Dumb Alpha 2

Today’s post is our second visit to a series of old articles by Joachim Klement.

Carry

The fifth article in the series looks at the carry trade.

An investor borrows money in a currency with low interest rates, for example, the Swiss franc or the Japanese yen, and invests the proceeds in a currency with high interest rates, like the Australian or New Zealand dollar.

Investors benefit from the higher income but take on the risk that the high-interest currency will depreciate against the low-interest currency.

Carry has the same herding effect at momentum – as more people buy into the trade, demand for the high-interest currency rises, leading to its appreciation.

- And in the same way, when investors stop buying in, the trade can unwind quickly, and even crash.

Between 5 October and 9 October 1998, the US dollar suddenly depreciated against the yen by 13%, and the Australian dollar depreciated by about 10%. It was not triggered by any fundamental news about the countries.

You can also get fundamental triggers – in 2015 the Swiss National Bank removed its peg to the euro, resulting in an 18.8% shift which bankrupted lots of traders and a few FX firms.

Joachim recommends a tactic from Bekaert and Panayotov:

Instead of investing in carry trades with the most extreme interest rate differentials, one should invest in the less-crowded trades between currencies in the middle of the interest rate range.

This might mean borrowing euros or Swedish krona and investing in pounds or Norwegian krona.

- This will produce lower gains but less suffering in a crash, and hence higher risk-adjusted returns.

In other words, be less greedy.

Sell in May

Article number six looks at seasonal effects, of which the best known is Sell in May.

- The idea is that you spend the summer away from the stock market and buy back in November (or in some versions, as early as mid-September).

Many calendar effects do not survive increased scrutiny. The turn-of-the-month effect or the day-and-night effect require quite a lot of trading in a portfolio. If costs are high, many of these effects become unprofitable.

Others, like the January effect, disappeared once they were described in literature and exploited by professional investors.

Bouman and Jacobsen in 1998 found that Sell in May worked in 36 out of 37 countries, and is statistically significant in 20 of them.

- Even better, the two markets we are most interested in have very strong effects – the relative gain in the US is 11% and in the UK it’s a staggering 24%.

A follow-up from 2012 confirmed the effect, at an average of 10% over the 37 markets.

The effect does not come in lumps. It exists in three out of four years and does not depend on specific industries, countries, or months.

Hedge funds

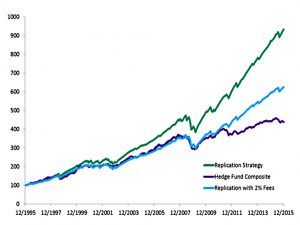

Article number seven looks at how to replicate a hedge fund strategy.

- Joachim would be fine about investing in the better hedge funds – if he knew how to select them – but he baulks at the 2 and 20 fee structure.

Hedge funds appear to be similar to all other forms of active management. If you can identify superior managers, you have a chance to reap superior performance or increased downside protection. But if you invest in the “average” hedge fund, you pay a lot of fees for underperforming a traditional portfolio.

So his plan is to invest in an average hedge fund, with lower fees (through replication).

- This should lead to above-average hedge fund returns.

There are two models:

- Jurek and Stafford say sell out-of-the-money puts and use a bit of leverage

- Ben Inker of GMO says sell at-the-money puts with no leverage.

At the beginning of each month, I sold a one-month put option on the S&P 500

index that was about 1% out of the money. I set the strike one tenth of the monthly volatility of the S&P 500. This way, the put option will be a little further out of the money if volatility is high, and a little bit closer if volatility is low.

The rest of the money goes into a one-month T-bill.

Pretty straightforward.

Earnings

Article number eight in the series looks at whether we should use trailing or forward earnings.

Value investing boils down to selecting stocks with the lowest price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio or lowest price-to-book (P/B) ratio.

Where PE is involved, lots of industry commentators use forward earnings, yet:

All the studies on the value factor have been conducted with trailing P/B and trailing P/E ratios, not forward P/E ratios.

So Joachim compared trailing PE to forward PE:

In the United States, the cheapest quintile of stocks based on trailing P/E outperformed the most expensive by 1.2% per year. When using forward P/E ratios, on the other hand, the most affordable stocks underperformed the priciest by 1% annually.

It’s not so bad in the UK:

Sorting stocks based on trailing P/E led to a 10.1% annual outperformance by the cheap stocks, while sorting based on forward P/E created a 7.4% outperformance.

But trailing PE is still better.

- This makes sense since analysts are not great at predicting future earnings.

Analysts are overly optimistic. Forward earnings are, on average, about 10% higher than subsequently realized earnings. However, this excess of optimism is not stable over time or across stocks.

So don’t use forward PEs.

That’s it for today.

- We’ve covered eight of the twelve articles, so I’ll be back with one more post in this series to look at the remaining four.

Until next time.