Weekly Roundup, 23rd August 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about Santander cutting the interest rate on its current account.

Contents

Cash interest

Naomi Rovnick and Emma Dunkley looked at the decision by the bank to cut the rate on its current account from 3% (hence the 123 branding) down to 1.5%. ((It’s an unusual Chart story this week because the online article is actually missing the chart – We aren’t missing much: it simply showed the annual interest on £5K, £10K, and £20K before and after the cut, with a “best buy” 2-yr bond for comparison ))

A lot of the UK finance blogs have been writing about this change, and it’s been discussed a fair bit on Reddit as well.

- I must admit to being a bit stumped by all the fuss.

- I hold about 15% of my net worth in cash, so you’d think I would be more concerned.

But cash isn’t about returns, it’s about security.

- I hold cash mainly so that I have money for several years of living expenses.

- I don’t want to have to sell stocks during a bear market.

You have to hold risk assets (mainly stocks) to reach financial independence.

The Santander account tops out at £20K, so the annual interest was £540 (after a £60 fee).

- Neither the 20K maximum investment nor the £500 return would have much impact on your lifetime’s financial plan.

Whether I get 3% or 1.5% on my cash – or as on many of my accounts, 0% – isn’t really a big deal, particularly with the recent low inflation.

- As long as the money is still there when I need it, it has done its job.

Given the government’s underwriting of the first £75K of cash held with each banking group, that’s really the only bit you have to get right.

- Make sure you split your cash into £75K chunks and you can’t run into too many problems.

If inflation picks up, I might look at putting some of the cash to work returning a yield.

- But I’ll always need 5% to 10% in cash to get me through a bear market.

Love of money

John Authers looked at the love of money, and whether it is good for your wealth. ((This is the second FT article this week where the chart from the printed paper is not part of the online article – I hope this is a temporary glitch ))

State Street has used Thomas Li-Ping Tang’s Money Ethic Scale from 1992 to rank investors in 20 countries according to how greedy they are.

- The quiz tries to find out how important money is to a person’s self-esteem.

- It also asks them how they would respond in a variety of situations.

The bad news for the greedy is that the more emotionally attached you are to money, the more likely you are to make mistakes with it.

- The greedy were more likely to buy at the top and sell at the bottom.

- They had shorter time horizons and traded more (incurring more commissions).

They also believed that they could wait until later in life to save for retirement, and indeed they saved less for the future.

- Those less attached to money were more likely to save regularly.

- Some support for workplace pensions auto-enrolment, then.

Looked at by country, developing nations (India, China, Mexico) were greediest, with richer countries (Switzerland, Holland, Australia, Sweden and the UK) the least greedy.

- There is just one anomaly from this rule: the US, despite being rich and religious, is also very greedy.

- Cue jokes about which faith the Pope has, and what bears get up to in the woods.

Shopping boom and business gloom

Still in the FT, Emily Cadman look at the contrast between consumers and businesses in their reaction to the Brexit vote in June. ((This is another FT article with missing charts – something is definitely wrong this week ))

Consumer spending – which accounts for 60% of UK GDP – was up in July, with the annual rate of increase reaching a 10-month high.

- But the Markit/CIPS survey of business activity had its biggest fall since 2009.

- The Recruitment and Employment Confederation also reported permanent hiring falling to 2009 levels.

Consumers are thought to react mainly to the state of their own job, and to prices in the shops.

- Since there have been no lay-offs, and inflation has yet to bite, they so far have no reason to worry.

- Manufacturers have already been hit by increases in the cost of oil, metals and other supplies.

Consumers and companies views will have to merge in the medium-term, as the picture becomes clearer, but it looks as though we’ll have to wait a bit longer to see which of them is right.

The endowment effect

Over in The Economist, Buttonwood looked at the endowment effect – the fact that we value things that we already own more than other people would.

- In the classic experiment, students randomly given a mug would only part with it for $5.78.

- Those not given a mug would only pay $2.21 for one.

Similarly, when asked whether they preferred a mug or a bar of chocolate, the split was 56:44.

- When the two items were randomly allocated, 90% preferred to stick with what they were given.

A new paper looks at the endowment effect in the Indian IPO market.

- Over-subscribed IPOs are often allocated by lottery, so some investors have shares when trading begins and others would need to buy in the open market.

A month later, 62% of those allocated the shares were still holding them.

- But only 1% of the “losers” had bothered to buy them.

Since IPOs tend to rise on the first day (by an average of 52% in India), this could be the explanation.

- But there was no correlation between the size of the first-day premium (or discount) and the number of “losers” who bought.

- And in any case, a strange escrow system used in India means that gains are small in relation to the cash you need to put up (an average of $62 on $1750, or less than 4%).

There’s evidence for the endowment effect on the way back down, too.

- After one year, the average IPO has lost 54%.

- So the first-day “winners” should sell.

- Yet 46% still held after a year, and only 1.7% of losers had bought in.

The paper’s authors rule out inertia, as the effect persists within the group of investors who trade more than 20 times in the month of the IPO.

- Similarly, even experienced investors – who had taken part in more than 30 IPOs – were still four times more likely than “losers” to hold shares at the end of the first month.

So remember not to get too attached to your favourite shares.

- It won’t help you in the long run.

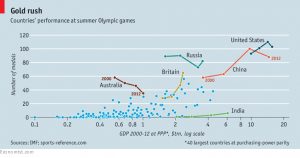

Olympic success

The Economist also looked at Britain’s success in the Rio Olympics.

- Team GB finished second behind only the US, and became the first country to increase its medal total immediately after hosting the games.

Apart from the warm glow, this is also interesting as potential evidence that state intervention can work.

- Should the government in fact be poking its nose into manufacturing (as Theresa May has implied with the creation of a Department for Industrial Strategy)?

In the first place, it helps to be a rich country.

- China’s medal count has increased along with its GDP per person.

Population also helps, and combining the two means that absolute GDP is a good predictor of medals.

- That would give Team GB a target of 5th or 6th place.

- It also makes Russia’s out-performance – perhaps because of doping – stand out.

A lot of the improvement by Team GB since a dismal showing in Atlanta in 1996 is down to increased funding (from the National Lottery).

- Team GB received £350M in the four years up to the Rio games.

But it also has to be spent wisely.

- Britain focuses on sports where it is likely to win medals.

- This could be through tradition, neglect by other nations or just the fact that there are many sub-disciplines and therefore lots of medals to be won.

Cycling, rowing and sailing are most preferred.

- Weightlifting, fencing, archery and volleyball have all suffered in comparison.

- Gymnastics is a good example of a sport where Britain used to be poor, but showed promise in 2012, received more investment, and won its first two golds in Rio.

The same principles are applied at an individual level, with potential medal-winners better supported than also-rans.

- Athletes whose fortunes change can be ruthlessly cut from the programme.

Translating this approach for industry is not straightforward.

- To begin with, there aren’t just three spots on the podium, and your position in international industry league tables is not crucial.

- The important thing is that money is well-spent, and produces a return.

- And basic infrastructure that helps many industries could be a better investment.

But it’s clear that performance metrics are important.

- Public sector league tables, and performance related pay are the way to go.

- Not everyone who works in the NHS is a saint.

And we need to play to our strengths:

- We’re good at financial services, media, and higher education and specialised manufacturing.

- We need to stop pretending that we that we can make steel cheaply enough.

Until next time.