Weekly Roundup, 30th August 2022

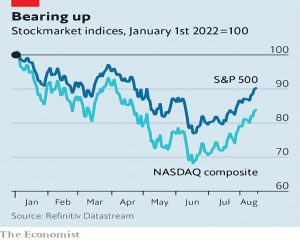

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at the new bull market.

Bull market

The Economist asked whether the new bull market can last.

January to June this year were the worst first half for American shares in more than five decades. The S&P500, America’s leading index of stocks, slumped by 21%; the tech-heavy NASDAQ shed 32%.

But since then, the NASDAQ is up 20% and into a new bull; the S&P 500 have recovered by 17%.

There is some economic justification – earnings have held up pretty well, jobs are still being added and inflation has slowed.

- But inflation stalled because energy costs fell – other stickier prices are still rising.

And we have more rate hikes to come, perhaps before cuts in 2023.

- And the job numbers imply wage pressures on inflation.

Most past market downturns included plenty of breathtaking “bear market” rallies before stock prices resumed their downwards march. In the dotcom bust,

the NASDAQ shed a third of its value between March and April 2000 before surging by more than 20%. The index did not reach its bottom for another two years.

Will this time be different?

Buttonwood explained that investors have no alternative other than to be optimistic about equities, as the alternatives have not delivered.

“Safe-haven” assets fall into two categories. There are physical things with limited supply, guaranteed demand or both: think of gold, or other precious metals.

And then there are promises of value that investors trust to be kept come hell or high water, such as American Treasuries or inflation-proof currencies like the Japanese yen.

Gold is down 3% in 2022, Treasuries are down 9% (even index-linked yields have risen from -1% to +0.4%) and bitcoin has halved. The strong dollar has risen from 115 to 135 against the yen.

- The dollar itself has been a good haven, but that only helps those of us who aren’t American, and it ignores the ravages of inflation.

There’s no silver bullet this year.

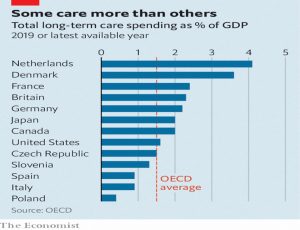

Demographics

The Economist wondered whether rich countries can afford to care for the old without going bust.

- The story focused on Denmark and the Netherlands, which are the two highest spenders at the moment.

At the moment, 1 in 7 of the Dutch workforce cares for the sick and frail, and as the number of over-75s doubles by 2020, this could rise to 1 in 3.

- The government has announced that more care will now take place in the home rather than in a nursing home, which for some reason is more expensive.

I can only assume this is either because more care is provided (perhaps because those in need are frailer), or because the “hotelling” costs are being accounted for in a different way than the costs of living at home.

Two obvious ways to tackle the problem are to claw back rises in property value and to find more care workers through immigration, but neither is popular with voters.

The Netherlands is also keen on the prevention of issues like hip fractures (using smart tech like floors with sensors and belts with airbags).

- Less good is the idea that face-to-face visits are swapped for video calls (which few elderly like).

I’m also not convinced that lifetime care costs will be impacted much since most are incurred in the last few years of life, whether that happens in your 60s or in your 90s.

A third option is the idea of “retirement clusters”, where the old and disabled are offered subsidised rents in return for helping each other out.

- A by-product of this approach is that large houses are freed up for families.

Meanwhile, in the FT, Ian Goldin (professor of globalisation and development at Oxford) argued that demography is not destiny.

For the first time in history there are more people over 65 than under 5. More than half the countries in the world are now below the level of fertility required to keep the population the same from generation to generation.

The working age population of the 38 member countries of the OECD is projected to decline by around a quarter over the coming 30 years.

Longer retirements mean more savings, which dampens demand for everything else. And an increasing share of care work is a drag on productivity gains.

- Ian wants to see more investment in clean infrastructure, health, housing and education, but I’m not sure that will fix things.

Monetary policy

The Economist reviewed and compared a couple of books on monetary policy: The Price of Time, by Edward Chancellor and 21st Century Monetary Policy by Ben Bernanke.

Humans prefer jam today to jam tomorrow. Interest rates are the reward for deferring gratification, for renting out money that could have been spent today. When rates fall too low, grave consequences follow: financial instability, higher inequality and pain for savers.

Chancellor’s book sets out to answer what interest rates should be (as opposed to what they are – which is a level the central bank deems will control inflation).

- But the Economist finds his argument flawed, preferring Bernake’s book which is partly a history of the Fed and partly a study of tools like QE.

For Mr Bernanke, the ultimate determinant of interest rates is the global balance between savings and investment. Rates have been low because desired savings have risen as societies have aged.

For me, these two arguments are not incompatible: morally, lenders (savers) should be adequately compensated, but market forces (including savings gluts) will determine how well they are actually compensated.

- Where things get complicated is when human bankers set interest rates under the influence of politicians who have ulterior motives (keeping national interest bills low and winning elections).

The alternative would be some kind of formula or rule that sets rates automatically according to economic conditions.

- Good luck designing a rule to garner consensus support.

The newspaper points out that the effects of low interest rates (as listed by Chancellor) can be contradictory, but individually they stand up for me:

- They result in the misallocation of capital (and in particular, keep alive zombie firms that don’t earn enough to survive higher rates)

- They encourage more risk-taking since returns from safe assets are low

- They make annuities (and DB pensions) unaffordable

- They push up property prices (and stock prices, too)

- They damage bank profits

Bernanke is on safer ground when he points out that QE alone did not lead to market instability and inflation.

- It took the pandemic – and the excessive government support that was provided – to do that.

Bernanke’s book came out before inflation was a big problem, so he gets this bit wrong.

- I guess we’ll have to wait for Powell’s book to find out whether he would have done things differently in 2021.

Never Sell

This week I came across a 2021 article in the FT written by Drew Dickson of Albert Bridge Capital.

- It’s a response to a piece by Laurence Burns of Baillie Gifford, who argued that “It is usually a mistake for investors to take profits” because “a tiny number of superstar companies account for returns from equity markets.”

This is the BG line on the work of Hendrik Bessmbinder, which we’ve looked at in depth.

Burns is implying that a biased sample of selfselected winners like Tesla and Alibaba suggest that it is a mistake to ever sell any shares in any companies that you think are “winners” either historically or prospectively.

But the other side of the coin is former winners that went bad, like Kodak, Cisco and Nokia.

And Drew doesn’t like Bessimbinder’s data (which says that 4% of stocks are responsible for all gains in total).

These were not the top four per cent of a broad index like the S&P 500, but instead the 25,300 companies that have appeared in the Center for Research in Security Prices over the past 90 years. So that was 1,092 companies, or over twice as many “big winners” as there are in the S&P 500.

And another 9,579 stocks outperformed T-bills.

Bessembinder also claimed that “less than half the names outperformed US Treasuries.”

Well, less than half the names underperformed US Treasuries too. About five per cent of the universe was in line, and the balance was split between the relative winners and the relative losers.

Drew suggests we follow the advice of another BG instead:

Nearly every issue [stock] might conceivably be cheap in one price range and dear in another – Benjamin Graham

Robo Advisors

Daniel Lanyon of alt-fi looked at whether digital disruptors (robo-advisors) have proven the naysayers wrong.

- Even the editor of a fintech newsletter was forced to admit that the answer was “mostly no”.

By 2018 there were about 20 standalone robo advisors or digital wealth managers – mostly independent start-ups offering risk-targeted model portfolios.

These were Nutmeg, Scalable Capital, Moneyfarm, Moneybox, Fiver a Day, Money on Toast, Munnypot, Moola, Wealthify, Wealth Horizon, Risksave, eVestor, Click&Invest, Netwealth, Wealth Wizards, UBS Smart Wealth, ETFMatic, Wealthsimple, Fountain, Tiller, Exo Investing and Rosecut.

85% of that list has stopped trading and the “winners” include some that have been taken over by larger groups:

- Scalable Capital remains a startup unicorn, backed by Tencent and BlackRock – but it no longer trades in the UK retail space

- Nutmeg is the UK market leader, but is now owned by JP Morgan and is still loss-making

- Moneybox is the largest provider of LISAs, but that’s a niche product

Daniel concludes:

Robo advisers in the UK though have largely gone out of business or been acquired. This is true of small, scrappy startups as well as flanker brands launched in-house by large banks with very deep pockets.

Robos have been a real disappointment to me – they charge too much and they are very unsophisticated, offering nothing that a DIY investor couldn’t do for themselves at a lower cost.

Quick Links

I have just three for you this week, all from The Economist:

- The newspaper reported that against expectations, global food prices have tumbled

- And wondered whether the demonised oil industry become a force for decarbonisation?

- And looked at firms’ unwise addiction to mergers and acquisitions.

Until next time.

I am a bit puzzled at the comment that Gold is down 3% in 2022. I am invested in SGLN which is the ishares Physical Gold ETF that shadows the gold price in £ and it has risen from £26.12 at the start of the year to £28.86 as of Friday- I make that a rise of just over 10%: it is one of the few positive investments this year – the FT agrees below:

https://markets.ft.com/data/etfs/tearsheet/charts?s=SGLN:LSE:GBX

Gold is usually priced in dollars so it can be up in Sterling terms, but still down.

The dollar peak was in early March and it looks like we’re down about 5% in 2022.