your retirement target) since the fluctuations here are larger in absolute terms.

Of course, if like the blackjack player you can read the macro runes and work out when the odds are in your favour, then you can always bet large when those occasions roll around.

- But that’s easier said than done, and for the rest of us, the motto is “steady as she goes”.

Food banks

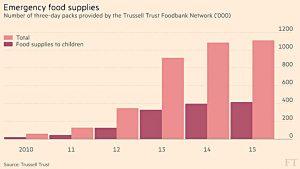

Naomi Rovnick looked at the growth in the number of emergency three-day food parcels distributed by the largest food bank network, the Trussel Trust.

- Food bank vouchers are handed out by doctors, social workers and health visitors to people they feel are “in crsis”.

- They can cash these in for food parcels at community centres, churches, and the occasional “shop”.

Not surprisingly, as the national rollout of these emergency services has progressed, the number of parcels handed out has increased dramatically, as has the amount of food supplied to children.

- More than 1M parcels were given away in 2015, compared with around 50K in 2010.

The Trust’s angle for releasing this data, as well as for commissioning a study from Oxford, is that they would like the government to stop using withholding of payments as a sanction against benefit recipients who won’t follow the rules (like turning up for jobcentre appointments or job interviews).

Unfortunately there are two problems with the Trust’s interpretation: (( And the increasingly leftie FT’s uncritical swallowing of it ))

First, you can’t read anything into a rise in “demand” for a service which is free, as the queues in A&E departments up and down the country testify.

- Once the social workers have free vouchers to dole out, the vouchers will be doled out.

- It says nothing about how many people are going hungry, or why.

Second, what alternative sanction would the Trust recommend?

- Withholding cash is the only lever society has over welfare claimants, since they are already non-contributors.

- Does the Trust propose that people who don’t follow the rules should be treated the same as people who do?

- How far out into society would they like to see this principle applied?

Super Isa

The FT also gave space to Tom McPhail of Hargreaves Lansdown to argue that the many flavours of ISA (Cash, alternative finance, stocks, Help to Buy and now Lifetime) should be combined into a single “Super ISA” able to hold all types of assets.

- A lot of the article was about the LISA, and I agree with Tom that it risks drawing contributions away from pensions, which are better for most people.

He also wants the lifetime allowance on pension pots scrapped (so do I) and wants everyone capped at £20K contributions into pensions (a bit low for me, since lots of people only really get started in their 40s).

Most “interestingly”, he wants tax relief to be age related rather than income related, with the government offering a top up of “100 minus your age” per cent.

- So a 50 year old would get a 50% bonus, bringing their £20K contribution up to £30K.

- Someone aged 25 would get a 75% bonus, increasing their £20K to £35K.

Tom says this scheme is cost-neutral.

- I’m not sure that will be enough to get Philip Hammond to bite in the upcoming Autumn Statement.

Pension Freedoms

Merryn looked at George Osborne’s Pension Freedoms, now 18 months old.

- She’s in favour of the simplifications, as am I.

The big change was the ability to take as much as you liked out of your pension pot from age 55, rather than being pushed towards a poor-value annuity.

- Pensioners seem to have taken George up on the offer, with “flexible withdrawal” now the default strategy for most people.

But Merryn points out that we can’t really know if this is a good thing (( By which I think she means sensible – surely people having the freedom to do what they want with their own money is a good thing in itself ? )) without looking at the detail.

- What percentage of their pot are they withdrawing and from what age (ie. will the pot last) ?

- And what are they spending it on (long-term or short-term things) ?

The average withdrawal is £10K, which doesn’t sound much until you realise the average pot is less than £40K.

- The bad news is that one in three people are just dumping the cash in a savings account.

- Fair enough if you have no rainy-day pot, but otherwise not sensible in the long run.

Merryn thinks that access to DC pots should be aligned with the state pension age, but as someone who retired at 50, I have to disagree.

- The prospect of waiting another 16 years to get my hands on my cash (( I missed out on the pot being available at age 50 – as they used to be – by only six months )) would have been unbearable.

- One year in, I haven’t withdrawn anything yet.

- My plan for this tax year is a modest 5% of the pot, some of which I will reinvest in a (stocks and shares) ISA.

Merryn also points out that the continued focus on your pension pot through 30 years of drawdown is a big improvement on the old system of “annuity conversion day” being the one day most people were interested.

- She also hopes that people will notice that 1% pa fees are significant compared to 3% to 4% pa of drawdown income, and that the industry will be forced to come up with cheaper solutions.

Which brings her to Daniel Godfrey’s The People’s Trust.

- This is a new conviction investment trust which aims to return 7% pa with low charges.

- Sadly, starting an investment trust is not cheap and Godfrey is crowdfunding the first £100K of costs.

Even then the initial fees will be 1% pa, so this is more something to watch for the long term.

Merryn also gave a plug to Netwealth, which appears to be another robo-adviser.

- That’s where she keeps her ETFs, apparently, so I will add it to the list for my next robo-advisor round-up.

In her MoneyWeek column, Merryn talked about demographics.

- As the proportion of over-60s in a society increases, the rate of GDP growth falls.

We can expect future growth (in the US) to be only 1.5% to 1.75% pa.

- And low interest rates can’t make pensioners start businesses or spend money.

Which means that growth / inflation won’t shrink the massive debts everyone ran up in rescuing the world from the 2008 financial crisis.

Making finance safer

Over to the Economist now, which looked at how plans to make financial systems safer can backfire.

Its focus was cross-border capital flows, which increased from 5% of GDP in 1980 to 25% before the 2008 crisis.

- These send capital from slow-growing rich countries to where it is needed, in developing nations, producing a greater return for its owners.

- But since regulation is weak and capital markets are underdeveloped in these nations, things can easily go wrong.

And protective measures can make things worse.

- Worried about capital flight back to rich countries, developing nations built up FX reserves (eg. of US Treasury bonds).

- But buying these bonds pushed up demand and pushed down yields, lowering global interest rates.

And lower interest rates means more risk-taking in search of yield.

- In 2008, this meant buying “safe” mortgage-backed securities.

- Which in turn meant that when short-term interest rates were raised, long-term rates (on things like mortgages) didn’t budge.

Thus even-higher US rates might be needed, which would draw capital back from emerging economies.

- In addition, high rates increase saving instead of investment, pushing rates back down again.

There are similar problems with capital requirements for banks.

- These reduce lending / borrowing in the countries affected, which simply means that there is more money sloshing around in other countries.

The international goodwill and coordination required to avoid this is in short supply.

Contrarian magazine covers

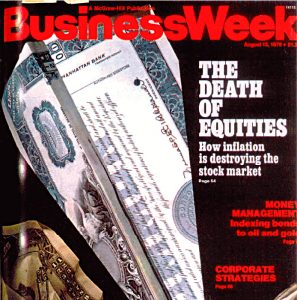

Finally, Buttonwood looked at the long-held theory that when a story makes it to a magazine cover (( Or lead the evening news on the BBC )) it’s already over, and it’s time to think and do the opposite.

- They used the famous “Death of Equities” cover from Business Week in 1979 (three years before the greatest ever bull market got going) as an example.

Two Citigroup analysts who looked at the phenomenon are quoted:

When an editor devotes a cover to a trend, positioning and sentiment should already fully reflect the story, which should be fully priced in.

They used 44 Economist covers from 1998 to 2016 for their study, including the “Drowning in oil” cover of February 1999, which preceded a commodities bull run.

- After six months, there was no noticeable effect – 53.3% had contrarian predictive power.

- But after a year, 68.2% were contrarian.

- Very bearish covers led to 18% gains.

- Very bullish covers led to 7.5% falls.

The Economist has some quibbles over the interpretation of its covers and the appropriate timescales, so head over to the original article for the details.

Until next time.