Weekly Roundup, 18th October 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about UK farmland prices.

Contents

UK farmland

This week the papers were full of what the fall in the Sterling exchange rate against the dollar might mean for the UK economy.

- We covered this last week, but we’ll return to the topic later.

Meanwhile, James Pickford looked at UK farmland prices, which have stalled after rising sharply for more than a decade.

- The peak of £8,300 per acre was in September 2015, and prices have now slipped by 8% to £7,672 per acre.

But it’s not down to Brexit.

- Instead, the slump in soft commodity prices (wheat, milk and lamb) over the past two years is probably to blame.

- Brexit might even help a bit in the short term, since exports should be boosted by the fall in sterling (of which more later).

Of course, once EU subsidies – which account for a staggering 77% of UK farm income – have ended, things could get worse.

- It’s quite possible that farms at the bottom end of the productivity spectrum will have to close, unless the UK adopts a “food security” policy and replaces some of the EU subsidies with those of its own.

Help the youth

Elsewhere in the FT, we had three separate articles looking at what could be done to help young people.

Josephine Cumbo revisited the pensions changes that could happen in November’s Autumn Statement.

- Higher-rate tax relief could be replaced with a flat rate (30%?) for everyone.

Hargreaves Lansdowne suggests top-ups instead, at a rate of “100 minus your age” per cent.

- So a 25-year old saver would get a top up of 75p for every (post-tax) pound they contributed, whereas a 50-year-old would only get a 50p top up.

- These are equivalent to tax-relief at 43% and 33% respectively.

I suspect they will sound too high to the chancellor, and a flat 30% (or even 25%) is more likely.

- Even more likely is a focus on Brexit and auto-enrolment, with no pensions changes.

- There could be an extension of the Lisa to help the youth.

Any higher-rate tax payers who are worried should make their payments now.

- Conversely, basic-rate taxpayers would do well to wait.

Lindsay Cook’s article mostly covered her personal history with property, but in the end she made a plea for the return of the stamp duty exemption for first-time buyers that we had from 2010 to 2012.

- As an alternative, the system used on shared-ownership properties (pay when you own 80% of the equity) could be brought in.

Although in principle I’m against market interventions like this, I’m a great believer in people owning their home, for social cohesion reasons.

- So giving them a bit of help is fine with me.

Looking at the bigger picture, stamp duty – like all transaction taxes – is silly.

- All it does is encourage people to stay in the home they have.

- This is particularly true at the top end of the market.

Locking up a market through taxes is rarely a good thing for the economy.

Kate Allen wanted to see more flexibility in pensions and mortgages, to suit the “mobile generation”.

- The old-style 25 year mortgages and DB employer pensions are more suited to the days of lifetime employment with the same firm.

Because more workers today change jobs and towns every few years, lots of people reach their late thirties with no house and no pension.

Kate wants to see more portability in pensions, and sees the LISA as a step in the right direction.

- I think the LISA is a distraction designed to prop up the housing market.

- Higher (and possibly compulsory) contributions to the new auto-enrolment employer pensions would be a better way to go.

- Making those pensions more portable would obviously be a good thing.

On the mortgage front, Kate worryingly talks of “alternative lenders” (she mentions Brighthope) who target those “who find it hard to meet traditional mortgage lenders’ credit criteria”.

- She means the self-employed, and I have some sympathy there – I certainly struggled to get a mortgage when I was a consultant in the 1990s.

- But at the same time, there’s a whiff of sub-prime here – how do we make sure that easy credit doesn’t go to people who will never be able to pay it back?

The good news is Kate also wants the chancellor to “lower the transaction costs for home ownership” – that sounds like stamp duty to me – and to “make it the norm to part-own”.

- In a sense, most people part-own to begin with, since the mortgage company really has the majority of the equity.

- So like any measure designed to get people on the housing ladder, this one runs the risk of inflating prices even further.

The scheme would need to meet rules on the minimum equity percentage at the start of the deal, and the progression towards full ownership as people get older.

- Otherwise the people who today can only afford three-quarters of the house they want will end up owning only half of the same house at an even greater price.

Nobel prize for economics

This year’s Nobel prize for Economics has been awarded to Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmstrom for their work on contract theory.

- The Economist explained why – they studied economic power, and how people keep their self-interest under control when trying to work together.

Mr Hart in particular struggled to explain the existence of companies.

- They must provide some advantage over a cash market for the exchange of services in order to exist, but it’s hard to identify what the advantage might be.

The problem with contracts is in foreseeing all possible future situations that you might want the contract to cover.

- Mr Hart explains that bargaining power (such as ownership of key assets) gives one side the advantage when it comes to windfall profits.

- Workers in a factory accept wages in the knowledge that the owners of the buildings and machines will take a bigger share of profits.

Mr Hart used this theory to explain why private prisons might be a bad idea – owners are directly incentivised to cut costs (and hence inmate care) since their profits will increase.

- Fans of free markets might argue that if there were several private prison companies, and inmate care could be adequately defined, competition to drive down costs would be a good thing.

- And if one or more firms failed the adequate care test, their prisons could be taken over by other firms who didn’t.

Mr Holstrom looked at individuals (principals) who need someone else (agents) to do something for them.

- Getting the incentives right so as to produce the desired behaviour in the agent is not easy (the famous agency problem).

- Linking executive pay to profits or share prices is a bad idea, since they are driven by other factors than executive performance.

Measures relative to rivals and industry averages are a much better idea.

- The problem is that some of the most important indicators (brand reputation or product quality) are harder to measure, and hence to incentivise.

US jobs

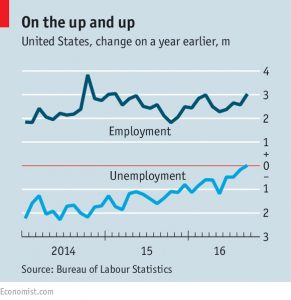

The Economist also looked at why America is managing to create more jobs without unemployment falling.

- Employment is up by 3M over the last year, but unemployment remains around 5%.

That’s because the labour participation rate for 25- to 54-year-olds is up by 1%.

- This is the fastest growth in Americans seeking work since 1989.

The peak for participation was 84.6% back in 1999.

- From there to 2015 it fell by more than 5%, at 0.2% pa.

So there could be a lot more of this to come.

- 1.8M people say they want a job, but haven’t been looking for one.

- But at the moment, participation growth is coming from a growing population, and a lowered likelihood that the long-term unemployed will quit.

- People aren’t getting off their sofas just yet.

Working against this possibility is the ageing of the workforce.

- Those aged above 45 are less likely to work, and there are more of them these days.

- On top of this, many have poor health

- And a new paper suggests that a lot of younger men would rather play video games than work.

It’s not easy to interpret all of this, but it suggests that the Fed shouldn’t be in too much of a hurry to raise rates.

- Waiting for a fall in unemployment might be the safest option.

Inflation-linked annuities

MoneyWeek demonstrated that inflation-linked annuities are only good value when there is serious inflation about.

- A 65-year-old man would get £3,501 pa from a level annuity, but only £2,072 from an inflation-linked one.

Life expectancy at 65 is 19 years.

- With inflation at 0.3% (as it was a couple of months ago – CPI hit 1.% this morning), the linker would only be paying £2,186 at age 84, still much less than the level annuity.

- By this point the flat annuity would already have paid out £27.5K more.

Even with inflation at 2% (the Bank of England’s target), the linker would only be paying out £3,017, and would be £19,700 behind in terms on income already paid out.

- On the other hand, with inflation at 5%, the linker would be paying out £5,233 at age 84, and would draw ahead in payouts that year.

Valuing currencies

As a little preamble to the sterling “crisis”, Mathew Partridge of MoneyWeek looked at how to value currencies.

His first port of call was the Economist’s “Big Mac Index”.

- The idea is that goods should cost the same everywhere in the world, after taking the exchange rate into account.

- This is known as the law of one price.

The Big Mac was chosen because it’s a standardised product using local inputs (food and labour).

- So if the Big Mac is £3 in London and $4.50 in New York, the exchange rate should be £1=$1.50.

In fact the Big Mac is ((Actually was in July, when the Economist last published its survey )) £2.99 in London and $5.06 in New York, suggesting a fair exchange rate of $1.69, compared with the $1.22 it’s at today.

- But if you use an iPhone instead of a Big Mac, the implied rate is only $1.08.

- The “average” number is a thing called “purchasing power parity” (PPP) which looks at a basket of goods.

The PPP fair value is $1.45, and we can reasonably expect the pound to move towards the PPP figure over the long term.

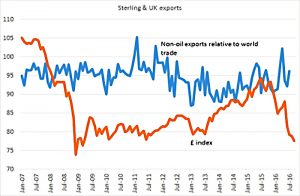

Sterling crisis

And so finally to the pound. Last week we concluded that:

- we can expect some inflation from pricier imports- perhaps 1.5% pa, to take us from last month’s 0.6% to 2.1%

- interest rates may push up from 400-year lows

- gilts may fall from extreme highs, potentially pushing up the cost of the new governments proposed stimulus package

I don’t have the space or time to cover the dozens of articles that appeared this week, but let’s have a quick look at a few of them.

In the New York Times, Paul Krugman didn’t think the “pound plunge” would lead to recession.

- The predicted investment demand collapse hasn’t happened.

Instead he focused on the “home market effect”.

- With a product that has scale economies and is produced in two countries, you would produce it in the large country to minimise shipping costs.

- The smaller country would pay lower wages to maintain competitiveness (effectively using a weaker currency to compensate for its smaller market).

Krugman sees financial services – which London dominates in Europe – this way.

- Britain needs a weaker currency to offset the risk of financial services returning to Europe.

This is not all bad, since the City’s ability to keep the pound strong has hampered UK manufacturing.

- So while London might suffer, the regions (who voted for Brexit) might do better.

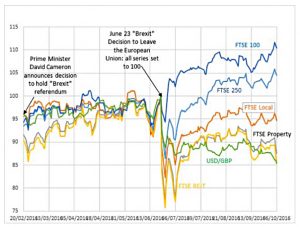

In the Independent, Ashoka Mody argued that the weak pound was good news.

- He sees the pound’s fall as driven by speculative money leaving the property sector.

- This should cause a rebalancing towards “productive enterprise”.

As evidence, he contrasts the movements of listed property assets (broadly in step with the exchange rate) with those of for example the FTSE-100 (broadly the inverse).

The finance-property “bubble” that led to the over-valuation of the pound meant that though Britons felt rich when buying goods and services abroad, they were really living beyond their means.

- Britain was spending more than it was producing, and UK external debt rose to 300% of GDP.

Ashoka points out that the 20% previous overvaluation of the pound make the Remainers’ concerns over a few points of EU tariffs beside the point.

Over on mainly macro, Simon Wren-Lewis examined both arguments.

- The logic involved is fine, but Simon expects Brexit to make exports more difficult across the board.

- Which makes Brexit a bad thing in his view.

If you are a glutton for punishment, here are few more links worth following:

- Alasdair Macleod – How not to manage a currency

- John Stepek – What sterling’s nosedive means for your money

- Economist – Taking a pounding

- Buttonwood – Why sterling suffered a “flash crash”

- Merryn Somerset Webb – Cloud over the pound has a silver lining

- Chris Dillow – Sterling’s effects

- Robin Wrigglesworth – Poundemonium

- Angus Armstrong – Pound in your pocket

Quite a spread of views, and most of them worth considering.

- I’m still not worried – perhaps that’s a bad sign.

Until next time.