Dumb Alpha 3

Today’s post is our third visit to a series of old articles by Joachim Klement.

Get rich slowly

The ninth article is about getting rich slowly, but it begins with a critique of the capital asset pricing model (CAPM).

CAPM predicts that stocks with higher systematic risk (i.e., higher beta) should have higher returns. Unfortunately empirical tests demonstrated that CAPM predictions are not valid in real life.

Indeed, low-vol stocks tend to outperform, though this just one of several anomalies.

In 1992, Fama and French published their seminal paper introducing the three factors of market beta, size, and value. Over time, a momentum factor, investment factor, and profitability factor were included.

Investment and profitability can be seen as elements of Quality. But back to low vol:

Instead of creating complex multilinear factor regressions, investors can outperform the market simply by selecting the stocks with the smoothest return profile — good, old, boring stocks that show no drama and a lot of stability.

This is good, because of the relationship between arithmetic (average) and geometric (compound) returns.

Geometric return = arithmetic return – 0.5 * variance. Thus, if volatility (or variance) declines, geometric returns increase for a given level of arithmetic return.

This means that for a given level of return, you should choose the investments with the lowest volatility in order to achieve a higher CAGR (and terminal wealth) in the end.

Just sit there

Article number ten is about when to change fund managers.

- Although it can make sense to buy stocks that have gone up (because of momentum), buying funds that have gone up is not a good idea.

But that doesn’t stop people from doing it.

Individual fund investors tend to buy funds that have had good performance relative to their peers and to sell funds with bad absolute performance.

Institutional investors with more resources might be expected to know better.

The problem is that while expert fund selectors have more tools at their disposal and spend more time analyzing funds, they are also under pressure to justify their fees and salaries.

It doesn’t sit too well with trustees if an adviser does all this work and then concludes that nothing needs to be changed — especially when a fund is underperforming.

So underperforming managers are fired.

Unfortunately, this is a bad idea:

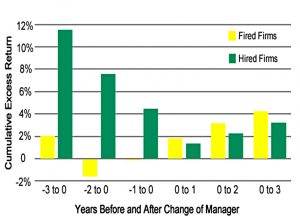

In the years before fund managers are fired, they underperform their benchmarks, while newly hired manager outperform their benchmarks by wide margins. Once managers have been fired and new ones hired, however, this outperformance disappears.

In fact, the fired managers on average tend to outperform newly hired managers in the three years after a change.

So it might make sense to buy the losers, what Joachim calls the “Dogs of Morningstar” strategy.

- Cornell, Hsu and Nanigan compared the performance of funds in the bottom decile of the Morningstar database over three years to those in the top decile.

In the subsequent three years, the funds in the bottom 10% outperformed the funds in the top 10% by more than 2%. Even the average funds outperformed the top decile funds.

If you can’t be bothered to implement this strategy, the best plan is to do nothing.

Instead of being motivated by the rule “Don’t just sit there, do something,” investors might instead act based on the rule “Don’t just do something, sit there.” Sticking to a selected fund for the long term — or just selecting funds at random — can be a significant source of alpha in the long run.

But as Joachim points out, this requires patience and discipline.

Do the right thing

Article number eleven is about behavioural tricks to help your investing. Joachim recommends:

- Not checking your portfolio value too frequently

- Not sticking to your asset class and sector allocation too closely

- Not watching financial news programmes

All of these things will tend to make you trade more frequently, and investors who trade more generally have lower returns.

Resisting that urge to adjust your portfolio becomes particularly difficult when you’re faced with losses. Loss aversion means you suffer losses more than you enjoy gains.

The best way to deal with this is to ignore your losses (by not looking at your portfolio value).

Assume an equity portfolio with a 10% annual return and volatility of 15%. The probability of a positive return over any given year is 93%. As a result, an investor who evaluates the portfolio once a year will experience a loss once every 10 years or so.

If the same portfolio is evaluated quarterly, a loss will occur about once every four quarters, or once a year. And if that portfolio is evaluated daily, roughly 120 days a year will register losses.

I think this can work both ways though – if you check your portfolio every day, you get used to the idea that it will be down on say 35%+ of the days, neutral on another 10% and up on 50%+ days.

- A down day won’t trigger you into selling, nor even 100 down days over the course of a year.

It’s like being a football fan – the top teams play 50+ games a season and they can expect to lose around ten of them.

- A single loss shouldn’t be a reason for panic.

I agree with not tracking allocations too closely.

- I see my target allocation as a destination which tells me which way to head in whenever I make a change to the portfolio.

I don’t have to be absolutely on track at all times.

I also agree that ignoring the vast majority of the financial press is a good idea.

The people working at Bubble TV and their counterparts at financial newspapers, investment newsletters, etc., are not in the business of providing good advice.

They are in the business of selling airtime, newspapers, and newsletters. And the best way to attract attention is to appeal to the emotions and instincts of their viewers and readers.

Which means sensationalism and exaggeration.

Stop losses

The final article in the series is about how Joachim came to love the use of stop losses, which began when he became involved in managing client money.

Not even sophisticated investors can handle long periods of negative performance or underperformance relative to a benchmark. When markets declined significantly, they all worried about their portfolio losses.

Worries turned into complaints, and if the losses grew too big or weren’t recovered fast enough, those complaints turned into asset outflows.

Joachim doesn’t believe that stop-losses necessarily enhance returns.

It all depends on the stop-loss rule used, the asset class, and whether there’s a bear or bull market.

But they do reduce drawdowns (and hence volatility).

For Joachim, stop-losses are all about client well-being and preventing people from selling out of a good long-term fund.

He also notes another advantage: during a cooling-off period after the stop-loss has been triggered, the sold investment can be re-assessed without the harmful influence of the endowment effect (where we prefer things that we already own).

- If the fundamental case still holds, we can re-enter when momentum turns positive once again (or when an inverse stop-loss has been triggered).

I only use stop-losses on the trend/momentum parts of my portfolio, where the long right tails provide the performance, and the long left tails are to be avoided.

- They are also an important part of risk management and capital preservation for strategies that involve a lot of trades.

And that’s it – we’ve been through all twelve articles.

- I hope you enjoyed our whistle-stop tour and picked up some simple tips on how to improve the performance of your portfolio.

Until next time.