Weekly Roundup, 22nd March 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with Budget. Our initial reactions to the speech are here, but there are a few things worth looking at in more detail.

Contents

Financial advice

First up is financial advice.

- In the same week that the Budget abolished the free but lightly-used Money Advice Service (and PensionWise), the FCA delivered its Financial Advice Market Review (FAMR).

Naomi Rovnick and Claer Barret each reported in the FT on FAMR.

- The report is concerned with those people in the “advice gap” – which they define as those with less than £100K to invest.

I think the gap is bigger than that.

- Since 2013 the Retail Distribution Review (RDR) has barred independent financial advisers (IFAs) from taking commission from product providers.

Whilst the old system was full of conflicts of interest, and needed to go, the new system doesn’t work for people without lots of money.

- IFAs charge £150 an hour on average, so with typical fees in the £500 to £100) range, only those with upwards of £500K can justify an annual or bi-annual review.

- 85% of investors won’t pay more than £200, and 72% won’t pay more than £100.

- Worse than that, IFAs often turn down willing clients with not so much cash, since the potential fees they can earn are outweighed by the regulatory costs and risks of providing advice.

- Despite this, IFA profit margins average 5% and they spend 12% of their income on regulatory costs.

- 25% of IFAs quit the profession between 2010 and 2014.

The problem stems from the way the IFA profession is structured.

- It’s something of a closed shop, with no way in apart from working for an exsiting IFA.

- It’s also not legal in the UK to receive payment for providing specific financial advice to an individual unless you have gone down the IFA route.

Some people – including the FCA – think that Robo-advice is the way ahead.

It probably is part of the solution (see below) but the current offerings (eg. Nutmeg) are poor value for money, especially for those with “small” pots of £50 to £100K.

- They offer quite rudimentary portfolios at higher costs than a private investor could put together for himself.

I think we need a third way, where lightly qualified independent practitioners can provide something that is half-way between education and specific advice.

- This is currently known as guidance, and it’s the kind of thing that that platforms provide to their paying clients – I think this should be extended beyond the platforms.

- Tailored guidance would build on the Robo-advice approach by collecting most of the client data via the web (via forms and Skype)

- These findings would then be matched against a decision tree of “best practice” solutions, with minimal tailoring to the individual’s circumstances.

- Such a service could be provided for much less than £500, or for an annual percentage (say 0.2%) of the investor’s portfolio, regardless of the underlying products involved.

- Two-thirds of retail financial products are now bought without “professional” financial advice.

Of course, the real problem is financial illiteracy, which goes back to the schools.

- It’s not cool to talk about money in the UK, much less understand it.

- This was fine when people worked one job for 40 years, and paternal employers looked after their retirement.

- Things have changed and people need to take responsibility these days.

- If not, they run the risk of being taken advantage of by a robot.

The good news is that there has never been more information available for free.

- So keep reading the blog, save yourself, and spread the word.

LISA

We touched on the LISA in our Budget review, but for those who want more, Aime Williams and Josephine Cumbo had a double-page spread in the FT.

I’m against the LISA for three reasons:

- it’s age-restricted

- it complicates the existing ISA & SIPP system

- it conflates two incompatible goals – long-term saving for retirement and short-term saving for a house deposit

Here are the facts:

- It’s like an ISA except that the government provides a 25% top-up (equivalent to basic-rate tax relief) on your contributions.

- This pushes it half-way towards being like a pension.

- If you are under 40 on 6th April 2017, you can put in up to £4K a year from ages 40 to 50, and the government will give up to £1K a year on top.

- You can also open a Help-to-Buy ISA now, and roll it into your LISA in April 2017.

- You can invest it in cash, or stocks and shares (like an ISA).

- You can take the money out tax-free (like an ISA again) to buy a house (up to £450K max, so not in central London) or from age 60, to fund your retirement.

So if you are under 39, don’t turn down the free money.

- But check whether a company-matched pension contribution is a better deal first – usually a company pays in at least 100% of your contribution.

And if you are a parent with children over 18, don’t turn down the free money.

- And neither group should leave it all in cash.

If you are a childless homeowner over 40, take comfort from the fact the LISA should support property prices, at least at the bottom end.

Everyone else, as you were.

El-Erian

Merryn had a bit more detail on Mohamed El-Erian‘s policy prescriptions from his book The Only Game in Town, which we touched on last week.

- El-Erian spoke at a lunch that Merryn attended

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=030022253X]

His number one recommendation – for the US at least – would be the reform of Corporation Tax, which is very high over there.

Which brings us back to the budget, because that’s exactly what Osborne did.

- The UK’s rate of 17% by 2020 will be the lowest in the G20.

- There was also good news on business rates.

The other budget change that Merryn talked about was the cut in capital gains tax (CGT).

- This could have an impact on investment in the UK, where income funds are always top of the charts, and FTSE-100 “bond proxies” are under pressure to maintain the dividend whatever happens to the underlying earnings.

Taxes on dividends have been raised from April, so perhaps people will start looking for investments that are CGT-friendly instead.

Compounding

Tim Harford looked at compound interest.

- He began with Warren Buffett’s 1963 letter to shareholders ((We haven’t made it back that far yet in our own series about the letters )).

Buffet said that while the $30K or so invested by Queen Isabella in Columbus’ voyage to the Americas would appear to have generated good returns, if she had instead invested the money in something that compounded at 4% pa, by 1962 she would have had $2 trn.

Tim points out that there are few old money billionaires near the top of the pile.

- It’s not because 4% compounding wasn’t available to them

- Thomas Piketty’s book Capital in the Twenty-First Century suggests that the average return over the past five centuries is 4.3% pa

- This would give Queen Isabella $110 trn today, more than 1,000 times what Bill Gates has

- It’s also half the household wealth of the whole planet

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=067443000X]

Piketty’s book introduced the equation r > g (return greater than growth), which suggested that the rich should get richer over time.

- This has been true apart from the 20th century, which had high growth rates and lots of capital-destroying wars and communist revolutions

The problem with the formula is that money is not passed down only to the first-born son anymore.

- Each cycle of inheritance divides the billions amongst several people

- And most of these trust-fund kiddies spend the cash

The “marginal propensity to consume from wealth” is around 3% pa.

- So wealth really compounds at 1.3% pa

- Which would leave Queen Isabella with “just” $25m – enough for a good time, but not enough to cure malaria

So Piketty’s theory that wealth will be ever more concentrated looks unlikely.

- And getting a safe 4.3% pa on your cash looks impossible these days

US stocks back to over-priced

John Authers noticed that as of last Friday, US stocks were back where they started the year, having bounced back from a 10% fall in a dramatic-looking V-shaped recovery.

It’s been an interesting first quarter of 2016:

- oil is 50% up from its January low

- the Chinese renminbi has strengthened slightly against the dollar

- central banks are running out of interest-rate ammunition, with Japan and Europe both having negative rates but strengthening currencies

- gold is up

- core inflation in the US is now up to 2.3% – the highest since Lehman’s went bust – providing some support for future interest rate rises

- US corporate profits have been disappointing

- so share buy-backs are back

Defensive stocks – the “Dividend Aristocrats” have led the market, in contrast to the tech titans of 2015.

- But the main point to note is that US stocks remain more expensive – on a PE of 18 – than before the 2008 crash.

Buttonwood also looked at the state of the markets.

- Emerging markets are also back where they began the year, and junk bonds yields have fallen.

The fear of global recession seems to have been replaced with expectations of slower, but still positive, growth.

Political risk will cap the scope for a further equity rally for much of 2016, but without the global recession, there should be no crash.

Brexit briefing

This week the Economist’s Brexit briefing looked at sovereignty and democracy.

Both sides agree that sovereignty is an issue.

- The Remain campaign believes that the concessions on “ever closer union” are enough.

- The Leave campaign thinks that a 5% to 10% hit to GDP is a price worth paying to regain control of our destiny.

When Britain joined the EU, Ted Heath said that sovereignty wasn’t an issue.

- But this is true only in the sense that Britain’s Parliament can repeal the 1972 European Communities Act (as it will if there is a No vote in the referendum)

- And European law outranks national law.

But EU membership is not the only treaty that restricts Britain’s actions – membership of NATO creates obligations too.

Democracy is another thing entirely.

- Although the unelected bureaucrats of the European Commission draft EI law, it must be ratified by the Council of Ministers (national EU government members) and the European Parliament (which is elected).

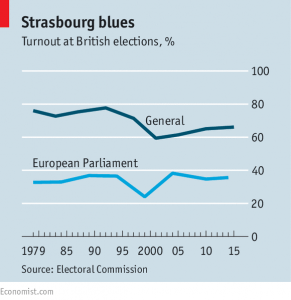

The problem is that there are no real EU-wide elections.

- Elections to the European Parliament are fought by national parties, on national issues

- Voters have no ability to overthrow the EU “government”

- Allegiances in Brussels are poorly-understood in Britain

- And the EU elections turn-out is low

A further problem is that Britain has no history of coalition government, and voters prefer holding a single party responsible for policy.

- This is exacerbated by the demise of the veto, and Britain being outvoted so often these days.

- Cameron has responded with the 55% national majority “red card” concession though it is hard to imagine Britain managing to get 55% of 27 governments to agree on something.

More on Brexit next week.

Blockchain

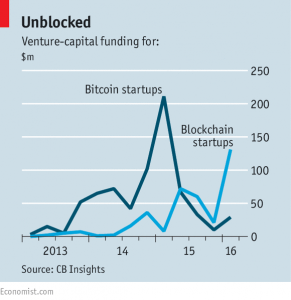

The Economist wrote about the high hopes withing the financial community for the blockchain – the distributed ledger that underpins Bitcoin.

There’s lots of excitement, lots of conferences and lots of venture capital money heading in that direction, but real-world progress is likely to be slow.

The advantages to banks would include a single centralised ledger (rather than one each as now) and instant settlement without intermediaries.

- This should be cheaper and less risky

- It should also make money laundering more difficult, as the ledger contains a list of all previous transactions

Central bankers are also looking at blockchain ledgers – private ones this time – to allow entities other than banks to trade with them directly.

- This could increase currency security (accounts would be guaranteed) and reduce costs (of banknotes)

- It would also make issuing “helicopter money” straightforward

Problems include scalability – the blockchain doesn’t have the capacity of the credit card systems.

Another issue is encryption and privacy – few customers would like their trading records made public.

There’s probably another five to ten years to go before the blockchain is in widespread use.

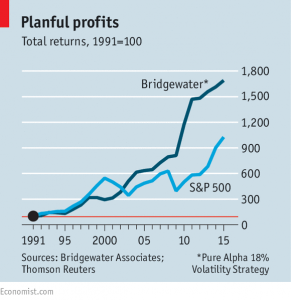

Bridgewater and Dalio

Bridgewater is one of the most successful hedge funds ever, with $154 bn under management.

The Economist reported that its founder Ray Dalio – who we profiled a few weeks back – has promised to hand over both majority ownership (already completed) and control (a work in progress).

- Co-CEO Greg Jensen complained that the transition was going to slowly and was demoted for his pains.

- Both Jensen and Dalio claim all is well, and that these kinds of spats are part of the company’s open culture.

- Dalio maintains he wants to move into a mentorship role.

Time will tell, but there are few examples of successful transitions in hedge funds.

Big Data and inflation

Measuring inflation is tricky:

- the “basket” of representative goods needs to be assembled

- prices of these goods need to be tracked

- new products and changing tastes need to be reflected

- substitutions of things that rise in price by cheaper alternatives need to be factored in

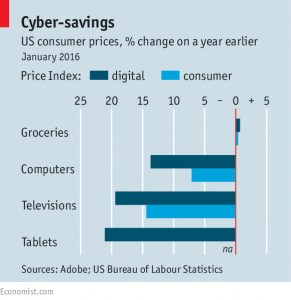

The Economist reported how big data might help.

In the US, prices are measured manually (people visit shops and write them down) and the basket changes ony every three years.

- Yet almost every purchase is already logged in a database somewhere.

Adobe wants to stitch these databases together.

- It already receives anonymised data on 75% of online spending from the top 500 US retailers.

There are a couple of obvious advantages:

- Adobe tracks 1.4M items, rather than the 80K in the basket

- Adobe uses actual transaction prices rather than advertised prices

- And the volume of data allows for more sophisticated statistical techniques to model substitution

Since it doesn’t track things like rent or petrol, the new index will likely work alongside the standard CPI.

- But some things bought mostly online (computers, say) already seem to be tracked better by the new index

- The implication is that inflation as a whole is lower than the offline world would suggest

- And if inflation is lower, but spending is recorded properly, then real GDP must be growing faster than was thought

Big data with big implications.

Productivity

Are low wages caused by low productivity, or are they a symptom? Both, according to the Economist.

- GDP goes up when countries produce more stuff worth more money per person.

- This hasn’t happened much since the 1970s.

- Which is part of the reason that pay has stalled.

There are three theories behind the end of gains.

The first is that modern tech can’t compete with the transformational impact of electricity and indoor plumbing.

- Moore’s law powered increases in the 1990s, but Facebook and Twitter can’t provide the same boost.

- The may be some hope here for robotics and AI to come to the rescue.

- And there is a problem that this doesn’t explain a fall in productivity in marginal countries such as Turkey and Mexico.

The second theory is one of mismeasurement.

- Many digital gains have no impact or in some cases (eg. the falling cost of digital media) a negative impact on GDP.

- The difference in quality between a 2006 phone and a 2016 phone is not captured (from some angles, this exclusion is legitimate, since most tech isn’t made in the developed world).

- As someone who has been on the planet for quite some time, this theory holds water – so many things that were too expensive to imagine or too difficult to achieve are now available to everyone.

- I can get much more done in a day than thirty years ago, but very little of it would count towards official measures of productivity.

- So economists don’t think that the invisible tech bounty is large enough to explain the missing productivity gains.

The third theory is that capitalism’s “creative destruction” has stalled.

- Startup formation has stalled, and fewer firms ever grow big.

- Planning laws appear to restrict the movement of labour from stagnant towns to dynamic ones – San Francisco could be made five times larger if there were no restrictions.

But what about the link in the opposite direction?

- Low pay supports the creation of marginal jobs and works against investment in software and robotics that might improve productivity more.

If so, the looming increases in the minimum wage – on both sides of the Atlantic – should change things for the better.

Tesla

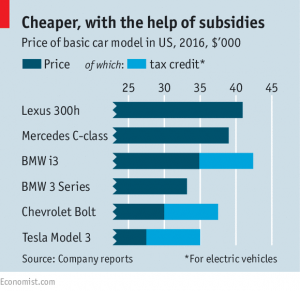

The Economist thinks that electric car firm Tesla is in for a bumpier ride as it approaches the mainstream.

- The Model 3, aimed at the top of the mass-market (it costs $35K before whatever government subsidies will be available), is due to launch at the end of the month.

- Tesla aims to increase sales from 50K a year in 2015 to 500K a year in 2020.

- But its new market segment has more competition and slimmer margins.

Tesla has done well to date.

- The firm is run frugally.

- Elon Musk uses his personal brand to keep the company in the headlines.

- It has cut the costs of batteries, and its new Nevada “Gigafactory” should cut them some more.

- Its big sports saloons sell well.

But it has no direct competitors at present, and Apple and the other luxury car firms are planning their market entry, perhaps in partnership with Google.

- And Tesla’s vertical integration is unusual and capital intensive – car makers nowadays focus on design and brand, bolting bought-in parts together.

- Tesla sells directly to the public, rather than through dealers, which could be more profitable but will again need more cash.

- Tesla even runs its own network of 3,500 free charging stations (I counted 7 inside the M25, with the nearest to me rather inconveniently at a hotel in Tower Hill, a place I never visit).

This all pushes profits off into the future, despite the $29 bn market cap (half of GM’s).

The Economist speculates that perhaps Tesla wants to create a software platform used by other manufacturers (think Android) rather than a winning car.

- But is there enough money in that, assuming that Google and Apple are the competition?

Valeant

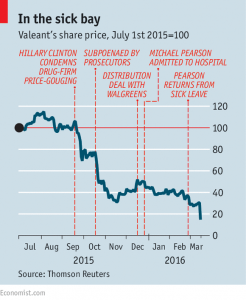

Valeant, the US-listed Canadian drug firm is now the biggest corporate disaster since Lehman Brothers, according to the Economist.

- Shareholders have lost $75 bn and a debt default looks possible.

Valeant bought other drugs firms with debt, cut costs and put up prices, attracting the attention of Hilary Clinton.

It also had dodgy accounting, including a strange relationship with pharmacy Philidor and a low tax rate.

- It has now been announced that the accounts will be restated and filing has been delayed.

- The CEO is also leaving.

- Recent numbers suggest that cash flow only just matches the interest bill.

- Worried suppliers and customers might just push the firm over the edge.

Rival Allergan had warned about Valeant’s finances back in 2014, yet in March 2015, Valeant was able to successfully issue $1.5 bn in shares.

It’s a particular embarrassment for activist investors Bill Ackman (Pershing) and Jeffrey Ubben (ValueAct).

- You might want to make a note that Ubben is currently also active in Rolls-Royce.

Until next time.