100 Baggers 4 – Kelly, BuyBacks and Moats

Today’s post is our fourth visit to 100 Baggers by Christopher Mayer.

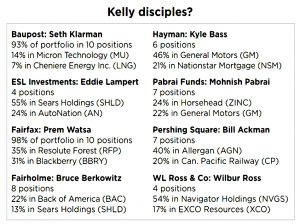

Kelly

Chapter 10 is about bet sizing and the Kelly criterion. Mayer quotes Phelps:

Be not tempted to shoot at anything small.

But this is a quote about selectivity rather than portfolio size.

- Phelps doesn’t want you to buy potential 10-baggers rather than potential 100-baggers, but he says nothing about how many potential 100-baggers you should invest in (I would say as many as you can find).

You can read more about Kelly and his theory in William Poundstone’s book Fortune’s Formula.

Kelly’s answer reduces to this, the risk taker’s version of E = mc2: f = edge/odds. F is the percentage of your bankroll that you bet. Your edge is your profit divided by the size of your wager.

Or looked at another way, when you have a good thing, you bet big.

Many people – including Mayer – find Kelly too aggressive and use the “half-Kelly” rule instead:

It cuts the volatility drastically without sacrificing much return. A 10 per cent return using full Kellys turns into 7.5 per cent with half-Kellys. The full-Kelly bettor stands a one-third chance of halving her bankroll before she doubles it. The half-Kelly bettor has only a one-ninth chance of losing half her money before doubling it.

The issue in applying Kelly to 100-baggers is calculating your edge – what are the chances that your stock choices will actually become 100-baggers?

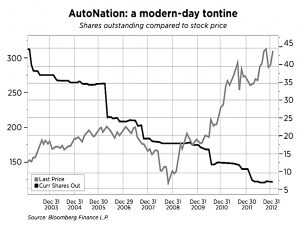

Buybacks

Chapter 11 is about buybacks, but it starts with tontines.

We’ve looked at these before – they are a “death pool” investment, where dividends are split between however many investors are still alive.

- They were banned for a while as they incentivise pool members to kill each other.

Share buybacks have a similar effect, concentrating earnings in the remaining (uncancelled) shares.

- The main problem is that as fast as companies cancel shares, they issue new ones.

Since 1998, the 500 largest US companies have bought back about one-quarter of their shares in dollar value, yet the actual shares outstanding grew. This is because they hand out the shares in lavish incentive packages to greedy executives.

Mayer uses AutoNation as an example of buybacks done right:

He also quotes Buffett on the topic:

There is only one combination of facts that makes it advisable for a company to repurchase its shares: First, the company has available funds – cash plus sensible borrowing capacity – beyond the near-term needs of the business and, second, finds its stock selling in the market below its intrinsic value, conservatively calculated.

The practise has become more common since the 1990s, so lots of Mayer’s 100-baggers didn’t use it.

- But the ones who did showed spectacular results.

Moats

Chapter 12 looks at competitive moats.

- The moat is the thing that allows the 100-bagger to perform well for long enough to reach the 100x milestone.

Companies that are more durable are more valuable. And moats make companies durable by keeping competitors out. A company with a moat can sustain high returns for longer than one without. That also means it can reinvest those profits at higher rates than competitors.

Mayer describes the main types of moat:

- A strong brand (Tiffany’s, Coke)

- Switching costs (banks)

- Network effects (originally Microsoft, now all the internet stocks)

- Low cost (Walmart, Interactive Brokers)

- Size (Intel, Walmart again)

Michael Mauboussin, a strategist at Credit Suisse, has also done some good work on moats.

He says that industry is not destiny:

Even the best industries include companies that destroy value and the worst industries have companies that create value.

He suggests creating an industry map.

For airlines, this would include aircraft lessors (such as Air Lease), manufacturers (Boeing), parts suppliers (B/E Aerospace) and more. What Mauboussin aims to do is show where the profit in an industry winds up.

Mauboussin’s industry analysis also shows that industry stability is another factor in determining the durability of a moat. Stable industries are more conducive to sustainable value creation.

The beverage industry is a stable industry. Sodas don’t get disintermediated by the Internet. Smartphones, by contrast, constitute a very unstable market.

BlackBerry and Nokia are evidence of that.

Mayer sees moats as a way for firms to fight mean reversion (in their excess returns).

- Here, he looks to a paper from Matthew Berry called “Mean Reversion in Corporate Returns.”

This study examined 4000 firms in the US and Europe from 1990 to 2004.

High gross margins are the most important single factor of long-run performance. Scale and track record also stand out as useful indicators.

According to Mayer:

Gross margin is a good indication of the price people are willing to pay relative to the input costs required to provide the good. It’s a measure of value-added for the customer.

If you can’t see how or where a company adds value for customers in its business model, then you can be pretty sure that it won’t be a 100-bagger.

And:

A good turnaround candidate would be one with a high gross profit margin and a low operating margin. The latter is easier to fix than the former.

Bigger companies also do well:

Larger companies appear able to sustain returns for longer by finding efficiencies in SG&A [selling, general and administrative overhead] that small companies cannot.

That’s it for today.

- We’ve covered another fifth of the book, leaving just one more article in this series (plus a summary).

And we’ve added a few more things to look in 100-bagger candidates:

- betting big when you have an edge

- share buybacks

- moats

- high gross margins

Until next time.