Weekly Roundup, 14th April 2020

Today’s Weekly Roundup tries hard to largely steer clear of the coronavirus for a change.

Contents

Redwood fund

In the FT, John Redwood was able to reassure us that he has repositioned his ETF portfolio to get through the crash.

- He’s now 30% in cash and 30% in government bonds – 40% is his self-imposed minimum exposure to stocks.

He was down 9% on April 7th, which is not bad compared to 24% for the FTSE All-Share.

- My own multi-asset portfolio is down a little less than 7% for the year – it holds slightly fewer bonds and stocks and a lot less cash to achieve a similar result.

John has no exposure to the Eurozone or to China, and is overweight the US and tech.

- I am still globally diversified, with my biggest underweights (against my own targets, not global market cap) in the UK and Europe.

Re-distribution

Merryn Somerset Webb warned that there is radical wealth redistribution ahead.

Interest rates are going to stay low. Rents might well fall. Taxes are bound to go up on those with unearned income. If manufacturers are no longer able or willing regularly to outsource all production to cheap places abroad, labour’s share of returns will surely rise.

[Reasearch from ] the San Francisco Federal Reserve on previous European pandemics suggests that interest rates have historically fallen for 20 years afterwards and real wages have risen for 30 years.

She even forsees debt jubilees.

- She recommends diverse sources of income (including Japan, it will come as no surprise to hear) and also hanging on to your ability to earn.

Which is a lot easier to do if you are young.

Price gouging

The Economist argued that bad morals outweigh good economics in the case of price gouging, or as the newspaper called it, disaster profiteering.

There are two arguments in favour of increasing the price of goods in short supply:

- In the short term, high prices ensure that goods go to those who need/want them the most (or at least those who are willing to pay more for them) rather than just the people who were in the right place at the right time.

- In the medium term, the high prices serve as a signal for suppliers to increase production – diverting capacity from products less in demand – because there are excess profits to be made.

Left-wingers would argue that only allocation via a central authority is “fair”, since having a disproportionate ability to pay is “unfair”, even if it is the result of earlier prudent actions.

- But a quick look at history can show how those ideas work out.

The Economist focuses on face masks, which are surprisingly complicated to make.

- When only China needed more masks, local firms quite rationally looked for masks abroad rather than invest in the extra capacity that might only be needed for a short time.

- It took government subsidies to increase production.

But price gouging usually occurs when extra supplies can’t be easily sourced.

- And masks are an unusual case, being of far more benefit to front line health workers than to the general public.

The real shortages in my part of town have been toilet roll, hand sanitiser, pasta and tinned goods.

- Higher prices for these in the early part of the panic would have helped preserve supplies for longer.

And the rationing and queuing (supply choking) which was the actual response to shortages simply meant that people went shopping more frequently and to a wider variety of shops.

- Which must have increased their chances of being exposed to the virus.

More generally, if we want people to behave prudently, we need to reassure them that good behaviour will count for something in a crisis.

- Reallocating resources to the reckless will encourage us all to be reckless next time.

Unicorns

The Economist also thinks that lots of startups will come to regret their unicorn status (a $1bn valuation before a public listing).

- After multiple funding rounds, they have a lot of debt or quasi-debt.

By coincidence, I’m currently reading Secrets of Sand Hill Road by Scott Kupor, which explains how the VC process works.

- Scott is a partner at Andreessen Horowitz, perhaps the best known Silicon Valley VC (the firm is also known as a16z, and Sand Hill Road is where the main VCs are based).

When VCs invest in a startup, they get convertible preferred stock (convertible to common stock on an IPO or a takeover), which means that the quoted “post-money” valuation is inflated.

- Preferred stock is repaid first, so on a low sale valuation, the VCs receive a disproportionate amount of the money.

The idea behind this is to incentivise the founder to hold out for a high sale price.

Say the VC invests $20M for 20% – a post-money valuation of $100M.

- If the firm were sold for $20M, all of the money would go to the VC, for a break-even exit.

If they held common stock, they would take an 80% loss (and the founder would pocket $16M rather than nothing).

In the second round of funding, VC2 might pay $200M for another 20%, leading to the unicorn $1bn valuation.

- But VC2 insists on a 2x “liquidation preference” – they get the first $400M of any exit.

Add the $20M of VC1, and the founder needs to sell for at least $421M before he makes any money.

In a bear market, [the founder’s] stake is probably worthless. So why not blow the company’s remaining cash on perks, take undue business risks (“gamble for redemption”) or simply give up? He may use his voting rights to stymie an exit for other investors.

We should soon find out.

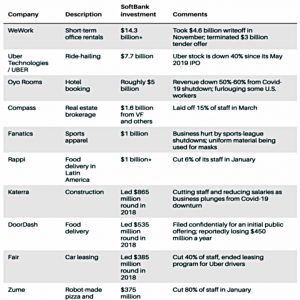

As a reminder of the risks involved in VC, Howard Linzon pointed me at the table above which shows a selection of the SoftBank Vision fund’s misses.

- It’s by no means exhaustive – the $250M+ investment in the dog-walking app Wag is missing, for example.

Special drawing rights

The Economist also asked whether the IMF should handout more “special drawing rights” (SDRs).

- This is a financial instrument from the 1960s based on a currency basket worth $1.36 at the moment.

They can be exchanged for hard cash at an interest rate of 0.05%

SDRs were intended to reduce the world’s dependence on dollars, at a time when most currencies were linked to the US currency (which in turn was backed by gold).

When too few dollars circulated in the world economy, perhaps as a result of America spending less on imports, countries would hoard greenbacks to defend their pegs, and global commerce ground to a halt.

Rather than print more dollars and risk weakening its exchange rate to gold, an alternative reserve asset was created.

After the dollar link to gold was severed in 1971, the idea faded.

- SDRs make up 3% of non-gold reserves, whereas the dollar is more than 50% of them.

Poor countries would like the IMF to issue another $4 trn of SDRs, but the US is not keen – it wants handouts to come with more strings attached.

- And why should we expect them to favour an instrument designed to undermine the dollar?

Keynes proposed bancor [an SDR precursor] just after sterling lost its sway. It might take the emergence of a serious challenger to the dollar’s crown before America sees the appeal of the SDR.

Since an 85% vote is needed, the US (with a 16.5% share of the IMF) has a veto.

SDRs are issued in proportion to IMF contributions, which means that most would go to rich countries in any case.

SDRs do not have to be used to be useful. Their very presence on balance-sheets frees up dollars. And the share of a $500bn issuance flowing to the likes of Liberia or South Sudan would be worth 7-8% of GDP.

But I can’t see Trump going for this.

Robinhood

Robinhood, the low-cost broker we looked at a few weeks ago, has pulled its planned UK launch.

- Their US operations had some damaging outages during the recent market crash, though of course, the firm has denied that either this or the virus are linked to the UK delay.

Since our review, I have discovered Trading 212.

- Between that and Freetrade – and given the stripped-back product that Robinhood had planned to launch in the UK, I think this part of the market is reasonably well covered without them.

RPI

In FT Adviser, Amy Austin wrote about how the switch from RPI to CPI will hit pensions.

RPI generally runs at about 1 percentage point higher than CPI and is currently 2.5

per cent, compared to a CPI of 1.7 per cent.

These are small differences, but they mount up over time.

A saver aged 65 in 2020 could receive up to 21% less per year from his DB pension

by the age of 90.

The change is not yet scheduled, but the period between 2025 and 2030 has been targeted.

- There’s not much we can do about the loss of RPI – but we can minimise our own costs and taxes, which will have a similar (but opposite) effect.

Quick links

I have twelve for you this week, six of which are from The Economist:

- Schumpeter said that the idea that some industries are too important to leave to markets is back on the agenda

- A briefing looked at the changes that Covid-19 is forcing on business

- A leader also covered the changes for the world of commerce

- And another warned that bail-outs are inevitable and toxic

- Article number five looked at the inferior handouts in emerging markets

- And the sixth warned that technology startups are headed for a fall

- UK Value Investor provided a dividend investor’s guide to recessions, depressions and pandemics

- Alpha Architect looked at Volatility, Risk Management and Market Chaos

- And at Daily vs Monthly Trend-following rules

- Pragmatic Capitalism reassured us that this isn’t the next great depression

- Musings on Markets had part 6 of the Market Meltdown series – the Price of Risk

- And Klement on Investing explained that it’s easy to delegate to Robo-Advisors because algorithms are easy to blame when things go wrong.

Until next time.

It will be interesting to see if Tom McPhail’s description of the latest RPI wheeze as being “a bit of “Alison in Wonderland logic” gains any traction.