Coronavirus Numbers

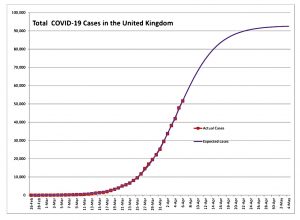

Today’s post is a look at the coronavirus numbers we have, and at what they might mean.

Contents

The Questions

I’ve been putting off writing this article in the hope that the data will become clearer.

- That hasn’t really happened, and in the absence of that clarity, a lot of misinformation – often politically motivated – is circulating.

Here are some of the questions I’d like to look at today:

- How contagious is the virus?

- How deadly is the virus?

- How many excess deaths should we expect?

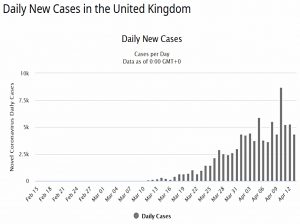

- How prevalent is the virus, particularly here in the UK?

- When will we have an adequate testing regime?

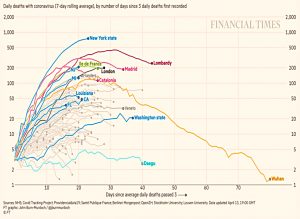

- What is the likely path of the pandemic in the UK?

- When might we have a vaccine?

- What are the exit strategies from the current lockdown?

- Can we trade lives against economic loss?

Many of these issues are closely related, with definitive answers to one issue requiring greater clarity on another.

- Before we start, here’s the usual disclaimer that I’m not a doctor, or an epidemiologist – I’m just someone who likes to analyse data.

Contagion

The key number here is the R0 – the number of people that a single sick person is likely to infect.

- Anything bigger than 1 is bad news.

This ought to be the simplest question to answer, but even here there are several complications:

- It seems that around 50% of those infected show no symptoms – these patients will not present to the health system

- This comes from decent testing on evacuees from Wuhan city, the Italian town of Vo and in Iceland.

- People can be infectious while they are showing no symptoms, and indeed some younger people with no symptoms have been described as “super-spreaders”

- The incubation period is not known and could be two days or more than two weeks

- Around 80% of those who do show symptoms have a mild form of the disease – these people might stay home, too

- The symptoms associated with the disease are quite varied (with fever and cough being most common initially, followed by breathing difficulties in the most serious cases)

- Many of the common symptoms are similar to other respiratory infections prevalent in the northern hemisphere at this time of year (colds, flu, hayfever)

- Few countries have been able to carry out the necessary levels of testing to establish definitively how many people have the virus

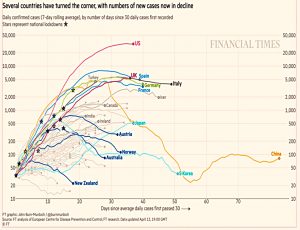

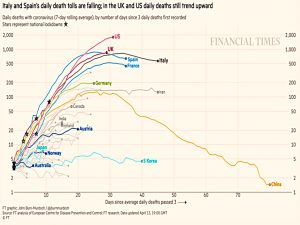

- Testing regimes differ between countries, making read-across from territories further into the pandemic cycle difficult

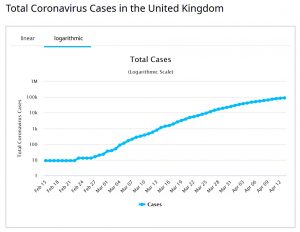

What we can say is that it seems to be contagious enough – lots of people are infected (1.9M globally as I write this).

- Covid seems to have an R0 of 3 or more.

At the same time, there is some evidence that the virus is quite hard to catch.

- There are clusters of infection where people are cloistered together.

- And lots of cases where people might have repeated exposure (particularly in the healthcare system, but also in transport eg. buses).

- A comparison between Lombardy (65% hospitalisation) and Veneto (20%) suggests that hospitals might be hubs for infection.

- And countries with looser responses (eg. Sweden) are not showing a marked increase in infections (yet?)

Perhaps a better way of putting it is that we don’t know exactly how the virus is transmitted – and because of that, exactly what measures will prevent infection.

- Handwashing certainly seems to help (though I’m surprised by the demand for antibacterial gels to combat a virus).

- And the greater use of masks in Asia may be a factor in the apparently lower death rates.

But is six feet of separation enough, or is it ten metres?

- And how long does the virus survive on shopping trolley handles or on banknotes?

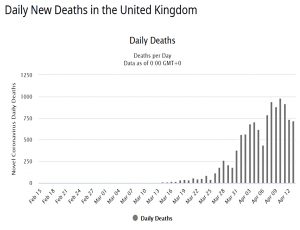

Deadliness

This ought to be the easiest question to answer since deaths are well recorded.

But:

- Some countries count dying with Covid as well as dying from Covid.

- Some countries record only hospital deaths, and not those at home or in nursing homes.

- Deaths are (at least initially) often logged against the day of reporting rather than the day of death, adding noise to the data.

- Death rates vary significantly by age, gender and pre-existing health conditions (sick old men do worst) – and possibly by other demographic variables.

- Crucially, without knowing the infection rate, we don’t have the denominator for our calculation.

Early fatality calculations came out at around 4%, but more testing suggests that the real rate might be only 10% of that.

- And of course, the fatality rate varies massively between sub-groups of the population.

It also varies between countries.

- As I write, German deaths are 36 per million (with 16K of that million tested) and UK deaths are 156 per million (with 5K tested) – yet Germany has 25% more cases per capita.

Here in the UK, according to retired pathology professor John Lee in the Spectator:

We don’t really test for flu, or other seasonal infections. If the patient has, say, cancer, motor neurone disease or another serious disease, this will be recorded as the cause of death. This means UK certifications normally under-record deaths due to respiratory infections.

Since the emergence of Covid-19, the list of notifiable diseases has been updated. Every positive test for Covid-19 must be notified, in a way that it just would not be for flu or most other infections. If any of these patients dies, staff will have to record the Covid-19 designation on the death certificate.

So the way deaths are recorded will inflate the apparent deadliness of the virus.

Excess deaths

We won’t really know how deadly the virus is until the pandemic is over.

- Around 600K people die each year in the UK, and the true impact is any excess deaths over this figure.

And even that is only a net impact.

Some of the trade-offs include:

- People (usually old and sick) who would have died anyway, many of them from a regular winter flu.

- People who won’t die from other contagious diseases that they won’t catch because of the lockdown.

- Varying accident rates in the home (up), the workplace (down) and the roads (down).

There are also second-order effects like increases in poverty, substance abuse, domestic violence and mental health issues – each of which would impact society’s goal of long and healthy lives.

- And people with “normal” diseases may not seek help, or may no longer be offered it.

So far there is little evidence of an excess death rate in any country – but from the discussion above, perhaps we shouldn’t expect it.

- The ONS has reported that the 16K deaths in the week to 3rd April was a record for this time of year (since flu is usually receding by now) – but only half of the extra 6K deaths were attributed to the cornoavirus.

It will take some time before we can get to the bottom of this one.

Prevalence

So far, the numbers of deaths are thus consistent with more than one scenario:

- Rare and deadly

- Common and not lethal to many

This explains the Oxford study of the virus spread which pushes a “tip-of-the-iceberg” theory – most infections are undetected due to limited testing and lack of symptoms.

- Which in turn has implications for the requirement for lockdowns (see below).

Testing

There are two types of test:

- Antigens – answers whether you have the virus today

- Some countries are using facial temperatures (measured using something like an infra-red camera) to do instant tests

- Antibodies – answers whether you have already had Covid (and might therefore now be immune)

We don’t seem to have nearly enough of the first test.

- And we have almost none of the second (at least, of versions that work reliably)

One of these tests can be processed quickly, and the other is slow.

- Since I can’t access either this is of no consequence presently.

Ordinary people (ie. non-royals or government ministers) can only get a test if they are sick enough to need to go into hospital.

- It’s a gatekeeping device to gain access to a bed.

Even most of the front-line health professionals haven’t been tested yet.

Herd immunity

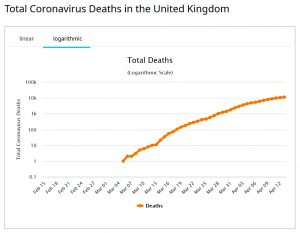

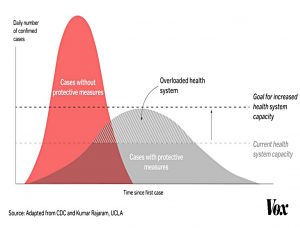

By now everyone will have seen the “squash the sombrero” graphic.

- The idea here is that the spread of the disease is slowed down – through social distancing and lockdown.

- It’s not that the total number of cases is reduced, they are just spread over a greater period of time.

- This means that the peak rate of infection is lowered so that hospitals and ICUs are not swamped.

- Simultaneously, the capacity of the health system is increased (eg. the new London Nightingale hospital at the Excel centre) to avoid people “choking to death in corridors”.

But whether we squash or not, the virus will make its way eventually through the entire population until we have herd immunity.

- This happens when around 60% (67%?) of the population have had the virus, and so the effective R0 falls below one.

- At this point, the number of cases will fall even without lockdown.

Herd immunity can be achieved either naturally (through a lot of infections) or via a vaccine.

- Two versions of the path to herd immunity include a single large wave of infections in 2020.

Or a smaller wave in 2020 (perhaps because the virus dies off in the summer, like many similar infections) leading to a resurgence in the winter of 2020/21.

Vaccine

The good news is that there is an unprecedented human effort towards creating a vaccine.

- The bad news is that we don’t have a good track record in creating vaccines in double-quick time.

There’s still no vaccine for AIDS after 30 years, nor one for Hepatitis-C.

Most observers seem to think that a vaccine might be available by the end of summer 2021, in time to prevent a third wave of infections in winter 2021/22.

- I think that making billions of doses of a vaccine available on that timescale would be a remarkable achievement.

Lockdown exits

In the absence of a vaccine, there are two key influencers of the path out of lockdown:

- Widely-available testing

- Antibody testing is preferable, allowing the now-immune to return to work

- Antigen testing is part of the second factor, below

- Pervasive monitoring

- Apple and Google are collaborating on modifications to their phone operating systems to allow automatic logging of personal contacts using Bluetooth

- This data will be posted to a central database nominally owned by a trusted authority (presumably the NHS in the UK)

- Contacts will be matched to a database of those who have tested positive, allowing anonymous alerts

There are obviously privacy concerns with the monitoring regime, but these will no doubt be overcome in time of “war”.

- It’s also possible that any return to normal will be phased in by age and/or geography (for example in the UK London is a couple of weeks ahead of the rest of the country).

At least here in the UK we have the luxury of watching other European countries attempt to end their lockdown a few weeks before we need to.

- Austria has just re-opened small shops and garden centres.

- Italy and Spain have also begun to relax their lockdown measures.

Economic trade-offs

There is little doubt that a six-month lockdown would inflict a lot of economic damage.

- Thousands of businesses and millions of jobs would be lost.

And a poorer country would be less able to afford improved healthcare.

At the individual level, the pandemic has raised the topic of how much money society should spend on keeping people alive.

- The UK stimulus package announced so far is around 250% of the annual NHS budget, which is serious money (though much of it is structured as loans, and it actually plays out as a transfer from current and future taxpayers to those who lose current work, rather than an absolute cost).

Economics is at its heart about resource allocation – since resources (including money) are not limitless, how are they best allocated?

- Here in the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (with the 1984-style acronym of NICE) decides what we spend the NHC cash on.

The cost-benefit analysis is based around the Quality-Adjusted Life Year or QALY.

I object to this measure as:

- it obviously discriminates against old people, who cannot be expected to live as long as youngsters, and

- it assumes that a healthy year for every person has the same value.

We aren’t born equal, and we don’t become equal.

- If anything, we become less equal through life, as we either take advantage of – or squander – the opportunities that we are presented with.

Even for an individual, one year is not the same as the next.

- The first 25 years of my life were of little value to me in comparison to the next twenty, and the fifteen since then have been even more worthwhile.

In a free society, (richer) individuals could work around the ageist maths of this oversimplification through access to private medicine.

- But as we have seen this year, in a real crisis, all medicine will be socialised.

Back to QALY – people with pre-existing (physical) conditions have their years downgraded to a lower value.

- On his website, Dr Malcom Kendrick uses the example of someone with hip pain (50% quality of life) gaining 20 years of pain-free life from a hip replacement – that’s 20*50% = 10 QALYs.

Before the pandemic, NICE supported interventions costing less than £30K per QALY. (( The Treasury actually uses a £60K figure for a QALY, but NICE doesn’t think that the NHS can afford to spend that much ))

- That equates to 11.7M QALYs for the £350 bn of stimulus.

Given the likely excess death numbers and the age profile (and therefore pre-existing quality of life) of those who will die, that’s a hard target to reach.

- Kendrick gets to around 1M QALYs in his simplest calculation, but I expect it will be much less in reality.

- I suspect more like 100K – 200K net QALY, but it’s possible that a non-lockdown scenario with a flooded healthcare system could have had an impact of perhaps even 10M QALY.

So I accept Kendrick’s argument, but I’m still uncomfortable with relaxing a lockdown that protects a particular sub-section of the population.

- We’ll never reach widespread agreement on which sub-sections are worth spending unlimited amounts of money to preserve.

Conclusions

I’m slightly disappointed that three months into what looked like promising data collection, we don’t know enough about the virus to make useful predictions.

- One thing that needs to happen after the pandemic is over is the introduction of international standards on data collection and in particular the recording and attribution of deaths.

It might be that we will look back on the lockdown as a massive overreaction (like the response to the 2001 foot and mouth epidemic), but it’s easy to understand why during the fog of war, the government would prefer to err on the side of caution.

It’s also hard to visualise the world six or eighteen months from now, but I expect some behaviours to change, at least until we have a vaccine (or a reliable treatment).

- I’m similar enough in age and build to Boris to realise that I don’t want to catch this thing – it may have similarities with flu, but the experience for a lot of people is much worse.

Which means I won’t be rushing back to restaurants or crowded bars or probably even to live sports events (football).

- Turning to investment just for a moment, this potential change has implications for any business that needs people to congregate.

Eighteen months is a long time to survive with severely impacted revenues.

- Until next time.

Perhaps we should leave these musings to the experts – but I understand and have often succumbed to the temptation. For a variety of reasons, I find the contrast between the numbers for UK & Germany particularly puzzling.

Also, I too am no expert, so could easily be wrong.

However, I think you need to tidy up the testing sections – e.g. use of “quick” & “slow” may be wrong way round and description of antigen test should include “Covid”.

Herd Immunity Threshold (HIT) for R0 of 3.0 is c. 67%.

I believe that a HIT of 60% in consistent with an R0 of 2.5.

IIRC your background is physical sciences (PS) – as is mine.

IMO the level of scientific discipline associated PS is rarely present/possible with medicine.

I don’t think there are any experts at the moment. If anyone really does understand, they aren’t going to risk telling us, since the MSM is clearly not onside.

I’m not too interested in the details – I just wanted to work my way through a lot of conflicting/bogus information to figure out where we stand. R0s and HITs are less important than testing, treatment and a vaccine. I’m after a time scale for any return to normality and some predictions for what a “new normal” might look like – this remains primarily an investing site.

Telegraph is reporting this morning that under-40s don’t develop antigens/immunity, which is not good.

Re: the role/behaviour of the MSM – do not get me started!

Thanks for setting out your thoughts. IMO, the big unknowns are (a) whether the virus will return in a second or third wave (as did Spanish flu), (b) whether social distancing plus mask wearing in public will be sufficient to keep the infection rate under control if it does re-appear and (c) whether and when a reliable vaccine will appear.

I, too, would like to understand the reasons why the German death rate per million appears to be or is so much lower than ours and Italy. John Lee (the recently retired pathology professor to whom you referred) suspects that there is a systematic issue at work (such as different death allocation criteria).

According to my understanding of the Imperial College (IC) modelling, it is because there are a lot less people infected in Germany – and it just so happens that Germany are detecting more of them as they are doing more tests. For more details, compare:

https://mrc-ide.github.io/covid19estimates/#/details/United_Kingdom and

https://mrc-ide.github.io/covid19estimates/#/details/Germany

Whilst I understand (at a high level) this theory/model I am struggling to understand why the infection rate would be so much lower in Germany than neighbouring countries, such as France and Italy