Income and taxes

This is the third post in our series on basic personal finances, and looks and income and taxes.

So far we’ve talked about life stages, and how to plan for the future. Then we looked at personal financial statements (income statement and balance sheet) and how to analyse them with ratios.

Today we’re going look at the income side of the equation, and at how income is taxed in the UK. But first we need to discuss the difference between assets and income.

Income vs wealth

Many people think that income and wealth are the same thing, but they aren’t. The best way to think about this is the way that we made a distinction between the income statement and the balance sheet:

- Income is what happens this year (and shows up on the income statement)

- Wealth is everything that has already happened (and shows up on the balance sheet)

Income is a flow of money (a salary, or benefits, or dividends from shares), whereas wealth is a collection of assets owned and valued at a particular point in time.

Assets are normally split between physical (real) assets such as property, jewellery and art and financial assets (cash deposits, shares etc).

Taxes on Income

Like most people, I don’t like taxes. But again like most people, I have to pay them anyway. The UK tax system is famously long and complicated and has grown up through hundreds of piecemeal revisions, rather than a regular top-down re-design.

But in practical terms for most people it is quite simple. Unlike the US system for example, we don’t have to provide information on the dozens of deductions we are claiming, because we don’t have many deductions to claim. ((If you are self-employed, or operate through a limited company, things are more complicated))

Taxes (of all kinds) are important because they affect real-world decision-making. Before deciding whether to go for that new job, or ask for a pay rise, you need to know how much difference it will make.

Not what the number on your contract looks like, but how much cash will you have in your pocket. I will resist the temptation to describe an idealised tax system and instead will focus on things as they are. ((We have an election in three months’ time so they may not be this way for much longer))

There are two basic taxes on income in the UK:

- Income Tax

- National Insurance Contributions (NIC) on earned income (salaries from work)

For those on the lowest incomes, there is a third factor of benefit payments and in particular Tax Credits, both of which operate as a negative tax on income.

There are also transactional taxes which are paid as you spend money – VAT and stamp duty. VAT is considerable and acts as and additional tax on the spending power of income, but it’s hidden inside prices and is applied so remotely from the source of the funds that few people see it this way.

Tax is normally collected via the employer and for most people there is no more paperwork to complete. For high earners, or those with complicated tax affairs an annual “Self-Assessment” return must be filled in.

This can be done quite easily online using little more than a P60 from your employer and a few bank statements. If you owe more tax as a result, this becomes due at the end of the January following your April tax-year close.

Income tax can be reclaimed on investment products like pensions, VCTs and EIS, but NICs are not reclaimable. ISAs and SIPPs are outside the tax system and do not need to be declared in tax returns. ((Gambling and spread-betting profits are also non-taxable))

Income Tax

Income tax is usually collected by employers through `pay as you earn’ (PAYE). The amount due is calculated according to your income during the Tax Year, which runs from April 6th to April 5th.

Income tax is “progressive” – rich people pay proportionately more – and this is effected through a series of tax bands:

- the first £10,000 is tax free (the “Personal Allowance”)

- the next £31,865 (up to £41,865 total) is taxed at 20%

- from here to £150,000 of taxable income, the rate is 40%

- above £150,000, the rate becomes 45%

There is an added complication that the personal allowance is gradually withdrawn once income passes £100,000.

National Insurance

National Insurance was originally intended to fund pensions, unemployment and sickness benefits, but the money is not separated for these functions, and NICs are now better regarded as a supplementary income tax.

As with Income Tax, NICs are collected by employers. There is a series of bands, but this time they are regressive – the rates decrease at higher income:

- the first £7,956 is not taxed

- the income between here and £41,860 ((Close to, but annoyingly not the same as the £41,865 threshold for higher rate income tax)) is taxed at 12%

- any income above this level is taxed at 2%

The bands above refer to the employee NICs; there is a parallel system for employer contributions that we need not worry about here.

Example calculations

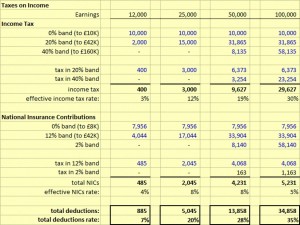

Here are the taxes levied on a range of incomes: £12K (roughly the minimum wage), £25K (roughly the average wage), £50K and £100K. You can see that percentage deductions rise with income: from 7% at the bottom, through 20% and 28%, to 35% at the top.

The smaller and regressive NIC blunts the effect of the progressive income tax. Below £42K the marginal combined rate is 32% (20% + 12%) but above £42K the combined rate is 42% (40% + 2%). This increase is less than a third, rather than the doubling that the income tax system suggests (40% vs 20%).

That’s all we have on income taxes. I’ll be back next time with more on expenses and budgeting.

Until next time.