Market Timing

Today’s post is the first in a series about Market Timing.

Contents

Objectives

In future posts, I’ll look at popular approaches for determining whether an investor should be overweight or underweight (relative to some neutral position yet to be defined) in a particular asset.

- Under the efficient markets theory this is clearly impossible, but I hope you will agree that the EMH clearly doesn’t apply to the world we live in.

- If you do believe in a strict form of the EMH, you can probably stop reading now.

Many discussions around market timing limit themselves to a comparison of timing the stock market vs a buy and hold strategy.

- Most private investors are bad at market timing, and underperform even the funds they are invested in (let alone the relevant index), so buy-and-hold does well here.

- It’s the same approach used to demonstrate that active funds must in aggregate underperform passive ones, since their fees are higher.

Our scope is wider than that – the end goal of the series is a set of indicators than can be used as inputs to a trading system based around continuous weightings to many asset classes and geographies.

- This would allow market signals to be integrated with stock-specific signals (such as price momentum from technical analysis).

In the medium term, I would be happy with a dashboard (a set of traffic lights or charts) that indicates the currently prevailing market conditions on a single screen.

But today I simply want to cover the major concepts involved in market timing, and how it fits in with the other key principles of investing.

Market timing

The essential division between investment schools is that between market timers and buy-and-hold investors.

- This is often presented as a division between active and passive investors, but as I’ll show in the next section, things are a little more complicated than that.

Market timing requires the processing of signals, and so is made more popular by the availability of data and of cheap computing power to analyse it.

- On the implementation side, the availability of low-cost ETFs which allow the private investor to access diverse asset classes encourages the consideration of market timing strategies.

Many of the techniques underlying market timing signals will be derived from technical analysis, and so the prevailing fashionability (or otherwise) of TA will influence the popularity of of TA.

Passive vs Active

The only true passive portfolio is one that can be left alone forever.

This is less than ideal for three reasons:

- The majority of investors are either in accumulation (adding funds to their pot) or decumulation (withdrawing cash).

- Static portfolios tend to be temporary.

- Many financial assets or proxies (such as art) are unavailable to private investors at reasonable levels of cost and liquidity.

- Complete Passivity implies and acceptance of market-cap weighting, which has been shown to be inferior to many other forms of indexing.

So we are all active investors – it is just a matter of degree.

From passive to active

The closest an investor will come to a passive strategy is monthly allocations to index tracker funds.

- The portfolio could be market cap weighted, or optimised for volatility (max SR), or use caps to low volatility assets (bonds and cash) in order to target a minimum return.

But even this approach requires choices about which indices to track, how many funds to use, and considerations of home bias (to the UK) and “away bias” (to dominant markets like the US).

- Plus there is the issue of periodic rebalancing to consider.

And what is suitable for accumulation will not be suitable for decumulation, so at least a temporary period of active management will be required during the switchover.

One step up from index funds are factor funds or smart beta.

- These funds passively track indices that are not defined by market cap.

- Popular flavours include momentum/trend, size, value/yield/carry, low volatility, equal weight and quality (stock fundamentals).

At the next level, investors will make use of actively-managed funds.

At the final level, investors will personally allocate to assets and geographies (and stocks) based on their predictions of future returns.

Variations

This fourth level is what we call market timing, and could include fundamental and technical approaches to individual stock selection (fundamental and technical analysis, and stock screeners).

- We’ll exclude stock selection and focus only on under- and overweighting of asset classes and geographies.

Sector rotation (eg. through the business cycle) will be treated separately and excluded from this series of articles.

- Rotation between asset classes will be included here.

The two main variations within market timing are:

- Pure market timers, who are either in or out of a market, and

- Dynamic asset allocators, who adjust weightings on continuous basis in response to market conditions.

Our end goal is the second approach, but it may be necessary to adopt a pure method as an early stage in implementation.

The other key division is the distinction between technical analysis (which I will take to mean the use of only price and volume information) and the use of fundamental and macroeconomic data.

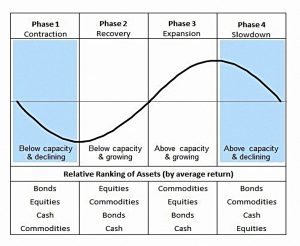

The business cycle

The theory underlying market timing is that the changing attitudes and behaviours of investors through the business cycle leads to trends in asset prices.

- Investor behaviour is assumed to be consistent between cycles, but this only gets us so far because cycles vary in shape and length.

The goal is to identify turning points, but there is no “magic bullet”, and multiple indicators will be required.

- “Confirmation” of changes from several sources is what market timers look for.

Types of signal

Popular signals include:

- Price (of an index)

- Volume

- New highs and lows (usually over the past year)

- Number of advancing vs declining stocks in a market

- Valuations (PE, price to book, dividend yields, or of the market to GDP)

- Interest rates

- Money supply

- Sentiment measures (consumer or business confidence, option purchases etc.)

Methodologies

Observers have identified seven approaches, though we won’t be using all of them:

- trend-following

- overextension / mean reversion

- fundamental analysis / forecasting

- seasonality

- There’s decent evidence for seasonal effects over the long-term, though many believe that they are too well known to work any more.

- In any case, at the market timing level, seasonality boils down to deciding whether to implement some level of extra allocation (particularly to stocks) during the summer months.

- cycles

- This approach includes things like Elliot Wave Theory, which we won’t be looking at further.

- pattern recognition

- This involves things like head and shoulders patterns, and we won’t consider this further.

- artificial intelligence

- AI is out of scope for this series of posts, other than the extent to which any automated asset allocation system is a form of expert system.

So we have three approaches to look at in more detail.

Trend following

We’re already familiar with this spin on momentum investing.

- Momentum factor funds are available here in the UK, but the CTA specialists seen in the US don’t exist (for private investors at least).

Trend uses lagging signals, which leads to some underperformance but a high degree of confidence in the method.

- Trend won’t work in sideways markets, where it is vulnerable to whipsaws.

The other big thing to note about trend following is that the goal is not outperformance per se (though it can be used for this in a trading system, perhaps with leverage).

- The goal is to avoid major drawdowns, and so reduce volatility.

Mean reversion

When applied to the long-term, this approach takes the form of signals like the CAPE Shiller index.

- Unfortunately, markets can remain overextended for long periods and indicators like the CAPE have limited short-term predictive ability.

In the short term, this approach takes the form of overbought / oversold oscillators.

- Fixed bands of standard deviations around price (like Bollinger bands) or percentage bands around moving averages of the price can also be used.

- Here the price will be expected to bounce of the edges of the envelope.

This approach works well in sideways markets and poorly during long trends.

Forecasting

Forecasting generates leading signals by comparing markets to other investments (stocks to bonds or interest rates) or to the economic cycle.

- We can also use sentiment indicators here.

With stocks, values (prices) will be assumed to follow the future direction of earnings and dividends.

Forecasts can be hard to implement since the signals are often months early, even when a leading indicator like the stock market itself is used.

Conclusions

I hope we’re now clear on what is and isn’t market timing, as far as this series of articles is concerned.

Market timing is bound to involve more asset reallocation and trading than a passive approach.

- This exposes market timers to the risk of higher costs and potentially tax charges.

It also requires more time to implement and administer.

Against this, market timing offers a good shot at reducing volatility, and under certain circumstances, of enhancing returns.

There are three approaches that we are interested in, and one in particular.

Trend following and mean reversion from price and volume data will be used in our investment database / trading system, and are often discussed in our articles which look at trading books and technical analysis.

- So while we will note which of these techniques are most useful and how they are used, our focus will be on forecasting using market, macroeconomic and sentiment signals.

In the subsequent article we’ll look at how someone more experience than me in this area has approached the problem – at this stage I’m not sure who this will be.

- Until next time.