Predictably Irrational 2 – Social Norms, Arousal, Procrastination and Ownership

Today’s post is our second visit to the book Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely.

Social Norms

Chapter 4 looks at why we are happy to do some things (that are expected of us socially) but which we would not do if we were paid for them.

- Dan starts with the hypothetical example of offering to pay for Thanksgiving dinner at your mother-in-law’s.

We live simultaneously in two different worlds–one where social norms prevail, and the other where market norms make the rules.

Social norms provide pleasure for both [the giver and receiver], and reciprocity is not immediately required. Market norms are sharp-edged: wages, prices, rents, interest, and costs-and-benefits. When social and market norms collide, trouble sets in.

It’s “you get what you pay for” versus “you get this for nothing”.

Sex is a good example of the two contrasting offers.

- Dan imagines a guy paying for the first three dates with a girl.

At this point, he’s hoping for at least a passionate kiss at the front door. On the fourth date he casually mentions how much this romance is costing him. Now he’s crossed the line. Violation! She calls him a beast and storms off.

The implication is that the girl is a prostitute.

Dan tested this effect by paying five dollars, or 50 cents, or nothing for people to drag circles across a computer screen for five minutes.

Those who received five dollars dragged on average 159 circles, and those who received 50 cents dragged on average 101 circles.

But the ones who were not paid dragged 168 circles.

There are many examples to show that people will work more for a cause than for cash.

Pro-bono lawyers are the example that Dan uses.

Next, Dan looked at gifts.

Surely your mother-in-law would accept a good bottle of wine at dinner. Or how about a housewarming present (such as an eco-friendly plant) for a friend?

He repeated the circle-dragging experiment with cheap and expensive chocolates as rewards (Snickers and Godiva).

- Now everyone dragged around the same number of circles.

No one is offended by a small gift, because even small gifts keep us in the social exchange world and away from market norms.

The third version of the experiment gave participants the chocolate but labelled it with a market value (fifty cents or $5).

- Now the cheap chocolate led to less work.

Participants reacted to the explicitly priced gift in exactly the way they reacted to cash, and the gift no longer invoked social norms.

Dan found the same result when asking passersby to help unload a sofa from a truck:

People are willing to work free, and they are willing to work for a reasonable wage, but offer them just a small payment and they will walk away. Gifts are also effective for sofas, but mention what the gift cost you, and you will see the back of them.

The next experiment Dan mentions involves word sorting (which could either be related to money, or not) followed by a disk arrangement puzzle.

Thinking about money made the participants in the “salary” group more self-reliant and less willing to ask for help.

But these participants were also less willing to help an experimenter enter data, less likely to assist another participant who seemed confused, and less likely to help a “stranger” (an experimenter in disguise) who “accidentally” spilled a box of pencils.

Market participants are selfish and self-reliant.

They wanted to spend more time alone; they were more likely to select tasks that required individual input rather than teamwork; and when they were deciding where they wanted to sit, they chose seats farther away from whomever they were told to work with.

Just thinking about money makes us behave as most economists believe we behave – and less like social animals.

The next experiment is the famous one (from Freakonomics) involving day-care centre fines.

- Parents would arrive late to collect their children, so fines were introduced.

This made more parents late – they felt they were paying to be allowed to choose for themselves whether they wanted to be late.

- When the fines were removed, even more people were late – now both the social and the market controls have been removed.

Social relationships are not easy to reestablish.

Dan notes that many companies now try to present themselves as social companions.

- With the rise of social media since the book was written, this trend has only intensified.

The idea is to increase loyalty and promote the tolerance of minor screw-ups.

- The problem is that when the customer screws up (eg. late payment) a market punishment (a fine) will destroy the social relationship, and often lead to public complaints from the “wronged” customer.

Something similar has also happened with employees.

- Work no longer stops at the factory gate – lots of us take it home with us.

This new contract may lead to, say, hard work around deadlines, but it also implies that when things are tough (they are sick, or the markets are bad), the company will support them.

- Wider trends towards short-termisim and cost-cutting make such support problematic.

Dan is US-based, so he focuses on the importance of medical benefits.

- He also notes the positive social culture at startups, which often retained when those companies grow into giants (Google, Apple).

Social norms are particularly relevant to (badly-paid) public services – police, firemen, soldiers and teachers (and here in the UK, the NHS).

Dan is against testing in schools, as it reinforces a market norm.

- He would like to see school curricula linked to social, technical and medical goals.

Not surprisingly (since he is an academic) his social goals are left of centre.

Dan is also a fan of the Burning Man festival, where “money is not accepted”.

- I suspect the festival has become more commercial since the book was written.

Dan’s argument that market norms destroy social norms is well-made.

- The question for me is whether modern societies could ever agree on a common set of social norms that would satisfy us all.

I think society is too fragmented for this, and social media brings out the worst in people.

- In particular, the politics of the last few years (including Brexit, anti-capitalist environmentalism and even the divided reactions to the Covid-19 response) make me think that we cannot all agree on anything.

And if we can’t, then I would rather interact with those who do not share my social norms on the basis of market norms.

- That way, we both still get something out of the deal.

Which is pretty much the way that money got started in the first place.

Arousal

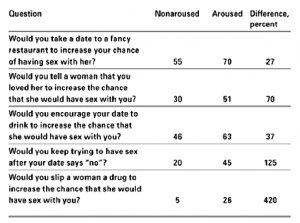

Chapter 5 is about how the effects or arousal are underestimated, and in particular, are not predicted by the people they affect.

- To study decision making under sexual arousal, (male, heterosexual) students were encouraged to masturbate to porn on a laptop, whilst simultaneously self-reporting their arousal levels and answering questions on the screen.

The yes/no questions asked whether subjects would be willing to participate in certain risky, niche and sometimes illegal sexual activities.

One set of questions asked about sexual preferences. A second set of questions asked about the likelihood of engaging in immoral behaviors. A third set of questions asked about [the] likelihood of engaging in behaviors related to unsafe sex.

In the initial session, subjects would imagine they were aroused, and answer some questions.

- In a subsequent session, the same subjects would actually become aroused, and answer some more questions.

When the participants were aroused they predicted that their desire to engage in a variety of somewhat odd sexual activities would be nearly twice as high as (72 percent higher than) they had predicted when they were cold.

The increased likelihood of engaging in immoral activities was even higher (though there was a much smaller increase in the willingness to forego safe sex).

Dan invokes Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde as an analogy, along with Macbeth, Oedipus Rex, and Freud’s id and superego.

- I’d like to throw the Tempest and its sci-fi skin Forbidden Planet in there as well.

The theory also fits well with Kahnmann’s work on Thinking Fast and Slow.

- The lesson is clear – save your decision making for the quiet times, not the heat of battle.

Procrastination

Chapter 6 looks at why we can’t make ourselves do what we want to do.

Dan starts by describing the collapse in the US savings rate, and the rise of consumerism, credit card debt and too much stuff.

- Dieting is a similar issue.

The failure of people to do what’s right is linked to the arousal problem from the previous chapter.

When we promise to save our money, we are in a cool state. When we promise to exercise and watch our diet, again we’re cool. But then the lava flow of hot emotion comes rushing in.

Dan decided to test this behaviour by letting students set their own deadlines for three papers due over a 12-week semester.

Once you set your deadlines, they can’t be changed. Late papers would be penalized at the rate of one percent off the grade for each day late.

Since there was no penalty for early submission, the obvious answer would be to choose the end of the term for all three papers.

- But that requires the willpower to spread your work evenly through the term.

A second class was told merely that all papers needed to be handed in at the end of the term.

- And a third class was allocated deadlines in the fourth, eighth and twelfth weeks.

Students in the class with the three firm deadlines got the best grades; the class in which I set no deadlines at all had the worst grades, and the class which were allowed to choose their own three deadlines finished in the middle.

So students procrastinate (no surprise) and curtailing their freedom is the best fix.

- Dan seems equally impressed that letting them choose deadlines had a positive effect (relative to no deadlines, not to imposed deadlines).

Resisting temptation and instilling self-control are general human goals, and repeatedly failing to achieve them is a source of much of our misery.

This is certainly the case for investment.

- You need to think long term, and to pay yourself first.

We have previously discussed the marshmallow test as a predictor of success in life, including investment.

Dan has some specific observations on saving.

- My own preference is for mandatory retirement saving, as used in Australia.

He mentions the trick of keeping a credit card in an ice-block in the freezer, which needs to be thawed to be used.

- Online spending with card details stored in browsers would get you around this one.

He also talks about the public self-shaming of bloggers who are in debt.

Dan would like to see a credit card which would allow people to restrict their own spending behaviour.

Users could decide in advance how much money they wanted to spend in each category, in every store, and in every time frame.

Cardholders would also choose their own penalty for failure – perhaps a fine transferred to locked-up savings, or to a friend or a charity.

- Dan even pitched such a card to a US bank – they didn’t call back.

Perhaps FinTech can provide such a product, but I wouldn’t hold your breath.

Ownership

Chapter 7 is about why we overvalue what we have – the endowment effect and loss aversion.

We fall in love with what we already have. We focus on what we may lose, rather than what we may gain. [And] we assume other people will see [a] transaction from the same perspective as we do.

Dan starts with his university basketball team, which is too popular for its small stadium.

- Tickets to the games (which are also televised) are allocated via a tent queuing system where a member of each tent must respond to the random blowing of an air horn, or else his tent will be sent to the back of the queue.

In the last 48 hours before a game, each member of the tent has to respond to the horn, rather than just one of them.

- And for really popular games, those at the front of the queue only get a lottery number – a chance of a ticket rather than an actual ticket.

It’s safe to say that had I attended Duke University, I would have seen no basketball, other than on TV in a bar.

Dan wondered whether the students who won tickets would value them more than those who queued and lost.

- So he and a colleague tried to buy the tickets and to sell them on.

The students who did not own a ticket were willing to pay around $170 for one. Those who owned a ticket, on the other hand, demanded about $2,400 for it.

Buyers compared the transaction to alternate uses for the money, but sellers stressed the experience and the lifelong memories.

- There was no market price for these tickets.

Dan also notes that:

The more work you put into something, the more ownership you begin to feel for it.

This even applies to IKEA self-assembly furniture.

We can begin to feel ownership even before we own something.

This applies to eBay auctions (and auctions in general).

- It also explains how advertising works.

Trial periods for premium services and money-back guarantees also exploit this weakness.

And ownership applies to views as well as objects.

- Confronted with evidence against their views, many people will “double-down” even harder.

Conclusion

That’s it for today.

- We’re halfway through the book, so there will be another two articles in this series, plus a summary.

Until next time.