100 Baggers 3 – Owner-Operators, CEOs and Buffett

Today’s post is our third visit to 100 Baggers by Christopher Mayer.

Skin in the Game

Chapter 7 of Mayer’s book looks at owner-operators. He quotes Martin Sosnoff:

Entrepreneurial instinct equates with sizable equity ownership. If management and the board have no meaningful stake in the company – at least 10 to 20% of the stock – look elsewhere.

Mayer notes that stocks with high insider ownership are often less liquid, and therefore often underweighted by ETFs.

- Most indices use a free-float market cap, which means that owner-operator companies are underweighted.

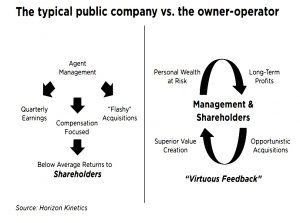

Money manager Peter Doyle of Horizon Kinetics says:

We’re finding these owner-operators are being priced well below the marketplace, yet they have returns on capital far in excess of the index.

The good news is that when/if the insiders sell, ETF interest could rise, pushing up the stock price.

- Ironically, this is the opposite behaviour to what you would ordinarily want (buying when insiders sell rather than following them).

Mayer lists several studies which found that stocks with high insider ownership have outperformed.

Murray Stahl and Matthew Houk, managers of The Virtus Wealth Masters Fund say:

By virtue of the owner-operator’s significant personal capital being at risk, he or she generally enjoys greater freedom of action and an enhanced ability to focus on building long-term business value (e.g., shareholders’ equity).

The owner-operator’s main avenue to personal wealth is derived from the long-term appreciation of common equity shares, not from stock option grants, bonuses or salary increases resulting from meeting short-term financial targets that serve as the incentives for agent-operators.

Outsiders

Chapter 8 looks at CEOs.

Mayer refers to a book about them:

- The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success, by William Thorndike.

Thorndike profiles eight CEOs. Four of their stocks became 100-baggers under their watch. These CEOs include Henry Singleton at Teledyne (180-bagger), Tom Murphy at Capital Cities (204-bagger) and John Malone at TCI (900-bagger). Oh, and Warren Buffett.

There are also four who don’t quite make the cut of being a 100-bagger, such as Katharine Graham at the Washington Post (89-bagger) and Bill Stiritz at Ralston Purina (52-bagger).

Most of the CEOs in the book made investors a lot of money, and the thesis of the book is that they were all great capital allocators (ie. investors).

CEOs have five basic options, says Thorndike: invest in existing operations, acquire other businesses, pay dividends, pay down debt or buy back stock.

Mayer introduces the sixth option – waiting or sitting on the cash.

They also have three ways to raise money: issue stock, issue debt or tap the cash flow of the business.

Thorndike draws a couple of relevant conclusions:

- value per share is what counts, not overall size or growth;

- cash flow, not earnings, determines value;

He also approves of decentralised organisations, and patience plus occasional boldness.

- The CEOs were often based outside of New York, which helped to blot out the noise.

- Simplicity was a theme.

Mayer concludes:

There is no exact formula, [but] they “disdained dividends, made disciplined (and occasionally large) acquisitions, used leverage selectively, bought back lots of stock, minimized taxes, ran decentralized organizations and focused on cash flow over reported net income.

Mayer asked Thorndike about future 100-baggers. Here’s the list of companies, almost none of which I recognise:

- TransDigm

- Danaher

- Colfax

- Valeant

- NVR

- Exxon Mobil

- Leucadia National

- Autozone

- Constellation Software

An 18,000 Bagger

Chapter 9 looks at Berkshire Hathaway.

The stock has risen more than 18,000-fold, which means $10,000 planted there in 1965 turned into an absurdly high $180 million 50 years later.

For this chapter, Mayer refers to another book: The Warren Buffett Philosophy of Investment, by Elena Chirkova.

As Mayer admits:

It’s tough to hoe fresh ground in Buffett-land.

Chirkova’s contribution is to focus on BRK’s use of leverage. She says:

The amount of leverage in Berkshire’s capital structure amounted to 37.5% of total capital on average.

Regular readers of Buffett’s annual letters will know this comes from the insurance float.

As an insurer, you collect premiums upfront and pay claims later. In the interim, you get to invest that money. Any gains you make are yours to keep.

More importantly, it’s cheap money:

Buffett consistently borrowed money at rates lower than even the US government. If premiums exceed claims, then Buffett effectively borrowed money at a negative rate of interest.

From 1965, according to one study, Berkshire had a negative cost of borrowing in 29 out of 47 years. Chirkova cites another study that puts Berkshire’s cost of borrowing at an average of 2.2 percent — about three points lower than the yield on Treasury bills over the same period.

It’s hard not to do well when nearly 40 percent of your capital is almost free.

This required BRK to stand firm on what insurance business it was prepared to underwrite.

To pay those low rates required the willingness to step away from the market when the risk and reward got out of whack.

It’s a nice take on BRK, but hard to generalise to other 100-baggers.

That’s it for today.

- We’ve covered another twenty per cent of the book and we’re still on track to finish in five articles (plus a summary).

We didn’t learn much today.

- We put a potential floor on insider ownership (10%) and reiterated EPS and cash flow as key indicators.

Until next time.