The Case Against Value

Today’s post looks at a series of articles from Validea Capital on whether value stocks will do as well in the future as they have in the past.

Validea

The three articles were written by Jack Forehand, who is Co-Founder and President at Validea Capital, and a CFA.

- Together with his business partner Justin Carbonneau, he runs a weekly podcast that is worth a listen.

The first of Jack’s articles was written back in 2018.

2018

Jack accepts the academic work in support of the historic outperformance of value stocks and is a fan of the strategy.

But he comes up with five reasons why it might not be as successful in the future as it was in the past:

- The world is different

- Central bank asset purchases encourage risk-taking without fundamental analysis

- Perhaps this will continue forever

- In this new world, value and quality don’t count for as much, and often don’t work

- Too many people are chasing value

- I think here Jack is focusing on smart beta funds

- He also mentions the tendency for factors to stop working once they are mentioned in the literature

- In the case of value, the Fama and French three-factor model would be the trigger

- The capital following value is more permanent

- Value investors need other investors to panic when value underperforms

- Permanent (passive) value investors reduce the effectiveness of the strategy

- This could even get worse as investors become better educated about the stupidity of panicking during downturns

- More computer power and data means more value traps

- More data and faster processing should mean more efficient markets

- This might in turn mean that cheap stocks are cheap for a reason

- By this Jack means a reason that doesn’t show up in the fundamentals, but in some other data – he gives satellite images of Walmart parking lots and credit card information as examples

- Value is a bet against technology

- Value strategies often make sector bets, and usually against tech

- Often value can be overweight sectors like financials

- Sometimes this is a good thing – like in 2000 (or possibly today, as tech starts to crash)

- One way of dealing with this is a sector-neutral approach (relative values within rather than between sectors)

Jack is not trying to say that value is dead, but instead, he’s trying to encourage investors to look for the other side of the argument:

No matter what style in investing you use, it is very easy to get caught up in a feedback loop that does nothing but support it. But by doing that you lose the ability to question yourself. You lose the ability to figure out how you might be wrong.

2020

Jack starts the second article by admitting that value has had a bad decade.

The problems were initially isolated to certain value metrics (i.e. Price/Book) and strategies that overweighted certain sectors, but in the past few years the damage spilled over. Just when it seemed things couldn’t get any worse, the coronavirus came in and dealt one more horrible gut punch.

But in the second half of 2020, value recovered a little:

Jack could feel optimism creeping in and wanted to check his previous assumptions.

He has a new list of problems for value, of which only the first is the same as in the previous article (though a couple of other rhyme):

- The Fed has changed the game

- A lower discount rate benefits longer-duration stocks, and value stocks are short duration

- Obviously, rates have risen since the article was written

- Value needs recessions and hasn’t been getting them

- Most of value’s excess returns come in and around recessions

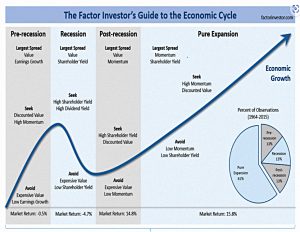

- The diagram below maps factor returns to the economic cycle

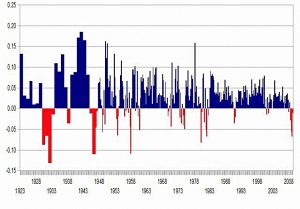

- We have also had fewer recessions (see the second chart)

- Value’s “intuitiveness” may be its downfall

- The more intuitive a factor is, the more investors will follow it

- More capital chasing it means lower excess returns (or none at all)

- This also ties back to Jack’s idea from the first article that fewer people are abandoning the strategy during underperformance – you need the weak hands to fold

- Passive investing may have broken the weighing machine

- Adding money to an index fund means buying the constituents at market cap weights, regardless of valuation

- This can mean that the largest stocks keep going up – the opposite of value

- Innovation could be leaving value behind

- Value investing is not only abet against tech, it is also a bet against innovation

- So if innovation dominates the economy (at the moment it seems that era might be over) then value has a problem

- Alternatively, less innovative firms could figure out how to take advantage of new technology, as has happened in previous tech waves

This diagram maps factor returns to the economic cycle.

Looking at US recessions (in red) since 1923, there have clearly been fewer and shorter ones in recent decades.

Jack ends the second article by noting that value has had another couple of bad years.

- But he still believes in value.

2022

In the third article, Jack reports that value is finally working and his confidence in it has risen.

He runs through the current status of five problems for value picked from the two previous lists:

- The Fed changed the game

- This one is weaker than before since both interest rates and inflation have risen

- Growth companies will struggle to generate immediate cashflows

- Too many value investors

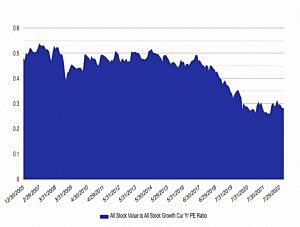

- The evidence for people abandoning growth and piling into value is weak (see the analysis below)

- Big data means value traps

- Jack can’t see how to measure the impact of alternative data on fundamental strategies, but he does think that investors should keep an eye on this issue

- Value is a bet against tech

- This headwind has now become a tailwind as tech values have fallen

- The problem could return, but through history, high-growth companies have underperformed the market

- A related issue is that traditional value strategies don’t handle intangible assets very well, which means that the value of tech firms can be overlooked – an adjustment to value measures would be welcome here

- A smoother economic cycle (fewer recessions)

- Jack now suspects that the absence of inflation allowed central banks to be more aggressive in controlling recessions

- Permanently high inflation could take this away, which would be good for value

- So we’ll have to wait and see just how persistent inflation ends up being

What would happen if the capital following value went up by 10x tomorrow and that change was generated by growth investors abandoning that strategy? The result would be buying pressure on value companies and a rise in their price and selling pressure on growth companies and a decline in theirs.

To check whether this is happening, Jack compares the PEs of growth and value stocks.

This is clearly not visible – the spread (ratio?) is in the 7th percentile of the data since 2006.

Conclusions

It’s an interesting series of articles, though without definitive conclusions.

- Economic conditions certainly support value more than when the first article was written, but we don’t know for how long they will persist.

There are no strategies that work all of the time, and value is just one example.

- Jack promises us another update in 2024.

Until next time.