Weekly Roundup, 20th April 2020

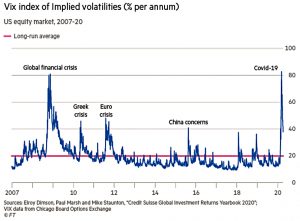

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with The Chart That Tells a Story. This week it was about the VIX.

Contents

VIX

Madison Derbyshire reported that the March 16 peak in the VIx index was higher than any reading during the 2008 financial crisis.

- The fear gauge hit 82.7 last month, against a long-run average reading of 19.7

Normally, half of the excess volatility disappears within two weeks.

- And the VIX is already back below 40.

It usually takes four months (87 trading days) for the VIX to get back to normal.

- But since this crisis involves restarting parts of the economy in sequence, things may take a bit longer this time.

Stick to the plan

Jason Butler warned against letting the virus derail your financial plans.

Now is the time to take steps to improve your relationship with money and the role it plays in your life with a view to seeking a happier, more fulfilled existence.

When something like coronavirus comes along, it shows up the weaknesses and flaws in our relationship with money and our past financial decisions. Having our financial weaknesses exposed like this can evoke strong negative emotions such as shame, guilt, embarrassment and even anger.

The most important thing that we can all do is to learn from our past poor financial choices. Be clear what your future ideal lifestyle looks like — and the role of money in achieving it.

Premium bonds

Leke Oso Alabi reported that the planned cut to premium bond prizes has been cancelled (or more likely, postponed).

- The prize pool remains at 1.4% pa, rather than dropping to 1.3%

This is tax-free – unbeatable for total security and “instant” access if you are a higher-rate tax-payer.

- But you can only hold £50K per person, at which level you would expect to win two prizes per month.

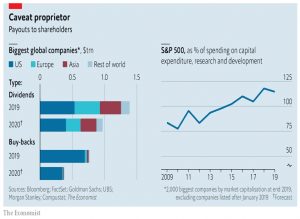

Dividends

The Economist looked at which firms should pay dividends during a pandemic.

[Dividends] get a bad rap from those who think plutocratic shareholders are the outsized beneficiaries of modern capitalism.

But retirement schemes depend on a steady stream of income to honour their commitments; they may instead have to sell shares at exactly the wrong time, during a stockmarket slump.

And when mature or cash-rich companies distribute excess cash it can be recycled into funding young companies or to firms whose balance-sheets need repair.

Payouts are likely to drop by at least 30% this year.

The newspaper sorts companies into three groups:

- Systemically important firms (likely to receive a government bailout, eg. airlines or not eg. banks), who should be required to cut payouts

- Those who need to pay dividends as a signal, and may rack up debts to do so (oil companies are the obvious example) – they should think twice

- Firms with strong balance sheets that are operating close to capacity (tech and utilities) – they should pay dividends to maintain pensioner income (which can, in turn, be recycled into shoring up the damaged balance sheets of weaker firms

EM stocks

Buttonwood made the case for emerging market stocks.

- Market crises are not usually good for EMs.

When there was a mad scramble for cash, the cash everyone wanted was dollars. When the dollar gets bid up, it hurts emerging markets. If inflation returns, meanwhile, it will surely show up first in the developing world.

But of course, for diversification, you need something that behaves differently than the core of your portfolio (which for most of us is developed-economy shares, with a bias to the UK, US, or both).

- Many people will also hold a lot of bonds, including US Treasuries, which further ups their dollar exposure.

So the anti-dollar trade (EMs, but I would argue also gold) remains a good diversifier.

Emerging-market shares look very cheap relative to both their history and to America’s S&P 500 index. Emerging-market currencies are as cheap in real terms as they have been since the mid-2000s.

The only problem is looming inflation.

- If this picks up in EMs first, then EM currencies would fall in order to keep the exchange rate constant in real terms.

Indeed, some asset managers define an EM as a country forced to raise interest rates to counter inflation.

- Asian EMs (Taiwan, South Korea, China) can probably handle this better than Latin America or Turkey.

Inflation

The Economist also looked at the possible return of inflation, which had appeared to have been consigned to the 1970s and 1980s.

Inflation is the result of too much money chasing too few goods.

We clearly have fewer goods and services available a present, and there is a lot of money heading down the pipeline.

- But at present, the crash in demand from broke and locked-down households (particularly on travel and hospitality) means that deflation is a bigger risk than inflation.

If supply chain break and we get real shortages in shops (rather than panic-buying) there will be localised inflation.

- I’m certainly paying a lot more in supermarkets and corner shops than I was a couple of months ago.

- And we can expect medical supplies to be more expensive at present.

But in the longer term, the virus may also lead to structural changes that favour inflation:

More generous post-pandemic safety-nets, or progressive taxes enacted to pay down large government debts, could redirect income towards freer spenders, creating inflationary pressure. Governments and central banks [may] prefer high economic growth and low unemployment to low and stable inflation.

You have been warned.

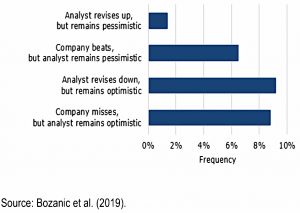

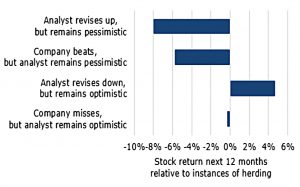

Contrarian analysts

Joachim Klement looked at a way in which sell-side analyst recommendations (which are typically useless for stock-picking) might be made useful.

- The trick is to follow analysts who don’t follow the herding instincts of the majority – what Joachim calls contrarian analysts.

When a company beats the forecast, most analysts report on this as a positive event and become more optimistic about the company’s prospects. Similarly, when an analyst increases her earnings forecasts it is generally accompanied by an optimistic assessment.

So negative contrarianism is when these events happen, but an analyst remains negative about the company’s prospects.

- And positive contrarianism is when there is an earnings miss or analyst downgrade, but the analyst remains positive about the stock.

One of these two events happens on average 12.5% of the time.

The study that Joachim quotes found that analysts who are more accurate and more experienced – and who work at smaller firms – are more likely to make contrarian calls.

As you can see, contrarian calls add value – other than a downgrade accompanied by optimism (which may be loyalty or wishful thinking).

Diversification

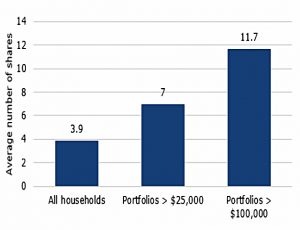

In a second article, Joachim looked at diversification.

The average number of stocks in a mid-1990s portfolio was four.

- Joachim says that internal data he has seen from private banks suggests that things have not improved.

It’s even worse than that, since the average of four means that most people have even fewer.

According to official statistics, 65.1% of trains in the UK arrive within one minute of their scheduled time.

The problem is that trains do not come in regular intervals. I am more likely to catch a train that has a bigger gap to the previous train [so] delayed trains have more passengers.

The later the train, the more passengers it carries. More and more people individually experience delayed trains.

With stock portfolios, the odd person with dozens of stocks will skew the averages.

- When a stock drops 10%, those with small (say 3-stock) portfolios take a 3% hit, whilst the guy with 50 stocks only loses 0.2%.

But more people experience the bigger hit, so the average impact is larger.

This can have serious implications when a company goes bust and the majority of its employees are invested in the company stock or when the housing market turns south all the while the majority of households have their wealth predominantly in their own home.

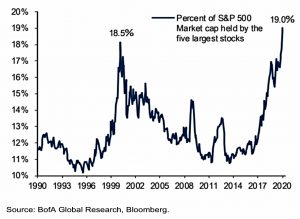

The increasing concentration of the S&P 500 means that even without Covid-19, conditions were ripe for a stock market decline to trigger a recession (as in 2000).

- A few stocks are likely widely held by the public in very concentrated portfolios.

Quick links

I have seven for you this week:

- The Economist looked at the future of the oil industry

- And claimed that the economic crisis will expose a decade of swindles and aggressive accounting

- And wondered how deep the downturns in rich countries would be

- Alpha Architect looked at what history has to tell us about the economic consequences of pandemics

- And asked whether there is a tail-risk premium in stocks

- UK Value Investor said that the S&P 500 is still expensive (as measured by its CAPE ratio)

- And Flirting with Models explained their tranching process in trend mandates.

Until next time.

Out of interest, I noted this morning from the March 2020 ONS Consumer Price Inflation report that “The consultation period for the UK Statistics Authority’s proposal to address the shortcomings of the RPI, originally scheduled to run until 22 April 2020, has been extended to 21 August 2020”