The Bonfire of the Taxes – IEA Report

Today’s post is about a report from the IEA on tax simplification, which claims that the UK could get rid of more than 20 levies – a veritable bonfire of the taxes.

Contents

Bonfire of the Taxes

A couple of weeks ago the IEA published a fascinating report – they called it a monograph – on taxation. (( OK , I admit, not everyone will find it fascinating ))

- It’s timed to coincide with “a time of great change in the British economy” – I think this means Brexit and a new PM and Chancellor, though I suppose we can now add Trump to the mix.

It’s a long report (230 pages, 70 thousand words) so we won’t have space today to cover everything.

- If you’re in a hurry, there’s also a summary document which is only 32 pages.

With the Autumn Statement looming later this week, our main focus today will be the proposed tax changes, which are radical.

- We’ll revisit the other areas of interest in later posts.

A similar but less ambitious report was published by the Adam Smith institute in July 2016, calling for the end of corporation tax and farming subsidies (but for tradeable fishing quotas and for more immigration of skilled workers).

- We’ll also look at that report in a future post.

A brief history of tax

The IEA report covers (amongst many other things) the history of taxation in the UK and elsewhere.

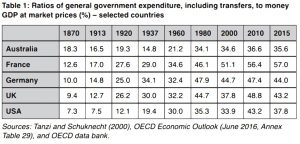

Measuring taxation and government spending as a proportion of national income is not easy, but it’s clear that there is an upward trend in both (as a share of national income) over the past 100 years.

- The UK government spent around 13% of national income at the start of World War 1, but now spends between 40% and 45%.

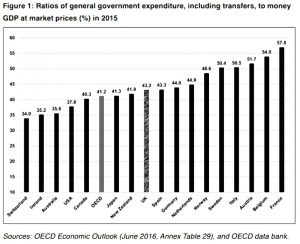

- This is is similar level to say Germany, but higher than many Western countries (Switzerland, Australia, Ireland).

- Welfare payments (which don’t include health or education) have doubled to 14% since the 1960s, whilst government investment has halved to 3% over the same period.

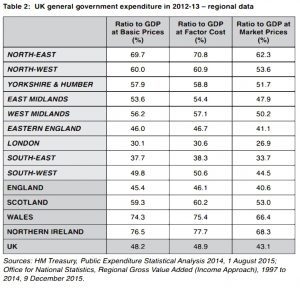

In several UK regions, government spending is between 67% and 75% of GDP.

- By contrast, if London were a country it would have the lowest government spending ratio in the OECD.

Austerity

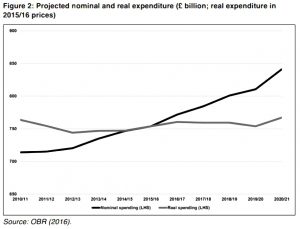

The general public believes that government spending has fallen significantly since the coalition government was elected in 2010, via what the mainstream media call “austerity”.

- In fact, nominal spending went up by 4.6% between 2010 and 2015, and real (after inflation) spending was reduced by just 0.5% a year.

- Since the population increased during this period, real per capita spending decreased by around 1% pa.

Despite this, government spending in 2015 was 45% of GDP.

- Current plans for government spending to 2020 show further nominal increases, a slight increase in real spending, and spending as a share of national income to fall to 41%.

Tax, growth and welfare

The IEA report also studies the relationships between the level of taxation and both GDP growth and citizen welfare (as distinct from welfare payments).

- The report works out the optimum level of taxation to maximise growth, and the higher level that maximises welfare.

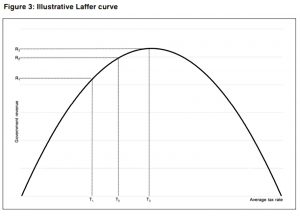

- It also notes the limit we have previously mentioned of how much tax can be sustainably collected (the top of the Laffer curve).

They point out that taxes on mobile capital and income have bigger negative effects than say tax on land, consumption and activities with externalities (pollution etc).

They conclude that 10% of tax / regulation / government spending leads to a 0.8% to 1% reduction in the long-term growth rate, depending on which model is used.

- Thus the 30% increase since World War 1 would produce a growth rate that is 2.4% to 3% lower.

The IEA conclude that the growth-maximising share of government spending is between 18.5% and 23.5% of GDP.

- The welfare-maximising share is between 26.5% and 32.5%.

- The maximum sustainable level (maximum sustainable tax take) is 37% to 38%.

So even by 2020, we will remain above the maximum sustainable level of spending, more than 10% above the welfare optimising level, and some 20% above (or double) the growth-maximising level.

Tax simplification

The report proposes a radical simplification of the tax system in order to collect the optimum amount of tax (20% to 25%).

- This simplification involves getting rid of more than twenty duties – the bonfire of the taxes mentioned in the title.

Corporation tax

The tax change that grabbed the headlines was the abolition of corporation tax, to be replaced by a tax on distributed income (dividends) via income tax and VAT.

- This would raise more revenue and reduce the opportunities for avoidance.

- Corporation tax discourages investment (by lowering the returns on it), which in theory lowers productivity and hence wages.

- It also encourages capital to move to another country (unless you keep your national rate competitively low).

The IEA feels that this reform has been held back by the misunderstanding (they call it a “fiction”) that corporation tax is paid by companies themselves, rather than by the individuals and institutions that own its shares (and to a lesser extent, its workers and customers).

I have no problem with this change in principle, though there could be issues arising from its implementation, assuming that this is done on a unilateral basis, rather than with international cooperation.

Whilst I don’t like multinationals transferring profits from one jurisdiction to another, I’ve never had a problem with a firm that has a large turnover but low profits.

- Excluding transfer pricing, this is usually because of high staff costs or lots of re-investment in the business, both of which are fine.

- Paying high salaries will still lead to tax hitting the UK government, albeit through a different route.

Given public contempt for multinationals, and the political gains available, it’s likely that some change to corporation tax is coming.

- But this is more likely to be a switch to assessment on the basis of assets, staff and sales (customer location) than abolition.

- This in turn could lead to companies withdrawing from high-tax countries.

The rest

The other taxes that the IEA want to get rid of include:

- national insurance

- capital gains tax

- inheritance tax

- council tax

- business rates

- stamp duty

- the TV licence

- excise duty on alcohol and tobacco

- vehicle excise duty (road tax)

- air passenger duty

- the apprenticeship levy

The replacements

The IEA’s new system has just five taxes, designed to reduce tax as a share of national output to somewhere between 20% and 25%.

- income tax would be a flat rate of 15% on incomes above a £10K allowance, and on all distributed profits (dividends)

- VAT would be reduced to 12.5%

- a new housing consumption tax of 12.5% (based on rents and imputed rents) would be introduced

- a location land value “designed to capture and average of 75% of the location value of land ownership” (I’ve no idea how this would be calculated)

- a fuel duty at half the current rate

The effects

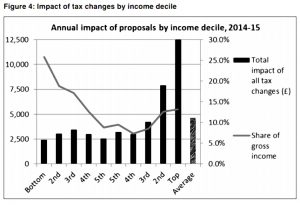

As might be expected, the richest 10% of the population see big increases in their incomes from these changes, but the IEA says that those on lower incomes would gain more (in percentage terms).

The chart below shows the changes by decile in pounds as well as percentages:

Conclusions

- Government expenditure around the world has risen significantly over the past over the past 100 years.

- In the UK, it’s gone up from 13% to around 45%

- Since the 1960s, welfare spending has doubled to 14% and government investment has halved to 3%

- The optimal level of government spending for growth is around 21% of GDP

- The optimal level of government spending for welfare is around 30% of GDP

- The maximum tax take (and hence maximum sustainable government spend) is around 38% of GDP.

- Even by 2020, the UK will still be spending more than this.

- The current system could be replaced by a five tax system designed to raise no more than 25% of GDP.

- This would increase incomes for all income deciles, particularly the poorest.

I’m not a fan of big government, so a lot of this report makes sense to me.

- In this regard I’m a classic liberal – I think that I know best what to do with my money

My big concern with the plan that the IEA have put forward is about the land tax.

- I can’t find out how this would be calculated – it’s surprising to me that in a 250-page report they couldn’t find space to explain this a bit more.

Given the extreme variation in land values across the UK (my house is worth twenty times more than the one that I grew up in) there’s the potential for a lot of disruption.

- Implementation would have to be carefully handled, and presumably quite gradual.

Swapping council tax for a housing consumption tax also sounds risky, but a back of the envelope calculation suggests that although there would be big changes, they might not be catastrophic:

- my council tax is currently around £2K annually

- renting my house would cost between £40K and £45K a year (( I couldn’t find a house in the surrounding streets for rent, but those on adjacent sides of the common are renting for this much ))

- so presumably my new tax bill would be 12.5% of that, or £5K to £5.6K

That’s quite a hike, though presumably some of the other tax reductions (income tax and VAT, mainly) would compensate.

I really wish we could simplify the UK’s tax system, and significantly reduce government spending, but given Brexit, it’s unlikely to be on anyone’s agenda for the next five years.

- I’m pretty sure that Philip Hammond won’t be abolishing too many taxes in this week’s Autumn Statement, but we can only hope.

Until next time.