100 Baggers

Today’s post is our first visit to a new book – 100 Baggers by Christopher Mayer.

Contents

100 baggers

The sub-title of the book is “stocks that return 100-to-1 and how to find them”.

- I would add to that the even if we can find them, hanging on to them while they increase in value by 100 times will be no easy feat.

The plus side is that a 100-bagger will turn £1K into £100K, or £10K into £1M.

- Again, hanging on as this one stock becomes an ever-grater proportion of your portfolio would be difficult.

But if Christopher’s rules work, perhaps we could find a dozen potential 100-baggers, and hang on to the portfolio as a whole.

As usual, my focus in working through the book will be practical lessons that we can apply to our own investing.

- I’m less interested in anecdotes and war stories.

Christopher Mayer

I don’t know anything about Christopher Meyer, who wrote this book back in 2015.

According to Wikipedia, he is an author, former banker and investor.

- He’s been a writer since 1998 and in 2019, he started Woodlock House Family Capital, a hedge fund.

Scope

Chapter 1 is called “Introducing 100-baggers”. Christopher starts by laying out the scope of the book:

You will learn the key characteristics of 100-baggers. You will learn why anybody can do this. I’ll share with you a number of “crutches” or techniques that can help you get more out of your stocks and investing. The emphasis is always on the practical.

So this book is for people who want to find big winners.

Phelps

The inspiration for Mayer’s book is a 1972 book called “100 to 1 in the Stock Market”, by Thomas Phelps.

- Mayer also quotes Peter Lynch’s search for 10-baggers.

In this book, Mayer fakes having interviewed Phelps back in the day, but in reality, the “interview” is a series of quotes from Phelps’ book.

- Phelps died in 1992 at the age of 90.

Mayer describes Phelps as:

The Wall Street Journal’s Washington bureau chief, an editor of Barron’s, a partner at a brokerage firm, the head of the research department at a Fortune 500 company, and, finally, a partner at Scudder, Stevens & Clark (since bought out by Deutsche Bank). Phelps retired in Nantucket after a varied 42-year career in markets.

Phelps found hundreds of 100-baggers, providing you hung on.

- His motto was “buy right and hold on.”

Investors bite on what’s moving and can’t sit on a stock that isn’t going anywhere. They also lose patience with one that is moving against them. Investors crave activity, and Wall Street is built on it.

The key to hanging on – as value investors will understand, even though looking for 100-baggers is a growth strategy – is to focus on the characteristics of the business rather than its market price.

- Earnings per share and returns on equity are more important.

Phelps looked for “new methods, new materials and new products – things that improve life, that solve problems and allow us to do things better, faster and cheaper”.

- The important thing is to understand how a company could create value in the future.

Selling

Phelps was not a fan of ever selling and relayed stories of people regretting selling stock in IBM (a friend) and Polaroid (Phelps himself).

- It’s worth pointing out that at the time of the interview (during the heyday of the Nifty Fifty), “never sell” was apparently good advice.

Never take an investment action for a noninvestment reason. Don’t sell just because the price moved up or down, or because you need to realize a capital gain to offset a loss. You should sell rarely, and only when it is clear you made an error.

But you would have had to sell both of those stocks in the end – IBM is a shadow of its former self and Polaroid went bust in the face of digital cameras.

- The stories remind by of the famous “$50M pizza”, bought with bitcoin b before anybody realised what BTC would be worth.

If we could all see the future, we would never make mistakes – presumably, stock prices would never move.

Phelps also mentioned that his ability to predict bear markets put him off investing in 100-baggers.

Bear market smoke gets in one’s eyes.

Compounding

Phelps had a table showing the necessary compounding rates to get to 100-1 over various timescales.

You either need a heroic growth rate, a very long time horizon, or both.

- Monster Beverage 100-bagged in “just” 10 years, a 50% CAGR.

Updating

Phelps’s book was a study of 100-baggers from 1932 to 1971. He cut out the tiniest of stocks, [but] even so, his book lists 365 stocks. I decided to update his study.

Mayer’s book covers 1962 to 2014, and stocks that started at $50M before they 100-bagged.

- By coincidence, he also found 365 stocks.

Mayer

In the next section, Mayer runs through his own investing background.

- He started off in the Graham/Dodd/Buffett tradition.

He wasn’t tempted by the Market Wizards or Darvas books.

They struck me as freakish. The gains were enormous, but the process was not replicable – certainly not by the everyman.

I have to disagree here – a lot of the processes involved are well understood, though market conditions might not be so favourable as they once were.

- And remarkably, Mayer thinks that the Phelps method is easy to follow.

Anyone can invest in a 100-bagger – and many ordinary people have. Anyone can find them – or find close-enough approximations. After all, who is going to complain if you only turn up a 50-bagger, or even a 10-bagger?

Phelps demonstrated (I won’t say proved) this claim through anecdotes, and I worry that Mayer will take the same approach.

Survivorship

There are severe limitations or problems with a study like this. I’m only looking at these extreme successes. There is hindsight bias, in that things can look obvious now. And there is survivorship bias, in that other companies may have looked similar at one point but failed to deliver a hundredfold gain.

This is true, and hard to correct.

- But at least if you target 100-baggers, a less than 100% hit rate will do you just fine.

This is not meant as a scientific or statistical study. Investing is, arguably, more art than science, anyway. If investing well were all about statistics, then the best investors would be statisticians. And that is not the case.

This is a familiar tale, and yet I would argue that the best investors (Simons, Dalio et al) are indeed quants.

True stories

Chapter 2 of the book looks at reader emails about their own 100-bagger stories.

- I’m going to skip over these.

Coffee Can

The Coffee Can portfolio is one of the things this book is famous for.

- It’s a popular concept on the UK investment bulletin boards, though in my opinion, most people use it incorrectly.

It all began with Robert Kirby, then a portfolio manager at Capital Group, one of the world’s largest investment-management firms. He first wrote about the coffee-can idea in the fall of 1984 in the Journal of Portfolio Management.

The idea comes from the Old West when people put their valuables in a coffee can (and kept it under the mattress – so it’s a similar idea to keeping your cash under the mattress.

You stick your companies in the metaphorical can and they don’t look at them for 10 years.

- It’s a nice idea, but I don’t think there are many investors like that left these days.

It’s a bit like a venture capital approach – you hope that a couple of big winners will compensate for the inevitable losers.

As an example, Mayer uses the Voya Corporate Leaders Trust Fund.

It bought equal amounts of stock in 30 major US corporations in 1935 and hasn’t picked a new stock since. It still has some of the same names it had in 1935, but it also has positions that came about through mergers and/or spinoffs. The fund has beaten 98 per cent of its peers over the last five- and ten-year periods. It’s beaten the S&P 500 for 40 years.

He also tells the story of the Massachusetts Investors Trust, the world’s first open-ended mutual fund.

- This is a more cautionary tale.

The problem with MIT from Wall Street’s perspective is that nobody could make any money off it – except the investors in the fund. The fee started to go up. By 1969, the fee was up 36-fold while assets under management were up just 7-fold.

The external manager also managed the fund more aggressively and traded more frequently. A sad decline set in. By 2004, Blackrock bought the fund and merged it with others.

Company Lifespan

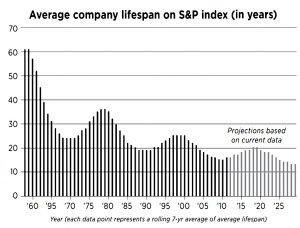

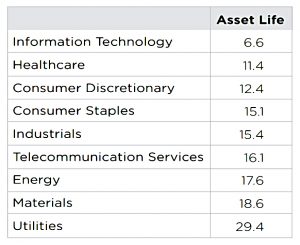

The average lifespan of a firm in the S&P 500 index is now less than 20 years. The average lifespan was 61 years in 1958.

More and more firms are in shorter-asset-life industries. So, 35 years is probably too long a horizon to plan over. This creates some tension with the 100-bagger idea – between holding on and the potentially destructive effect of time.

Big drops

Mayer looks at firms that 100-bagged, but had big drops along the way:

Apple from its IPO in 1980 through 2012 was a 225-bagger. But those who held on had to suffer through a peak-to-trough loss of 80 per cent – twice!

And you would have been holding with no knowledge of the iPod, or iPad, or the iPhone.

Netflix, which has been a 60-bagger since 2002, lost 25 per cent of its value in a single day–four times! On its worst day, it fell 41 per cent. And there was a four-month stretch where it dropped 80 per cent.

Amazon is a similar story.

Optimism

In the next section, Mayer attempts to explain why a coffee-can portfolio need not imply optimism on the part of the holder. We know what Buffett thinks:

[I have] always considered a `bet’ on ever-rising US prosperity to be very close to a sure thing. Indeed, who has ever benefited during the past 238 years by betting against America?

The opposite view comes from Ada Lee:

Unfortunately, that sort of statement is completely true right up to the day it is completely false. One might have said the same thing about Athens right up to the start of the Peloponnesian War, or Rome through the rule of Augustus, or even the Soviet Union up until around 1980.

Mayer quotes Barton Biggs, who wrote a book about preserving wealth during troubled times.

- He recommended 75% stocks.

Stocks were often the best way to preserve purchasing power. [And] the best shot you have at growing your wealth is to own stuff. You want to be an owner. Ownership of assets is your best long-term protection against calamity.

For the other 25%, he suggested a ranch – the survivalist approach.

Let’s think about a coffee can for catastrophists. You could, if you were so inclined, stuff your coffee can with gold. I wouldn’t do that, but the point is the coffee-can idea is not an expression of Buffett-like optimism on America. You could put whatever you want in your coffee can.

The essence of the coffee-can idea is really that it’s a way to protect you against yourself – from the emotions and volatility that make you buy or sell at the wrong times.

This is a good point, but you can achieve the same goal by trading systematically – and on every trading day if you like.

That’s it for today.

- We’ve covered around 20% of the book, so I expect to write another four articles, plus a summary.

The 100-bagger is an intriguing concept, but I have a few questions still to be answered:

- how do we identify likely candidates?

- how do we know when to bail?

- how do we hang on for likely 20 years, during which time the position could grow to 50% of our portfolio?

Until next time.