Pension Deficits 4 – The Story In Pictures

Today’s post is the fourth in what was planned to be a three-part series about Pension Deficits.

Contents

The never-ending series

This was originally intended to be a 3-part series on company pension deficits, but events have intervened.

- First, we had the “Milking and Dumping” report that we covered a couple of weeks ago, and then the FT ran a series of articles focused particularly on government pension deficits.

Pensions deficits are obviously a hot topic.

- So bear with me while we extend the series of articles to five, and look today at what the FT had to say.

- I should warn you that there are lots of graphs today, but a picture paints etc.

Low Yields, High Stress

The FT began in the US, with the attempt by the Central States Pension Fund (CSPF, for truckers) to cut benefits

- The attempt was blocked by the US Treasury.

- Without the cuts, the CSPF will run out of money in less than 10 years.

The FT expects such attempts to become common in the future.

- Indeed, here in the UK we’ve just had a similar attempt to reduce benefits to the Tata Steel workers in order to make the sale of the plant more attractive.

Unless they can sell the future liabilities to an insurance company (which is expensive when bond yields are low), the only way out for defined benefits (DB) plans is to default.

- This means bankruptcy in the US, and transfer to the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) in the UK.

- The PPF pays out 90% of future pensions, with a cap of around £34K annually.

In the US, Detroit’s pension scheme went bankrupt in 2014, resulting in a cut of 4.5% to pensions, plus the loss of indexation.

The problem

As we have already explained, there are two main problems:

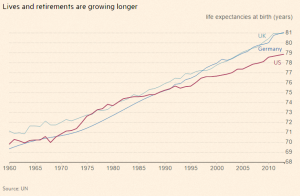

- People are living longer

- Returns on the assets that are used to measure pension liabilities are predicted to be lower

- This, in turn, has two parts: we have historically low interest rates,

- and we use the wrong assets to meet and measure liabilities

The demographics and returns push up the liabilities, which means that more money needs to be set aside by individuals and companies.

- This, in turn, defeats the object of low interest rates, which is to stimulate spending.

The demographics

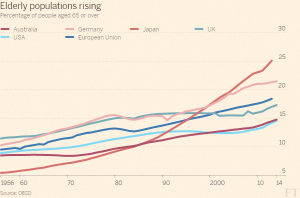

Here are a few graphs which are either depressing (in the context of pension liabilities and funding) or representative of an extraordinary human achievement (if you are interested in living a longer life).

Life expectancy in the UK has increased by more than 10 years during my lifetime, effectively saving me 20% of the time that I have been alive.

- This means that retirement has expanded from one decade to two.

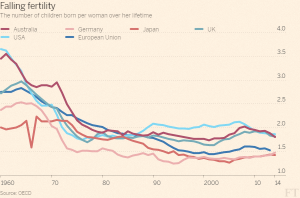

At the same time, people are having fewer children.

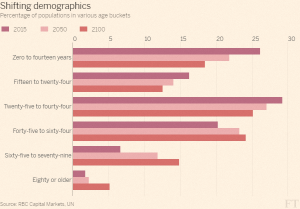

This means that the composition of society is changing.

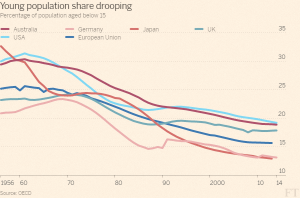

There are more old people (retirees).

And fewer young people (future workers).

And this is expected to continue.

All of these changes mean that the liabilities of most schemes have increased dramatically, and there are fewer and fewer people of working age (as a proportion of those retired) to fund the schemes.

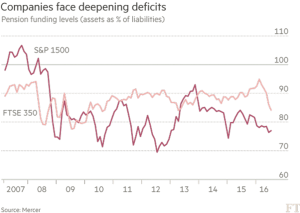

The wrong assets

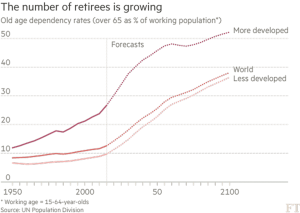

Pension funds are increasingly full of bonds rather than equities.

- The idea is that bond returns are more predictable, and so can be “matched” to pension fund liabilities (this is known as “liability-driven investing”).

But it’s a bad idea for several reasons:

- Stocks produce higher long-term returns than bonds, and pension funds are the quintessential long-term investor

- Bond returns are not so predictable, and we are at the end of a 30-year bull market in fixed income

- The purchase of more bonds by the pension funds has driven yields down (and prices up) even more, helping to inflate the bond bubble

- The pension fund’s liabilities have proved difficult to predict, and so are poor candidates for matching

It’s ironic to note that while pension funds were mostly invested in stocks, there were two serious market crashes (2000 and 2008/09).

- Pension fund trustees appear to be competing with private investors for the crown of “worst market timer”.

Poor returns

Adding to the problems of choosing the wrong assets are the diminishing returns upon them.

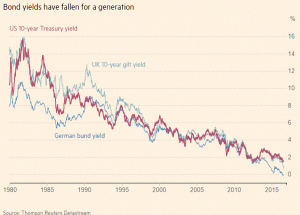

Bond yields have been falling since I became an adult more than 30 years ago (though we had a spike in the late 80s / early 90s here in the UK.

- It’s a result of the central bank focus on controlling inflation (which was admittedly a problem in the 1970s).

- This has meant that interest rates have steadily fallen, particularly since the 2008 financial crisis.

- The benchmark 10-year US Treasury yield has fallen from 16% in 1981 down to just 1.5%.

As well as coupons falling, the terms of bonds have been increasing, meaning that pension funds are locked into lower returns for longer.

The public sector

Perhaps the worst situation is in US public sector funds.

- Most pension funds use bond yields to discount their future liabilities

- With yields so low at present, this leads to high current liabilities

The public sector in the US is allowed to choose its own discount rate

- Officially this is the expected return on the pension fund’s investments

- In practice, numbers higher even than historic returns are used

These rates are far higher than current bond yields and higher than the true expected returns.

- They mean that current liabilities are massively underestimated, and deficits are much larger than those reported by the funds.

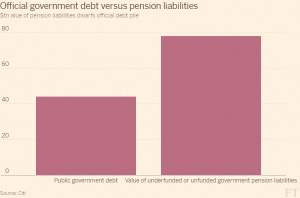

- A Stanford professor has estimated US public deficits to be $3.4 trn (compared with $562 bn for the S&P 500).

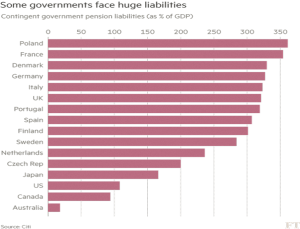

Many countries are in a similar situation, as they operate “pay as you go” pension schemes (today’s workers pay in to fund today’s pensioners).

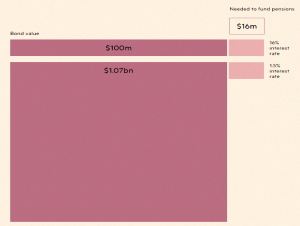

Bond maths

The 10-year US Treasury rate we met earlier is known as the “risk-free” rate – the return that you can get without taking any risk.

- This is a very important number in the financial system, used to price all kinds of things from pensions deficits to annuity rates.

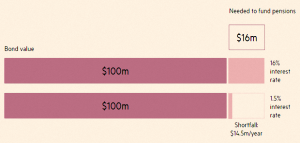

So back in 1982, with the rate at 16%, a pension fund could invest $100M in Treasuries and receive $16M annually.

- Now, with rates at 1.5%, they would only get $1.5M annually.

Looked at from the other direction, the fund would need to invest $1.1bn in order to receive the $16M that they received in 1982.

Solutions

Potential solutions include working longer, saving more, and lower pension payments (as well as changing the mix of assets in the pension funds).

- None of these is appealing to the current population, and by extension, to a government that wants to get re-elected.

It is possible that governments will relax the rules to allow pensions to invest in illiquid infrastructure schemes (transport, energy, networks etc).

But it’s also quite likely that we will continue to kick the can down the road until a crisis forces a change of direction.

For the individual investor, the key factors are:

- live within your means and save as much as you can each year

- keep costs and taxes to a minimum

- diversify your asset allocation, but keep the majority in assets that produce high returns over the long-term (stocks)

Conclusions

I don’t think we’ve covered too much new ground today, but all these FT graphs were just too useful to ignore.

I’ll be back in a couple of weeks with some UK case studies, and then we can wrap up the series with some conclusions.

Until next time.

Sources

- Low Yields, High Stress

- Pensions pain: disaster is avoidable

- Pensions and ageing populations: the problem explained

- Bond mathematics and the scale of pension deficits